- In our joint investigation with Mongabay and BBC News, we built a database of public reports to shed light on a widespread problem for which there was limited data.

- The database enabled us to target field reporting, identify trends and connect plantation companies to major consumer goods firms. Now, we are making it public for others to use.

- This article sets out how we developed the database, how we used it, what it includes, and its limitations.

In Sumatra, villagers occupied an oil palm plantation and set tyres on fire; in the Bangka Belitung islands, they filled the local parliament building demanding action; in Borneo, paramilitary police were deployed to control their protests.

Each of these incidents appeared in local media reports in Indonesia in the past few years and told what was becoming - to anyone paying attention - an increasingly familiar story.

Since the 1970s, as corporate-run palm oil plantations spread across Indonesia, companies promised to share them with local villagers, in plots known as “plasma”. Initially, they made these commitments to secure access to land and subsidised government financing; from 2007, it was a legal obligation to share a fifth of any new plantation with villagers.

During our field reporting in Indonesia’s palm oil heartlands, we repeatedly encountered allegations that companies were failing to deliver. Local media reports from Sulawesi to Sumatra told a similar story, with a steady stream of appeals to government, protests, direct action and sometimes even violence, due to simmering conflicts over plasma.

When we began to investigate this in earnest, one of the key questions we sought to answer was just how widespread this problem was. It soon became clear that government monitoring was patchy and unreliable. Government agencies themselves openly acknowledged the flaws in their data. Most palm oil producers declined to share data that would enable us to interrogate their claims that they were complying with the law.

As it became apparent that there was no definitive, reliable dataset, the potential utility of the local media reports grew into sharper relief. We began to compile them into a database, comprising every public report we could find of a plasma-related dispute. As well as local news stories, the database incorporated reports by credible nonprofits, government agencies and national publications.

To allow us to analyse how trends in conflicts over plasma were shifting over time, we included allegations made between January 2012 and May 2022, when the results of our investigation were first published. We excluded any cases where the nature of the allegation was unclear; the identity of the company facing the allegation was unclear; there was evidence the problem had been resolved; or we felt the article was of insufficient quality to merit inclusion. The dataset ultimately expanded to more than 200 individual cases.

While we eventually sent reporters to 27 cases to investigate them in greater depth, it was beyond the scope of our investigation to verify all of the allegations in the database. The data complemented, rather than replaced, the shoe-leather reporting that formed the foundation of our investigation.

Coding the cases by date, location, the company involved and various other typologies gave us insights into broader trends. We could see where allegations were occurring; where cases were escalating into protests; and which corporations were facing particularly high numbers of allegations.

Using the data from public reports to generate insights

The database helped us to identify two main categories of allegation that were being levelled at companies. First, that companies had allegedly promised plasma, or were legally required to provide it, but had never done so. Second, that the plasma did exist, but communities were receiving inadequate profits from it (see this post for a more detailed explanation of this second category). We also used the dataset to target our field reporting, conduct additional analysis and present our findings visually.

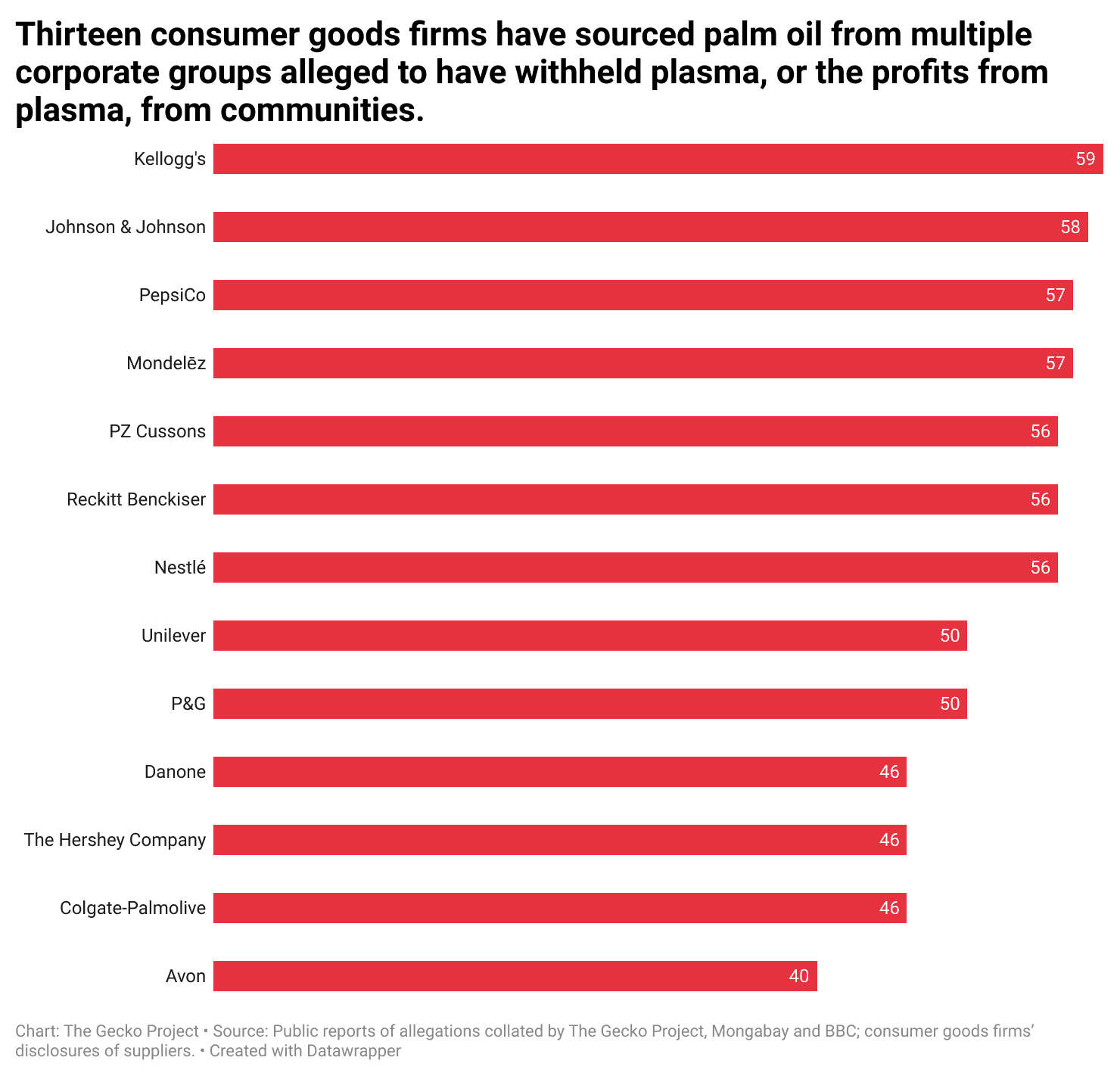

By categorising and analysing the alleged problems, our reporting team - including Mongabay and BBC News - produced graphics setting out the scale of the problem across Indonesia.

We identified where and when people had protested or taken direct action against companies to map these incidents out across Indonesia and over time.

We cross-referenced cases in our database against data published by consumer goods firms on the source of their palm oil, to identify the number of their suppliers that were implicated in plasma conflicts.

We presented a summary of our findings to the palm oil buyers named in our investigation, highlighting their supply chain connections to specific cases we had examined in depth, and to the larger number of cases in the database.

In response, the buyers pointed to their existing policies aimed at protecting human rights and eliminating "exploitation" from their supply chains. Some noted that they required their suppliers to comply with the law. They said they engage with their suppliers when potential violations of these policies are brought to their attention, and would do so for the cases identified in our article.

Four companies committed to broader efforts to determine and mitigate their exposure to problems with plasma.

The database has limitations. It includes allegations that have not been independently substantiated. As it seeks to incorporate allegations made over a period of multiple years, it may include conflicts that have since been resolved. On the other hand, it likely substantially underestimates the true number of conflicts over plasma, as it only captures those that have caught the attention of reporters, researchers or government agencies.

Nonetheless, it provided valuable insights into broader trends for our investigation, and can also serve as a starting point for further investigation, research and action by others.

Categorising the data

This section sets out those fields in the dataset that we’re making publicly available. We categorised the data from the reports using the following headings:

- Company Name: The name of the plantation company referenced in the public report(s).

- Parent Company: The name of the parent company that, according to publicly available data, owned the plantation company as of May 2022; this field is listed as "Unknown" if we were unable to identify the company’s owner.

- Province: The province in which the company subject to an allegation was operating, according to public reports.

- District: The district (kabupaten in Indonesian) in which the company subject to an allegation was operating, according to public reports.

- Sub-district: The sub-district (kecamatan in Indonesian) in which the company subject to an allegation was operating, according to public reports. This field is left blank if the sub-district was not named in public reporting. When an allegation referred to a plantation company that was operating in more than one sub-district, both are listed.

- Village: The name of the village affected by the allegation, according to public reports; this field is left blank if the village was not named in public reporting.

- Date of most recent report: The date on which the most recent public document relating to the allegations was published. (Note: the dataset also includes public reports published before this date.)

- Allegations that companies have failed to provide plasma: Allegation(s) by community members, government officials, civil society organisations or researchers that a company has either failed to provide some or all of the plasma it is legally obligated to, or failed to provide all or some of the plasma that it promised to provide.

- Allegations that communities are receiving inadequate payments from plasma: Allegation(s) by community members, government officials, civil society organisations or researchers that a company managing a plasma scheme has failed to make adequate payments to members of the community involved in that scheme. This form of plasma dispute was the subject of our second major story based on our plasma investigation. For a summary of our findings and to gain a better understanding of the allegation, see this article.

- Protests: Instances where community members have staged a public protest or carried out direct action as a collective display of grievance with a company because it has allegedly failed to provide plasma or made inadequate payments to community members.

- Government intervention: Cases where, according to public reports, government officials at any level have intervened in a plasma-related dispute between a community and a company. This includes stating publicly that they will take action; holding public hearings; mediating between communities and companies; conducting field visits to verify allegations; and/or sanctioning the company.

- Source: Hyperlinks to the public reports in which the allegations related to plasma have been published.

We stopped updating the database at the end of 2022, and are no longer adding new reports.

We are releasing the dataset under the Creative Commons CC BY-NC licence. Browse the data above or download it here. If you have any questions or comments, contact info@thegeckoproject.org.