Multiple consumer goods companies have suspended sourcing from the palm oil producer First Resources in the wake of an investigation by The Gecko Project. But others are facing criticism for failing to deal with evidence of deforestation in their supply chains by delegating responsibility to their suppliers or an industry certification scheme.

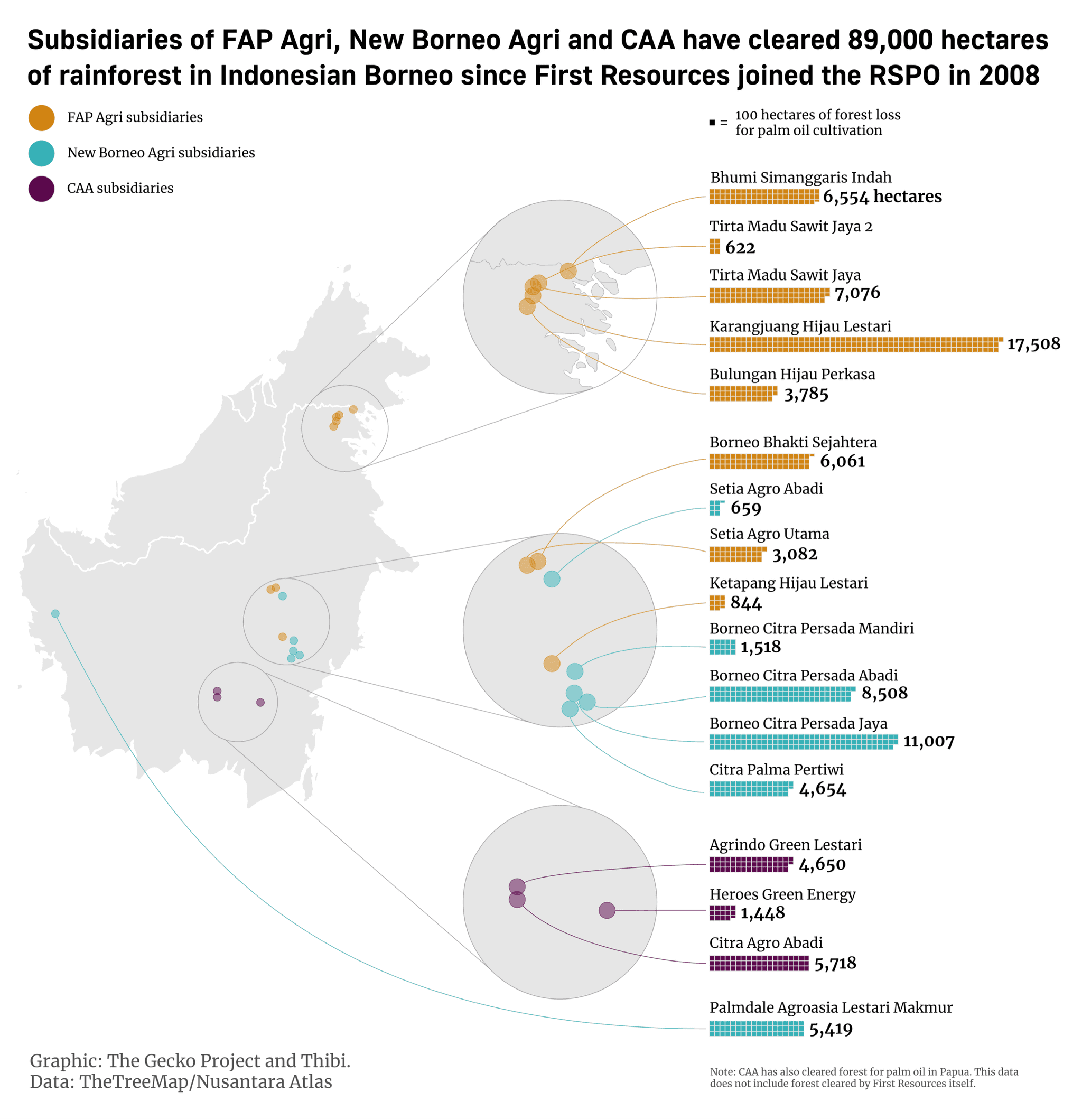

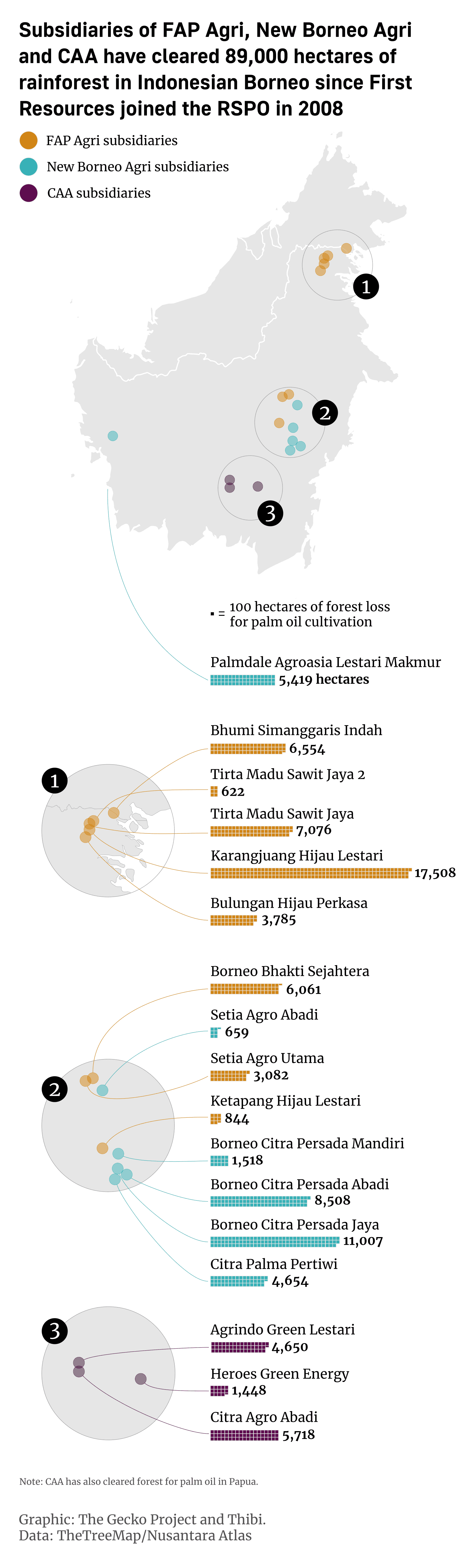

First Resources, a Singapore-listed palm oil producer, made a public commitment to keep forests standing in 2015. But The Gecko Project’s investigation, published last November as part of a collaboration with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, found evidence suggesting that First Resources has secretly controlled a network of “shadow” companies that have cleared tens of thousands of hectares of Indonesian rainforest.

In interviews with The Gecko Project, former employees said that First Resources had shared senior management, staff and even an IT system with two other corporate groups, FAP Agri and New Borneo Agri. Two First Resources employees, documents show, were even named as legal representatives of New Borneo Agri.

Responding to the investigation, First Resources said that New Borneo Agri and another group of alleged “shadow” companies, Ciliandry Anky Abadi, were neither its “subsidiaries, associated companies, nor related parties”. It reiterated earlier statements that it had no control over FAP Agri.

What is a shadow company?

Many of the corporations that dominate the palm oil and forestry sectors in Indonesia are publicly-listed companies that publish lists of their subsidiaries. But some also allegedly control companies that they do not admit to owning. These have become known as "shadow companies".The real - or "beneficial" - owners of shadow companies are often difficult to identify. In some cases, the companies have layers of shareholdings ending in a secrecy jurisdiction, where information about their ownership is not publicly available. In other cases, shadow companies use nominee shareholders, who act as fronts for the real owners.

Some major corporations that have made public "zero deforestation" pledges and claim to operate sustainably also allegedly operate shadow companies that are clearing rainforests. A 2024 analysis by The Gecko Project showed that the companies that have cleared the most rainforest in Indonesia in recent years are all registered in secrecy jurisdictions, and are alleged to be shadow companies of corporations that present themselves as "sustainable".

First Resources’ statement has failed to reassure some companies that have sourced palm oil from the corporation. The skincare firm Beiersdorf, which produces Nivea moisturiser, said that it was “deeply concerned” by the findings and was “taking as much action as possible.” It stressed the difficulty of getting multiple suppliers in its “long and complex” supply chain to suspend First Resources, but stated that two had done so at its request.

The Gecko Project asked 16 consumer goods firms and palm oil processors that have recently sourced from First Resources what steps they had taken in response to the investigation. Half said that they had suspended First Resources, including Beiersdorf, cleaning and personal care company Procter & Gamble, food manufacturers FrieslandCampina, Danone and Vandemoortele, laundry and hair care company Henkel, vegetable oils firm Lipsa and chemicals company BASF.

“It's good to see that companies have responded with suspensions,” said Gemma Tillack, forest policy director at the nonprofit Rainforest Action Network, or RAN. “It is critical that we see immediate action in cases where shadow companies are involved in deforestation, so the investigation is setting an important precedent for the palm oil sector.”

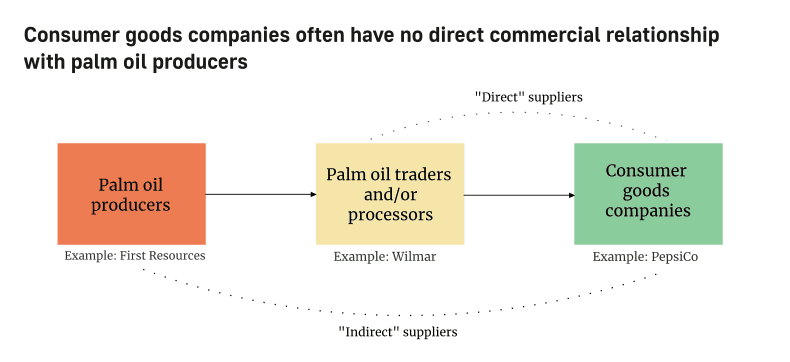

But other companies have not - for now - ruled out sourcing palm oil from First Resources. The remaining consumer goods firms that responded to our questions said they were instead contacting the companies from which they buy palm oil directly, typically describing the process as “engagement”. These companies, in turn, buy from First Resources.

The Belgian chocolate maker Barry Callebaut said that “engagement” involved asking its direct suppliers what they had done to investigate the allegations or “remediate” them, while chemicals firm Oleon said its direct suppliers sent monthly updates “on the progress First Resources is making.” But some other consumer goods firms that described themselves as “engaging” declined to provide details of what this process involved, or which direct suppliers they were speaking to.

Several consumer goods firms said that it was difficult for them to act quickly because of the complexity of their supply chains and the absence of a direct relationship between them and First Resources. “While we request timely action, the timeline of the investigation is stipulated by our suppliers' grievance processes,” said Sara Thallner, Barry Callebaut’s head of corporate communications.

| Suspended First Resources | Engaging with suppliers | No response |

| BASF | Barry Callebaut | Grupo Bimbo |

| Beiersdorf | Colgate-Palmolive | |

| Danone | PepsiCo | |

| FrieslandCampina | PZ Cussons | |

| Henkel | Upfield | |

| Lipsa | Oleon | |

| Procter & Gamble (P&G) | AAK | |

| Vandemoortele |

By contrast, a smaller number of commodity traders that supply these consumer goods firms do have a direct commercial relationship with First Resources. The Gecko Project contacted six of these traders to find out how they had responded to the investigation. One, Cargill, said that it had started its own investigation that included a “thorough review” of First Resources’ statements and meeting with the company.

The others that responded, however, stated only that they were waiting for the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, an industry body known as the RSPO, to rule on a formal allegation submitted to its complaints system that First Resources controls FAP Agri and CAA.

| Name of trader | Statement |

| ADM | No response. |

| Bunge | “We are following the RSPO complaint process and will respect the final decision made.” |

| Cargill | “We take The Gecko Project’s allegations very seriously and immediately initiated an investigation into their validity… Any decision regarding our ongoing relationship with FR will be based upon their clear and sustained response to our concerns.” |

| Louis Dreyfus Company | “LDC will continue to monitor the progress of the RSPO investigation.” |

| Musim Mas | “The FR issue is being addressed through RSPO Complaint System, we will monitor the progress.” |

| Wilmar | “We remain reliant on the RSPO Complaints Panel to complete its investigation and present its findings once ready.” |

The RSPO, however, has already spent three years considering this complaint, without coming to a conclusion. It is only now commissioning an independent investigator to examine the allegations. In an email, the RSPO wrote that it would be “challenging” to estimate when the complaint would be resolved and noted the “voluminous” quantity of evidence that the investigator would need to review. In the meantime, major traders appear set to retain First Resources as a supplier.

“It's very concerning that traders have not taken the report seriously and initiated investigations or suspensions,” said RAN’s Gemma Tillack. “This is part of a wider trend where the biggest agribusiness traders are refusing to take the corporate group issue seriously.” Tillack noted that some traders - which are also major palm oil producers - have also been accused of operating shadow companies. "Brands can’t rely on their suppliers - they will not be acting in good faith to get a clear resolution on the case," she added.

Almost all the consumer goods firms we contacted stated that they were monitoring the progress of the RSPO complaint. Some insisted that the RSPO was the appropriate body to investigate the allegations against First Resources. The margarine manufacturer Upfield said it viewed the RSPO as “the arbiter of such allegations,” while Barry Callebaut called it the “main platform for investigation” for the body’s members.

Campaigning groups are now pushing for regulations that require companies to investigate wrongdoing in their supply chains themselves, wherever it occurs. The length and complexity of global supply chains can make this challenging, consumer goods firms argue. But years of voluntary commitments to human rights and environmental standards have not achieved enough, according to Mathieu Vervynckt of the nonprofit SwedWatch, which conducts research on sustainable supply chains. “We’ve tried the carrots. There’s a need for a stick now,” he said.

These efforts have had some success. Last year, the German government passed an act requiring companies with a significant presence in the country to identify potential risks to human rights throughout their supply chain and take “appropriate preventive measures” to address them, with fines for non-compliance of up to 2% of annual global turnover.

Significantly, the German act requires companies to respond when they are presented with evidence of potential violations committed by their indirect suppliers - not just those with which they have a direct commercial relationship. In January, a complaint submitted under the act demanded that the German company Edeka investigate allegations that its indirect palm oil suppliers in Guatemala had committed human rights violations. “The complaint shows that under the German supply chain law, companies can't just say, ‘We don't have to do our own risk analysis - the RSPO does it for us,’” said Annabell Brüggemann of ECCHR, one of the nonprofits that filed the complaint. Edeka told reporters it is examining the allegations in line with the new law.

Similar measures could yet take root across Europe. In December, after several years of discussion, negotiators reached a political agreement on an EU directive requiring large companies operating in the bloc to monitor their value chains even more closely. The directive, known as the CSDDD, includes measures obliging companies to check whether their indirect suppliers are taking steps to minimise and prevent deforestation.

However, on 15 March, following sustained opposition from groups in several EU member states, the number of companies subject to the CSDDD was cut by almost two thirds. Some companies may have had a vested interest in limiting the law’s coverage: according to research by the nonprofit Earthsight, one German company whose CEO lobbied extensively against it has bought clothing from a firm accused of using child labour.

If the directive is approved by the European Parliament in April, EU member states will have two years to transpose it into national law. Elsewhere, legislators in countries including the UK, Japanand South Korea are also proposing similar laws. “It's important that companies realise mandatory due diligence legislation is coming up everywhere in the world,” said Amandine Van Den Berghe, of the environmental law nonprofit ClientEarth.

In the meantime, activists are arguing that consumer goods companies with links to First Resources need to take decisive action. “Any responsible company that is serious about supplying deforestation-free palm oil should immediately suspend First Resources, regardless of how long the RSPO dithers in addressing the complaint” said Amanda Hurowitz, senior director for Asia at the nonprofit Mighty Earth, which has been monitoring deforestation since 2016. "Failure to act is inexcusable.”

While First Resources repudiated the findings from The Gecko Project’s investigation in a statement last November, it wrote in response to the latest developments that it “recognises the seriousness of the allegations” and has “brought on independent support to investigate these issues and identify an action plan”.

The company said that it was cooperating with the RSPO complaint, and asked for “all parties to respect the ongoing process and await the result before drawing conclusions or making any claims.”

Read more reporting from The Gecko Project on corporate accountability here.

Join The Gecko Project's mailing list to get updates whenever we publish a new investigation.

Header image: Discarded palm fruit. By Jamie Wolfeld/Forest Peoples Programme.