- Across Indonesia, hundreds of communities are in conflict with companies seeking control of their resources. In some cases, the resistance has been led by women.

- Journalist Febriana Firdaus travelled across the country to meet grassroots female activists and delve into the stories behind their struggles.

- This article is part two of a series about her journey, which has also been made into a film, Our Mothers’ Land. Read part one here.

- Photos by Leo Plunkett, illustrations by Nadiyah Rizki.

It’s raining, windy, and misty as I head toward the village of Fatumnasi. It’s almost impossible to traverse this clay-and-dirt road in a car, so I’ve hired a motorcycle taxi to take me into the highlands of Timor, an island in eastern Indonesia.

I am more than 2,600 kilometers (1,600 miles) from Jakarta, the nation’s capital. I’m much closer, in fact, to the northern coast of Australia, a reminder of how vast this sprawling archipelago is.

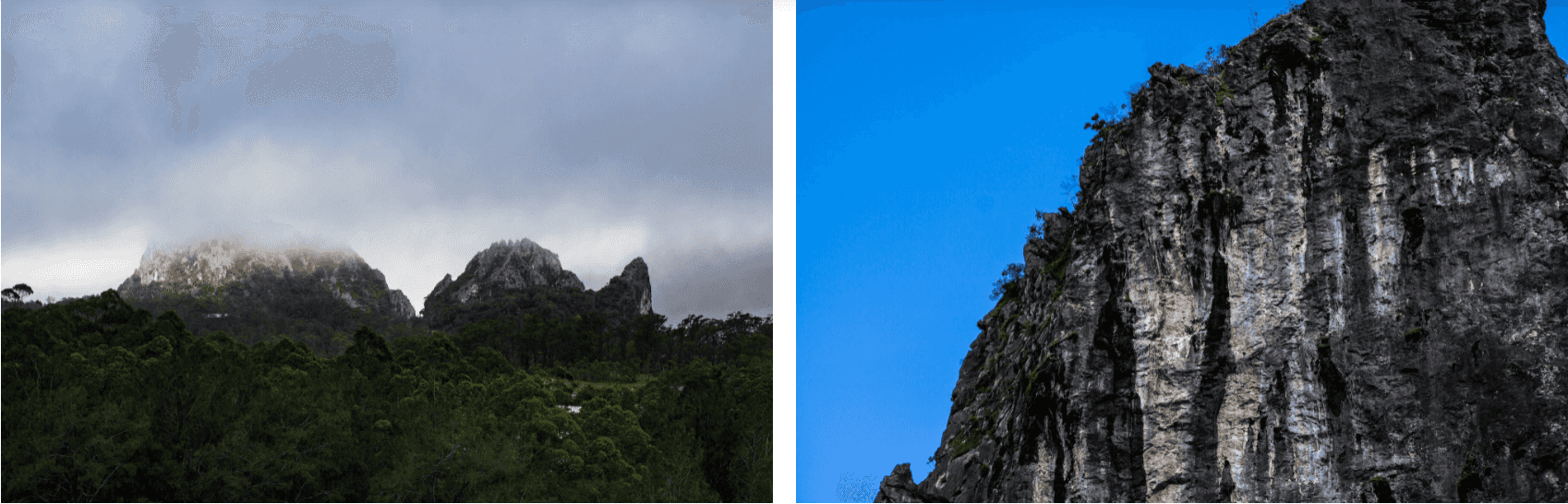

From Jakarta, it’s a two-hour flight, then a four-hour drive through hills covered with green grass that merge into rocky mountains. It’s the rainy season and our surroundings are concealed by mist; we can see no more than 10 meters ahead.

This is not my first visit to this part of Timor, once a kingdom known as Mollo. In 2016, I came here with Christian Dicky Senda, a poet from Mollo who wrote a collection of short stories set in his homeland. He introduced me to Matheos Anin, an elder who runs a homestay.

Matheos welcomed me to his bulbous house, known as an ume kbubu. He lived there with his wife, along with their chickens, pigeons, dogs, and a weasel. People in Mollo, most of whom belong to the Dawan tribe, live from farming and raising cows and horses. They use their houses not only to sleep, but also to shelter their animals and store crops. I was immediately captivated by the people, their homes and the landscape.

This time, when I arrive in Fatumnasi after hours of careful driving, I am not exactly sure who I am going to meet.

The village is in the far north of Mollo, the gateway to Mount Mutis, the island’s highest point. For more than a decade, beginning in the late 1990s, the women here led a string of mass protests to stop mining companies from extracting marble from their sacred rocks.

I’m here on the second leg of my journey across Indonesia, meeting women who have taken a stand against companies intent on exploiting their natural resources. A few days before, I was in the cornfields of Kendeng on the island of Java, to meet women who had encased their feet in cement before the Indonesian presidential palace. They had done so to protest a plan to mine the limestone karst that provides hundreds of thousands of people there with clean water.

Like the Kartinis of Kendeng, as those women were known, the female protesters in Mollo attracted a degree of fame. One of them, Aleta Baun, who was widely credited with leading the movement, received the 2013 Goldman Environmental Prize, a prestigious international award that recognises grassroots activists.

During the protests, hundreds of women reportedly occupied mining sites for months on end. In a decision that would give the protest its defining identity, they brought their looms to the site, and whiled away the days and weeks by weaving their traditional tenun cloth: a display of indigenous culture at odds with the defilement of their sacred mountains.

The thought of them weaving in protest was at once evocative and intriguing. I wanted to understand the story behind the movement by meeting the women involved. I knew little of what had happened to them in the intervening years after the protests had subsided. Perhaps, I thought, these misty mountains might hold lessons for other women across Indonesia who are fighting to protect their lands.

I would begin to grasp the toll exacted on these women by their participation in protests; how they felt they had no option but to take action, but did not escape unharmed.

But where to begin? Most Fatumnasi residents today are too young to have been involved. Some of those who were have already passed away. But eventually, I find one of the women at a small farm. Her name is Lodia Oematan.

Unlike Aleta Baun, who became known as the figurehead of the protests, Lodia remained out of the spotlight. In fact, she says, it’s the first time she’s spoken to the media about the protests. Wearing a T-shirt and a tenun wrap, with her dark hair tied back, she looks younger than her 60-plus years. But the wrinkles on her face tell me she is old enough to be a grandma.

During our conversation, she sometimes speaks very slowly, before her tone sharply rises as she expresses her disappointment, anger, and sadness at the events that unfolded. She takes me back to the moment she was drawn into the protests.

In August 2006, she was returning home by motorcycle taxi from a wedding in Timor Leste, the tiny nation that shares this island with Indonesia, when she passed a sacred rock, Faut Lik. There, she says, she saw policemen, members of the army special forces, an excavator, and other men she described as hired “thugs.” The men dismissed her questions, saying they had simply come to establish a pond for fish farming.

In fact, workers from a mining company had turned up with the excavator the day before. They had torn down the fence of a local woman named Ety Anone, to carve a road toward Faut Lik.

Ety had quickly discerned that these were miners intent on extracting marble from the limestone rock. She had climbed the excavator and engaged in a shouting match with the workers for two hours before they stood down, as villagers gathered around the clamour. Now the miners had returned, with protection.

Lodia called their bluff and yelled at them to stop. The locals knew how to make fish ponds, she said, and had never done so on top of a mountain.

“Forgive me,” Lodia tells me modestly, before explaining that she had bared her breasts at the police. She recounted shouting at them, “I have these big breasts, this big belly, because everything on this land — soil, rocks, water — made it possible for me to have these.

“This land belongs to the people,” she said. “If you snatch the land, it’s like you take away our plates, spoons, food. Then how are we going to eat? Sure, you will eat as much as you can, but we people will suffer until our death.”

By this point, people in Mollo had been protesting against mining firms and the government that provided them with permits since the 1990s. A 2014 paper by Torry Kuswardono, an academic who runs a local NGO, chronicled the resistance to these companies across a large swath of West Timor.

Springs emanating from the mountains supply people with clean water across Mollo. But these natural features also have a deep cultural significance. Some clans draw their names and identity from specific bodies of water or trees, and many of them from the stone outcrops like Faut Lik that jut strikingly out of the ground.

“Water is blood, forest is hair, soil is flesh, stone is bone.”

These faut kanaf, or “name stones,” are sacred sites associated with epic origin stories, places where advice or strength can be sought from ancestors. In the local language, they say Oel nam nes on na, nasi nam nes on nak nafu, naijan nam nes on sisi, fatu nam nes on nuif: “Water is blood, forest is hair, soil is flesh, stone is bone.” These rocks are considered the backbone of life.

Torry noted that locals were not inherently opposed to mining. But any activity that threatened to damage a name stone would generate fierce resistance. “If they allow their sacred places to become damaged,” he wrote, “it can bring a curse from the ancestors unto themselves, their children and their grandchildren.”

In 1998, after the governor of East Nusa Tenggara province, which includes the Indonesian part of Timor, issued a spate of mining permits, a company began mining on one mountain, Fatu Nausus. After seven months of sending letters and negotiations between elders and the government, hundreds of people from 12 villages gathered at the mountain, forcing the company to halt its operations.

But instead of recognising their opposition, the new governor, Piet Tallo, reassigned the permit to a new mining company. In Torry’s account, this gave rise to Aleta Baun’s “epic resistance.” She sought the support of her extended family and NGOs, eventually gathering 3,000 people — men and women, young and old — to occupy Fatu Nausus. Some would stay for three months. By 2001, they had deterred any companies from mining the rock.

Five years later, as Lodia described, miners returned. Faut Lik and Fatu Ob were sacred rocks a short distance from Fatu Nausus, and now they were in the sights of a new firm.

“If they allow their sacred places to become damaged it can bring a curse from the ancestors unto themselves.”

During the week following the excavator’s arrival, according to a chronology of events published by Aleta Baun in 2006, the police pressed the villagers to give up their land. More than 100 villagers descended on the district parliament building, entreating its members to protect Faut Lik. Still the excavator kept carving a road toward the mountain.

By the end of the month, Ety Anone, Lodia and another woman had taken to physically blocking its path. But whenever they returned to their homes, to tend to their families and farms, its advance would begin again.

By October, the miners had reached the rock. By then, some 100 women had assembled at the site, coming face-to-face with the workers and security forces. Every day they would arrive at 4 a.m., Lodia recalled, racing to get there before the miners and staying until night.

“We had to hurry and get there first before those thugs did,” she tells me. “They would never back off, but neither would we.”

Before long, the women had devised a system to guard the rock in shifts around the clock. By night, the men would sleep in tents in the cracks of the rock; by day, the women took over the site, singing and weaving.

“Let them bring their best weapons, but we will stand our ground to take back what is ours.”

Lodia said the weaving was a symbolic act, that they were weaving the tenun to metaphorically “wrap it around the marble.”

“As if the marble field is a ball, we wanted to show that it belonged to us by working hard wrapping it,” she says. “We wanted to show them that the land belongs to the people, regardless if we’re still alive or dead.”

The miners’ machines worked around them, Lodia recalls, but they “didn’t scare us a bit.” “I shouted, ‘Resist! Resist!’ The drilling machine was right next to me, but I carried on weaving.”

For all their bravery, the women faced attacks from the “thugs” who, the protesters believed, had been hired by the company. She described being thrown to the ground and “beaten hard” during the protests.

The women were tougher than they may have appeared. Despite the violence, they would not be deterred. “Let them bring their best weapons, but we will stand our ground to take back what is ours,” Lodia recalls thinking. “We will never stop until we can take it back.”

The violence was not unprecedented. A protest earlier that year against another mining company operating nearby had escalated quickly into violence, according to a statement issued by NGOs at the time. Kelik Ismunandar, a local activist working with the communities, reported that the police had failed to protect the protesters, and had subsequently arrested dozens of them.

After a month of occupying Faut Lik, dozens of villagers from Fatumnasi and other villages staged a two-week sit-in at the office of the district head, Daniel Banunaek. He refused to meet them, Kelik said, and their protest was broken up when a mob turned up and attacked them, chasing them out of the office. (Daniel was later jailed for illegal logging.)

Three months later, in March 2007, the villagers went to court to try to stop the mining. The hearing, in Soe, the district capital, never got underway, as the clerk failed to turn up. But as Aleta Baun and other villagers left the courtroom, they were set upon by a mob and assaulted.

Yet their spirit remained unbroken. By mid-2007, the villagers had succeeded in repelling the miners. By this point, since the late 1990s, the villagers around Mollo had succeeded in stopping three companies from desecrating their sacred stones. Each time, it seemed, the resistance was simply too strong for the companies.

Their efforts took a huge toll. Lodia tells me her sister suffered permanent disabilities from injuries she sustained during the occupation. Lodia herself suffered from stomach infections after she was stamped on. “I was beaten up pretty good,” she says. “I’ve barely recovered now.”

For eight years, she tells me, her injuries prevented her from working in the fields. She struggled to feed and clothe her children and pay their school fees. “It was miserable,” she says. “My tears ran dry.”

Looking back today, the fierce demeanour of her younger self fading, she questions whether the sacrifice she made was worth it. “I’m filled with sorrow and regrets,” she tells me. “If only I hadn’t joined the movement, it would be easier for me to provide for my kids.”

“These mamas had dreams. But they had to forget them when they joined the struggle.”

I have no idea how many other women spread throughout these hills harbour the same regrets. Caroline Monteiro, a feminist and activist with a decade of experience in eastern Indonesia, told me that many suffered from physical and psychological wounds. “The problem is that there was no counselling after the protest, and actually they really need it,” she said.

I leave mist-clad Fatumnasi, and Lodia, feeling confused. The women had seen no option but to take a stand. But their battle carried such a high price. It changed their lives forever. “These mamas, including Mama Aleta, had dreams,” Caroline said. “But they had to forget them when they joined the struggle.”

Was the sacrifice worth it? To find the answer, I arrange to meet Aleta Baun at Fatu Nausus.

For the first time, I see the sacred rock. It’s slippery as I climb, formed of giant marble stones. But it is half cut now; some of the sides are broken. I can see a broad gash stretching across it.

From the top, I can see across Timor Island. Sitting here with Aleta, I feel a profound sadness.

The mountain didn’t always exist, Aleta tells me. According to legend, three women on a journey once took shelter here to breastfeed their children. The women turned into the mountain, and it became known as Nausus.

“The word Nausus means ‘to embrace and nurse,’” Aleta says. “So this mountain is called ‘the breastfeeding mountain.’”

The story is rich in symbolism. These mountains protect the headwaters of rivers across West Timor. “There’s no mountain here without a spring,” Aleta says. “They have pores underneath them, which act as water reservoirs.”

The rivers, in turn, feed the people and irrigate their lands. It is these sacred stones that nurture them, like a mother. I think back to the Kendeng farmers, from the first leg of my journey. They considered the limestone karst that provided them with water as their mother, too.

When mining came to Fatu Nausus, it was as if their mother was under assault. People come together not only to protect their water, but to defend Mother Earth. Both Fatu Nausus and the Kendeng karst were given feminine form, and in both places, women took the lead as their guardians.

Although women came to lead the protests, Aleta still had to struggle for her position at the forefront of the movement. Her father is an amaf, a ritual leader responsible for enforcing customary laws stewarding the community’s land. That made her an elite within Mollo’s social structure. But she was still a woman.

“We organised the people by reminding them about our forgotten history. One that had been eroded by time.”

For years, Aleta sought to prove to the all-male elders that she could organise protests to stop the mining, just then emerging, that she feared would cause terrible harm to their land.

“Because I’m not a man, I had no mandate to tell those leaders what to do,” she says. “I’m a woman, and the women are usually given no mandate whatsoever.”

But she suspected that it might be different, by the late 1990s. She traveled from village to village by foot, some six hours away from each other, to convince people to rally to the cause. “We organised the people by reminding them about our forgotten history,” she tells me. “One that had been eroded by time.”

As time went on, Aleta won widespread recognition for her actions, breaking through the patriarchal social structures to lead thousands of people for more than a decade. In 2014, she was elected to the provincial parliament for a five-year term.

Many of the conditions that gave rise to the movement remain unchanged. Aleta suspects companies are still seeking mining permits. But, she tells me, the years of struggle have increased the ability of Mollo’s people to control their fate.

“What’s interesting to me is that the indigenous peoples’ knowledge has been strengthened, of philosophies that are deeply related to nature,” she says. “This enables people to make informed decisions.”

Mollo tradition demands that people only sell what they produce; they can’t sell the rivers, the land, or the mountains. The women I met live by that philosophy. Lodia earns money by weaving traditional cloths that she sells to visiting foreigners. Aleta maintains a tourism village near Fatu Nausus. But they cannot escape the legacy of those who pursued another creed, who inflicted harm on their mountains and bodies.

I leave Mollo at 9 in the morning, uncertain what the future will hold for these women. As my car pulls out of the village, I get a last look at Fatu Nausus shrouded in clouds, as if they want to protect her. As I gaze at the majestic site, Aleta’s words ring in my ears.

“Nature is a vast library, and there’s a unique way for us to learn from it,” she had told me. “And I have learned more from nature than from the humans who deceived me.”

To see other articles, films and photos from The Gecko Project as they come out, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube. Sign up to our mailing list here. The Gecko Project stories are available in Bahasa Indonesia at our Indonesian site here.