Baca versi artikel ini dalam Bahasa Indonesia yang diterbitkan oleh Tempo.

- One of the world’s largest palm oil producers appears to have secretly controlled a network of companies that have been clearing rainforests in Indonesia for more than a decade, an investigation by The Gecko Project has found.

By committing publicly to conserve forests, Singapore-listed corporation First Resources was able to brand itself “sustainable” and sell palm oil to major consumer goods firms in the US and Europe.

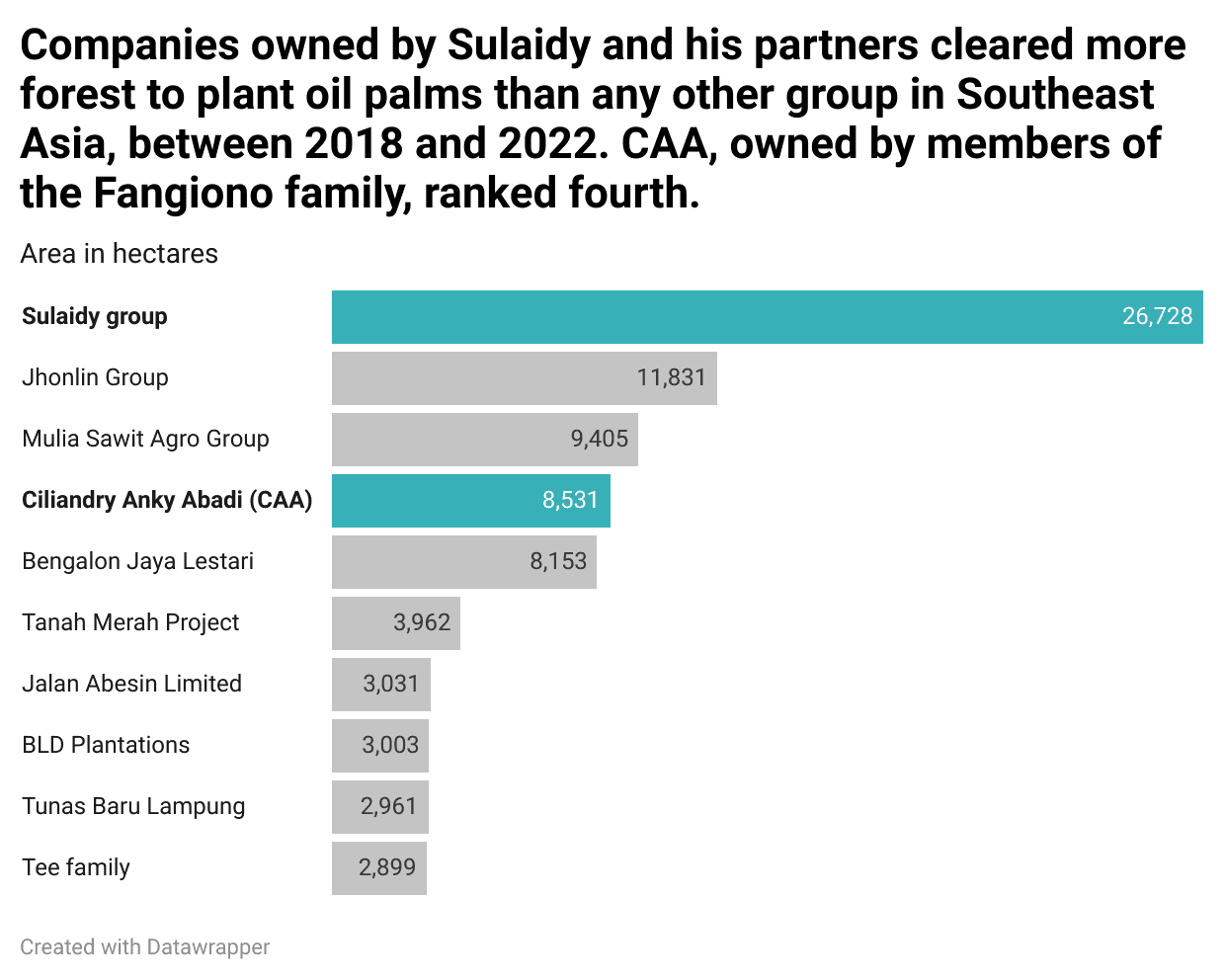

- But through an apparent network of “shadow companies,” First Resources has destroyed more rainforest for palm oil over the last five years than any other corporation in Southeast Asia.

- First Resources has consistently denied operating shadow companies. Despite this, insider testimony and corporate documents provide evidence that the corporation - and members of the billionaire Fangiono family, which owns First Resources - oversaw the shadow companies’ activities as they bulldozed through swathes of Indonesian Borneo.

- The investigation adds to mounting evidence that major palm oil and timber firms are using shadow companies to evade restrictions imposed by voluntary sustainability schemes.

This investigation is part of Deforestation Inc, a collaboration coordinated by The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists involving reporters from 28 countries. Find out more here.

For the past half decade the district of Siluq Ngurai, in Borneo, has been at the centre of a mystery.

Over that time, a handful of companies have methodically cut down the rainforest that once stretched across this part of Indonesia, transforming a landscape teeming with life into monoculture oil palm plantations.

The question was, who was behind the companies?

Corporate filings revealed a common thread — an Indonesian man with one name: Sulaidy. He had held most of the shares in the firms until 2017. That year a new partner came on board. But their identity was hidden in an offshore jurisdiction.

There was a clear motive to find out who was controlling the companies. By the time they began operating in earnest, most major palm oil producers and traders had committed to keep forests standing, after years of pressure from consumers.

If environmental activists could prove a link between Sulaidy and any of these apparently sustainable companies, maybe they could pressure him to turn off the bulldozers. But for the activists on his trail Sulaidy remained an enigma, with scarcely any online footprint. As his companies destroyed thousands of hectares of rainforest, his identity — and that of his partners — remained a closely guarded secret.

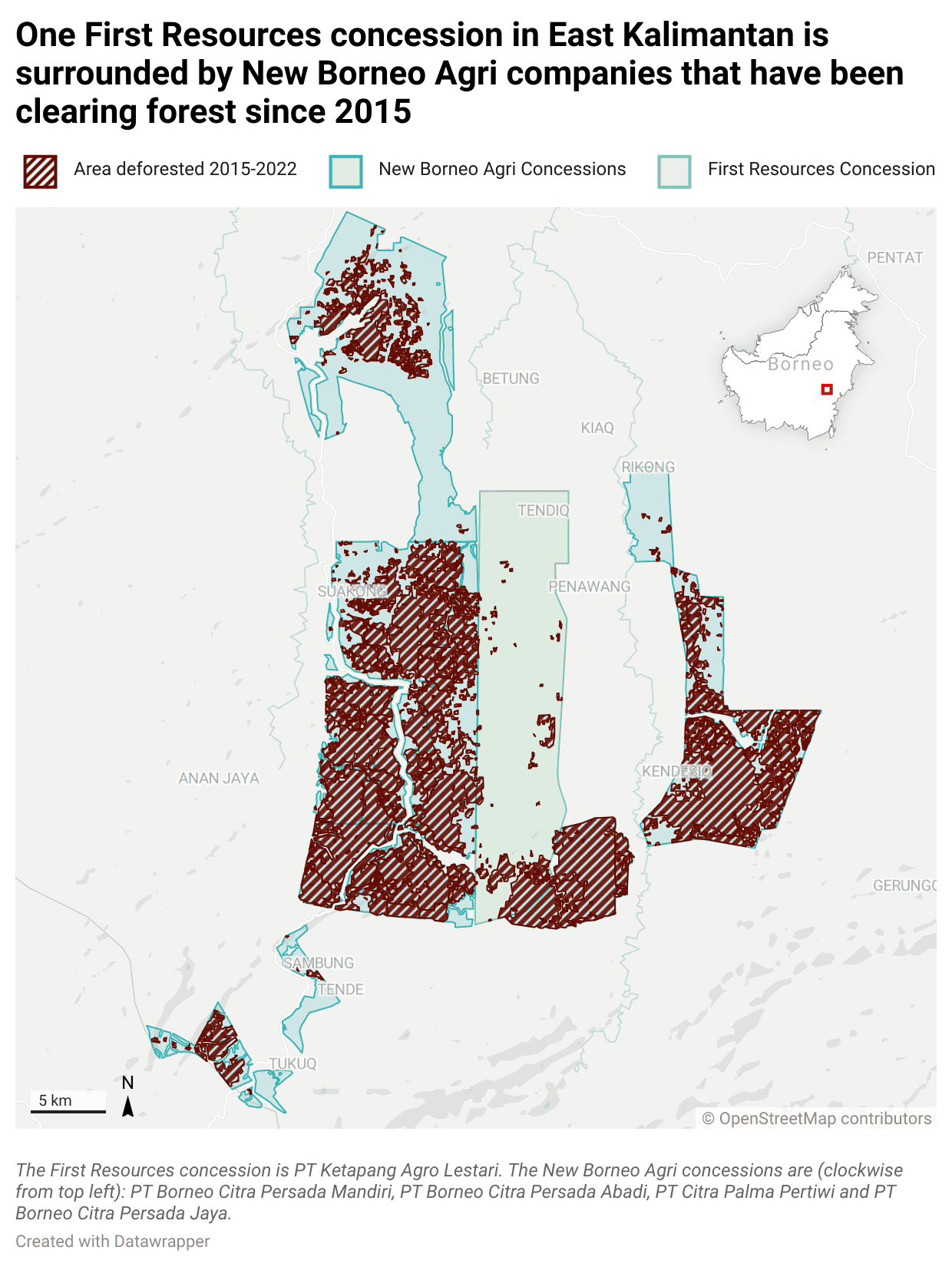

An investigation by The Gecko Project reveals evidence suggesting that these companies were the hidden arm of one of the world’s largest palm oil producers. First Resources, a firm majority-owned by the Fangiono family, made its own public pledge to stop clearing forests in 2015, allowing it to continue selling palm oil to consumer goods firms such as PepsiCo and Procter & Gamble.

While the elusive Sulaidy appeared on corporate records, the investigation found that First Resources was the controlling hand behind this sprawling network of so-called “shadow companies.” As First Resources sold to buyers in Europe and the US that had committed to deforestation-free supply chains, the Fangionos’ secretive companies ploughed through rainforests across Borneo.

The footprint of these companies is so large that for the past five years, as it maintained the facade of a sustainable company, First Resources cleared more forest for palm oil than any other company in Southeast Asia.

First Resources and the Fangionos have long been trailed by allegations that they are operating shadow companies. These were first aired in 2018, when nonprofit organisations monitoring forest clearance identified connections between the company and three other ostensibly independent groups — including the Sulaidy companies. A string of clues put together by activists led to the door of First Resources. But First Resources repeatedly denied or evaded allegations that it owned or controlled the groups.

The Gecko Project interviewed 14 people who worked for First Resources and the alleged shadow companies between 2011 and 2022. These interviews revealed that, for many employees, the divisions between the companies were functionally non-existent.

Employees worked seamlessly across the groups — some moved from First Resources to work at the Sulaidy companies, others worked in a single office to analyse data from both the “sustainable” arm and companies that were clearing rainforest. Their work was overseen by an executive who has worked for the Fangiono family since the early 2000s. The employees ultimately answered to Ciliandra and Cik Sigih Fangiono — the billionaire brothers who are the public face of First Resources.

While First Resources repudiated or ignored allegations it was linked to the shadow companies, internally — from its training centre, to plantations, to offices — managers made little effort to disguise the fact they were one corporation. First Resources employees were even named as legal representatives of the Sulaidy companies, documents obtained by The Gecko Project show.

“We thought it was normal, because I knew from the beginning: it’s all First Resources,” said an employee who spent several years working for subsidiaries of First Resources and its shadow groups. “The management is the same, a lot of things are the same. There was nothing strange about it.”

Responding to media approaches, First Resources restated its denial that it owns or controls the shadow companies. It wrote that the Sulaidy group “is not a subsidiary, an associated company, nor a related party of First Resources.” Ciliandra Fangiono and Cik Sigih Fangiono did not respond to a request to comment on a detailed list of The Gecko Project’s findings.

First Resources may not be the only company using complex shareholding arrangements to hide its involvement in deforestation. Voluntary corporate commitments to “zero deforestation" have now expanded to cover most of the international trade in agricultural commodities most responsible for the clearance of tropical rainforests. In Indonesia, forest loss driven by oil palm has plummeted, a development that has been credited to these private sector measures as well as government policies.

There is mounting evidence, however, that major firms involved in the production and trade of palm oil and timber products have sought to circumvent the restrictions imposed by their own policies by establishing shadow companies.

In some cases, these shadow companies are owned on paper by different members of the same family, creating artificial boundaries between what is functionally one conglomerate. In others, the ownership is hidden through secrecy jurisdictions, deploying methods more commonly associated with corruption and tax evasion. Either way, it allows conglomerates to maintain access to “sustainable” markets through one arm, while another destroys rainforests and stokes conflicts with communities.

“In the world of plantations, it seems it's common,” said a former Fangiono company employee. “It's an open secret.”

Beginnings

The origins of First Resources are rooted in the downfall of its founder, Martias.

Martias, who goes by one name, was born in 1948 in Bengkalis, a small port town on an archipelago that hugs the east coast of the Indonesian island of Sumatra. For entrepreneurs of Martias’ generation, timber was the biggest game in town. Sumatra was richly forested, and the rapidly-growing Asian tiger economies were hungry for plywood.

Martias established Surya Dumai Industri, a company that operated plywood mills in Bengkalis, when he was still in his early 30s. By the 1990s it had expanded into timber plantations, become one of Indonesia’s ten largest palm oil producers, and was listed on the Indonesian stock exchange.

His troubles started in the early 2000s. Indonesian officials discovered he had masterminded a scheme to gain illegal access to a vast area of rainforest in Borneo, instructing subordinates to secure licences for oil palm plantations, sidestepping complex and costly legal requirements, then logging the land. Officials discovered that Martias’ companies had planted barely any oil palms, raising doubts over whether they had ever intended to do so.

In his 2007 trial, Martias’ defence cast doubt on whether he actually owned the companies involved in the scheme. The permits for the plantations had been obtained using a dozen different companies. Officials had been led to believe they were part of the Surya Dumai Group, but discovered during the investigation that an entity of that name didn’t exist. It was just used for “marketing purposes,” according to Martias. The companies had a string of different shareholders, and Martias claimed that he was only acting as a “corporate supervisor” on behalf of other people.

A law professor testified at the trial that without a legal entity acting as a holding company, “it’s just a fiction” or “a shadow.” A forestry official sent to investigate the scheme admitted that proving, de jure, that the companies were all part of a single group was “very difficult.” However, he concluded that they had to be; the companies shared the same office and were represented by the same individuals. There were overlaps between their shareholders and board members. Several witnesses testified that Martias oversaw and owned the group.

The court ruled that Martias was the “controller” of the companies, and responsible for their sins. It was a major scandal, which brought down senior forestry officials and the governor of East Kalimantan. Martias was convicted of corruption, sentenced to one-and-a-half years in prison and ordered to pay a $38 million fine. Surya Dumai Industri collapsed, and was delisted from the Indonesian Stock Exchange.

Martias may have lost, but his defence foreshadowed the way the family business would go on to be run. And that family business was far from finished. At the same time that Martias’ logging scandal was playing out in court, his eldest son, Ciliandra Fangiono, was preparing to take another company — First Resources — public.

If the Surya Dumai Group was a crumbling, corrupt empire overseen by a disgraced logging baron, First Resources appeared an altogether different entity. Ciliandra, named CEO in 2007, was just 30 years old. A graduate of Cambridge University, he was seeking the respectability of a public listing on the Singapore stock exchange, which would mark a major milestone on his way to becoming Indonesia’s youngest billionaire.

Documents published by First Resources to promote its IPO revealed that Martias was one of its founders (no other founders were named). The company’s operations and assets were all located in Martias’ home province. But, the company claimed, he no longer had anything to do with the business, which was owned by six of his children.

Nevertheless, the Surya Dumai scandal threatened to pull First Resources down along with its founder. In 2008, Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission, or KPK, went looking for properties that it could seize and auction off to recoup Martias’ enormous unpaid fines, and identified three plantation companies owned by First Resources as possible targets.

The news sent First Resources’ share price tumbling; its credit rating was revised to negative. Ciliandra rushed to reassure the markets, telling investors the day after the announcement that the KPK had made a mistake. “Our assets are clean,” he said. They were nothing to do with the court case, save that the KPK had identified them “as a means of recovering the financial penalty”.

Within a week, Martias had paid his $38 million fine in full, and the KPK called off the chase.

First Resources would soon find another way to distance itself from Surya Dumai and shake off the taint of Martias’ downfall.

The paper trail

By the mid-2000s, the palm oil industry was synonymous with the destruction of tropical rainforests. Vast areas of Southeast Asia’s forests were being cleared to meet the demands of the global food and cosmetics industries, destroying the habitats of critically-endangered species, and endangering the heritage and livelihoods of indigenous peoples.

In response to rising criticism, palm oil producers, consumer goods firms and conservation groups got together to create the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, or RSPO, whose members commit to respecting indigenous rights and biodiversity, and to commissioning independent assessments on land ownership and habitats around each of their projects. First Resources joined the RSPO in 2008, soon after it went public. It was a sign to investors, buyers and the world at large that this was a “sustainable” company.

For activists pushing companies to stop clearing rainforests, however, the RSPO did not go far enough. Companies could still clear rainforest, just as long as it was not “primary” — undisturbed by humans — and did not contain orangutans or other endangered species. Images of the bright-red apes seeking refuge in charred landscapes, in concessions belonging to RSPO members, raised doubts over whether the system was up to scratch. As campaigns from groups, including Greenpeace, began to bite, the world’s largest traders and then producers of palm oil started going further — committing to leave all forests standing. First Resources made its own public zero deforestation pledge in 2015.

Activists' work switched, from pushing for the industry to adopt these policies, to monitoring whether they were being implemented and chasing the laggards. Advances in satellite imagery analysis meant that from a laptop in Jakarta, London or San Francisco, they could now see what was happening in rainforests thousands of miles away in near real-time. If the tell-tale signs of industrial-scale deforestation popped up in Borneo or Papua, they could overlay government concession maps to identify the company in control of the land.

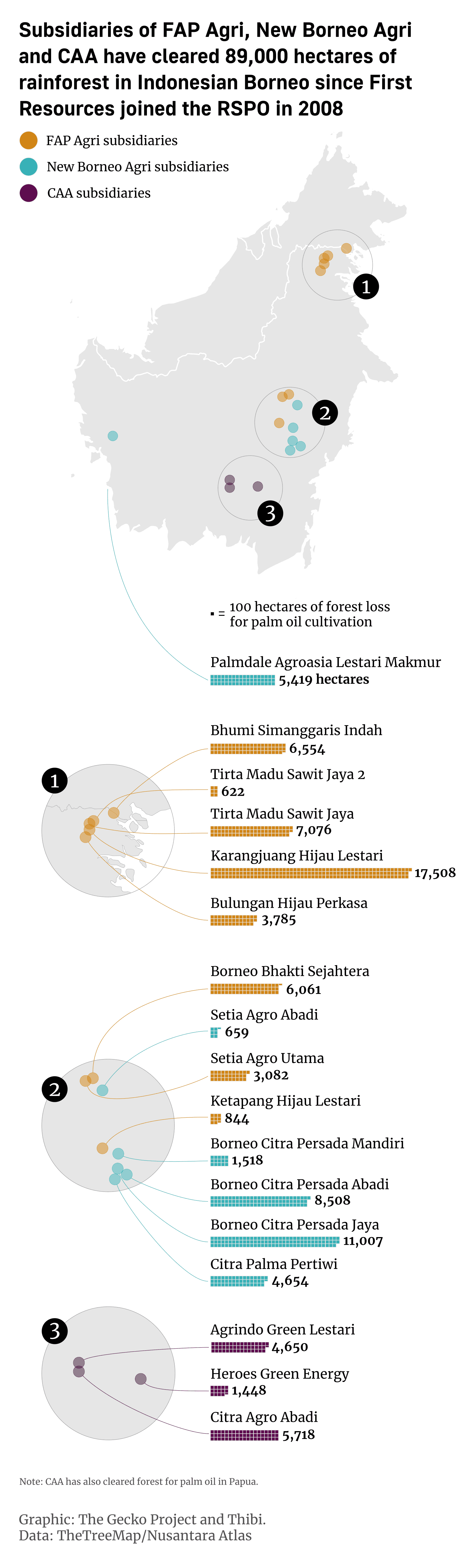

By the late 2010s, attention from activists and researchers began to coalesce around three such laggards. One, Ciliandry Anky Abadi, or CAA, was cutting into orangutan habitat in Central Kalimantan, a province on the island of Borneo. Another, Fangiono Agro Plantation (later renamed FAP Agri) had also cleared thousands of hectares of forest.

The nonprofit Forest Peoples Programme, known as FPP, collected extensive evidence of conflicts between FAP Agri and indigenous Dayak Agabag and Dayak Tenggalan communities in remote parts of Borneo. Villagers' land was being taken without their consent, and those who opposed were subject to arrest or threats from the armed police and the military, according to FPP.

“A lot of communities were very fearful about speaking out,” said Angus MacInnes, a researcher with FPP. “It's deeply troubling for the Dayak Agabag, who are living in a climate of fear.”

And then there was the Sulaidy group. By the end of 2018, this collection of companies had shot to the top of the deforestation chart — clearing more forest for palm oil than any other in Southeast Asia that year.

Activists were convinced the three groups were linked — to one another, and to First Resources — to the extent that they should be treated as one company. Corporate records showed that CAA was owned by a woman Greenpeace identified as Martias’ second wife and two of their children, half-siblings of First Resources CEO Ciliandra. For years, the majority ownership of FAP Agri was hidden in a secrecy jurisdiction, before the company underwent an initial public offering of its own, in 2020, and the major shareholder was revealed to be Wirastuty Fangiono — Ciliandra’s sister and a major shareholder in First Resources.

Researchers at Greenpeace unearthed multiple other overlaps between the firms. For eight years, CAA had shared an office address with First Resources’ main Indonesian subsidiary. Two men who had served as commissioners for CAA subsidiaries had played similar roles in Surya Dumai Industri and First Resources. Both of them had also been called to testify at Martias’ trial: Citra Gunawan as the director and Lau Cong Kiong as an accountant for several of the companies involved in the scheme.

FAP Agri had also used the same address as First Resources. Citra Gunawan and Lau Cong Kiong appeared as directors and commissioners of the company. Greenpeace surmised that the two men were “Martias’s long-term business colleagues” who were “supporting the young Fangionos in establishing and managing their business empire.”

“For me, the links were very obvious from the beginning,” said MacInnes.

The Sulaidy group lacked the same ownership links to the Fangionos — it was majority-owned by Sulaidy himself, until most of the shares disappeared into a secrecy jurisdiction in 2017. Activists could find little public information about Sulaidy beyond his name and a partial address. But corporate records pointed to a string of long-running connections between him and the Fangionos. He had held shares in FAP Agri and part-owned a company with First Resources. Citra Gunawan and Lau Cong Kiong had previously been named as executives in companies owned by Sulaidy. Lau Cong Kiong had been the director of Sulaidy’s holding company, through which he owned the plantation firms, when it was incorporated. That company was registered to the same floor of a Jakarta tower block as First Resources’ corporate offices.

Despite the weight of evidence, First Resources issued statements repudiating the links to CAA and FAP Agri alleged by activists. FAP Agri was a supplier, but “not a subsidiary or an associated company of First Resources”; both groups had “distinct and independent managements”. (FAP Agri also insisted there was “no relationship between First Resources and FAP Agri in terms of ownership or management”). CAA was “not a subsidiary, an associated company, nor a related party of First Resources” and there were no overlaps in ownership or management.

On the Sulaidy group, it was more circumspect, and did not comment on the allegations levelled by activists.

What mattered was what the palm oil traders, buyers and RSPO believed. If they assessed the allegations to be true — that this should be treated as one group — their own rules would compel them to demand a cessation of deforestation and a plan to resolve conflicts with communities. If they failed to do so, in theory, First Resources could be blacklisted — potentially cut off from the three quarters of the trade now covered by zero deforestation policies.

In 2018, some major consumer goods firms told Greenpeace they would stop buying from any of the companies linked to the Fangionos, including First Resources. But many more continued buying. The RSPO dragged its heels, a formal allegation that First Resources had “ownership, control and influence” over both FAP Agri and CAA winding its way slowly through the body’s complaints system without resolution.

In Borneo, the conflicts with Dayak communities simmered and forests continued to fall. By 2023, disclosures by consumer goods firms and traders — Colgate-Palmolive, Procter & Gamble, PepsiCo, Cargill and more — revealed that palm oil from First Resources continued to flood into the “sustainable” market.

Meanwhile, according to sources inside the company, the family’s control of this empire was clear.

Inside the empire

Many of the people who came to work for the Fangiono family first had to pass through First Resources’ training centre, which occupies a campus surrounded by palm trees outside the Sumatran city of Pekanbaru.

Asep applied after learning about a vacancy through the job board at his university career centre in 2018. Within two weeks, he was on his way to Pekanbaru. A fresh graduate, eager to get his career underway, the speed was appealing. “We didn't know what kind of company it was,” he said. “What's important is the money.”

The programme was demanding: up at 5am to exercise, breakfast, then classes from 8am until 5pm. “The main thing was learning how to manage a plantation:the organisational structure, the leadership.” After learning theory, they’d spend time at First Resources’ plantations in the same province, putting it into practice. The trainees were asked to sign forms consenting to be sent wherever the company needed them. Those fortunate enough to pass — only half, by one account — were “scattered” across Sumatra and Borneo.

After he graduated from the training centre, Lambok found himself in Long Bagun, a rugged subdistrict far inland in Borneo, where indigenous dayaks live in villages clinging to the banks of fast-flowing rivers. But First Resources didn’t have any subsidiaries anywhere near there. Instead, he was working for FAP Agri. “I was confused,” he told us. "How come I wasn’t placed in First Resources? Why am I in a Fangiono group plantation?”

FAP Agri was part of First Resources, his manager reassured him.

Lambok was one of six former employees The Gecko Project interviewed who were trained at the centre, between 2011 and 2018, but then assigned to work for FAP Agri or another group that they knew as New Borneo Agri. Some were sent to the shadow companies directly from their training; others were sent to work at First Resources first, before they were moved to the other groups.

The companies that fell under the umbrella of New Borneo Agri were those owned, on paper, by Sulaidy—the Sulaidy group.

At both FAP Agri and New Borneo Agri, the trappings of corporate life repeatedly pointed to First Resources. One former employee said he was given a First Resources uniform, while working for FAP Agri; initially, at least, FAP Agri flew First Resources flags. Employees at New Borneo Agri and FAP Agri described opening their IT systems, only to find that it was clearly operated by First Resources; and being given document templates with the firm’s logo.

There was also a more creative way in which the company would instil a sense of corporate culture. “We used to sing [the] First Resources [song] every morning,” said Lambok of his time at FAP Agri.

Joko, who worked for both First Resources and FAP Agri, said they would be asked to sing it when guests visited, or when bonuses were handed out. He described it as being like the company’s Pancasila, the foundational philosophy of the Indonesian nation, extolling the virtues of loyalty, integrity, perseverance, endurance and care for others.

We are the First Resources group, determined to excel in agribusiness.

With our loyalty growing, we are proud to be part of you.

We uphold integrity. One word with deed.

The boundaries between subsidiaries assigned to First Resources, FAP Agri or New Borneo Agri, on paper, were fluid in practice. Staff who worked on the plantations for several years found themselves routinely moved between them.

One said when he was moved to PT Palmdale, a plantation company in West Kalimantan, his manager told him that it was a part of New Borneo Agri. On another occasion he was moved to another firm in East Kalimantan. “Even now I don't know, at [that subsidiary] whether I joined First Resources, or FAP, or Borneo Agri,” he said. Corporate records show it was a FAP Agri company. “It’s just one big group,” he added. “We were taught that way. That it’s all part of First Resources.”

The staff from the different companies could meet and compare notes at annual “kick-off” meetings. Three employees said they were brought together to present their achievements and set targets for the coming year, with subsidiaries in their province from First Resources, FAP Agri and New Borneo Agri.

The divisions between the groups were even less apparent in the regional office in Balikpapan, in East Kalimantan province, where analysts crunched spatial and production data. Though the analysts were assigned to work on specific companies, they routinely jumped across to help out as the work demanded.

"It’s just one big group. We were taught that way. That it’s all part of First Resources.”

“At the beginning it was clear that I was recruited by First Resources, so you can confirm that we are in First Resources,” said one employee. “[But] for those in Balikpapan, it's a bit more complicated. I didn’t really understand where I worked sometimes. It was mixed-up, you know, between First Resources, New Borneo Agri, FAP Agri.”

Some of the employees had access to meetings at which significant budget decisions were made, they said. Those meetings would cover the operations of both First Resources and FAP Agri. Assistants from both companies would collect data from the mapping teams and combine it so they could develop a budget for the following year. Cecep, who worked for New Borneo Agri, said he attended a budget meeting held at First Resources’ Balikpapan office. “People from FAP, people from Borneo Agri there, in one room,” said Ujang, who also observed these meetings. “And there is only one person in charge: Mr. Akiong.”

Akiong is the alias of Lau Cong Kiong, who made an appearance at Martias’ corruption trial more than a decade ago, at which he was described as an accountant for four of the companies involved in the logging scam. A paper trail, later picked up by the activists, shows him working his way through the family business seamlessly since then. To Ujang and his colleagues, he was the managing director who oversaw their operations in East Kalimantan, whether they worked for First Resources, FAP Agri or New Borneo Agri.

“There was only one boss,” said Ujang of Lau Cong Kiong. “He gave instructions to everyone. That means not just those in First Resources. He ruled over Borneo Agri too.”

Three employees said they had experience of him overseeing First Resources, New Borneo Agri and FAP Agri; five others that he had played that role for First Resources and FAP Agri. The employees who came into contact with Lau Cong Kiong said he was a tough manager, but gave flattering accounts of his character — he was calm, quiet and even humorous. “For me, he is a good person,” said Joko. “He shares knowledge, he’s nurturing.”

Two employees placed in West Kalimantan said that another man, named Lion Sanjaya, played the same role in that province. Lamhot said that Lion was a consistent presence, whether he was working for subsidiaries of First Resources or New Borneo Agri. “In West Kalimantan, if we meet the boss, it’s Pak Lion, wherever our plantation is,” he said. The account is supported by Lion’s LinkedIn profile, which formerly stated that he was concurrently an executive for both First Resources and FAP Agri. (Lau Cong Kiong and Lion Sanjaya did not respond to requests for comment).

But the managing directors were not top of the food chain. That privilege belonged to the Fangiono brothers: Ciliandra and Cik Sigih, who would visit the plantations three times a year. This gave plantation-level employees regular access to the company’s most senior executives. Former employees recalled meeting both brothers at subsidiaries assigned to First Resources, FAP Agri and New Borneo Agri.

Lamhot said they would receive a circular letter notifying them that the brothers were scheduled to visit. They would have to prepare data for them to review and make sure the plantations were in good condition. “We wouldn’t sleep for a week,” he said. “Because if there was the slightest mistake we would have been fired.”

According to Ujang, the workers were so afraid of being fired if they made a mistake that they would skip church or the mosque. “That’s why we used to say, they were more afraid of the owner coming than God,” he added.

The brothers would arrive by helicopter. The workers lined up to greet them, before they were escorted to inspect plantations.

Employees placed the brothers at at least two specific New Borneo Agri plantations. One recounted seeing Ciliandra make at least one and Cik Sigih several visits to PT Palmdale, one of the shadow companies in West Kalimantan, in 2017 and 2018. Ujang recalled Cik Sigih’s helicopter landing in a First Resources concession, before he was driven to visit New Borneo Agri, to review the implementation of a project.

Cik Sigih was a more regular visitor than his older brother, Ciliandra. Ciliandra would ask fewer questions of them, and tended to focus on finances. Cik Sigih — gym fit and stern — was more interested in ensuring the plantations were up to scratch. He was tougher on the employees. Ujang speculated that this was because Cik Sigih wanted to prove to his father that he could handle the job. “It's like he wants to prove to his father, you know, 'I can do this’,” he said. “The way to prove it is to pile on pressure.”

While the employees were clear that the brothers were in charge of the family firm, their father remained a lingering presence. Though First Resources had insisted Martias ceased to be involved in the company in 2003, Joko recalled him visiting East Kalimantan in late 2016 or early 2017, along with Cik Sigih and Lau Cong Kiong. They met in a saung, a kind of hut within the plantation, where he “told stories” and sought to motivate the staff.

“It's like he wants to prove to his father, you know, 'I can do this’. The way to prove it is to pile on pressure.”

Another employee said he was frequently shown motivational videos featuring Martias, when he worked at both First Resources and its shadow companies. “The video showed his story, how he managed to do [what he did],” he said. “From the beginning.”

But one employee suggested that Martias’ ongoing involvement was more than motivational. In 2019, he said, Martias took part in a teleconference to discuss FAP Agri’s annual budget. The employee described him as like a “grandfather” who was essentially retired, and just checking in on the developments in his company. Nonetheless, he discovered that Martias was expected to sign off on the budget.

“I scrolled down to the bottom of the document and the total budget was written right there,” he said. There were two names to sign the final approval — Ciliandra and Martias. “He needed to sign the document as well. His name was right there.”

Martias did not respond to requests for comment.

The ebb and flow of deforestation

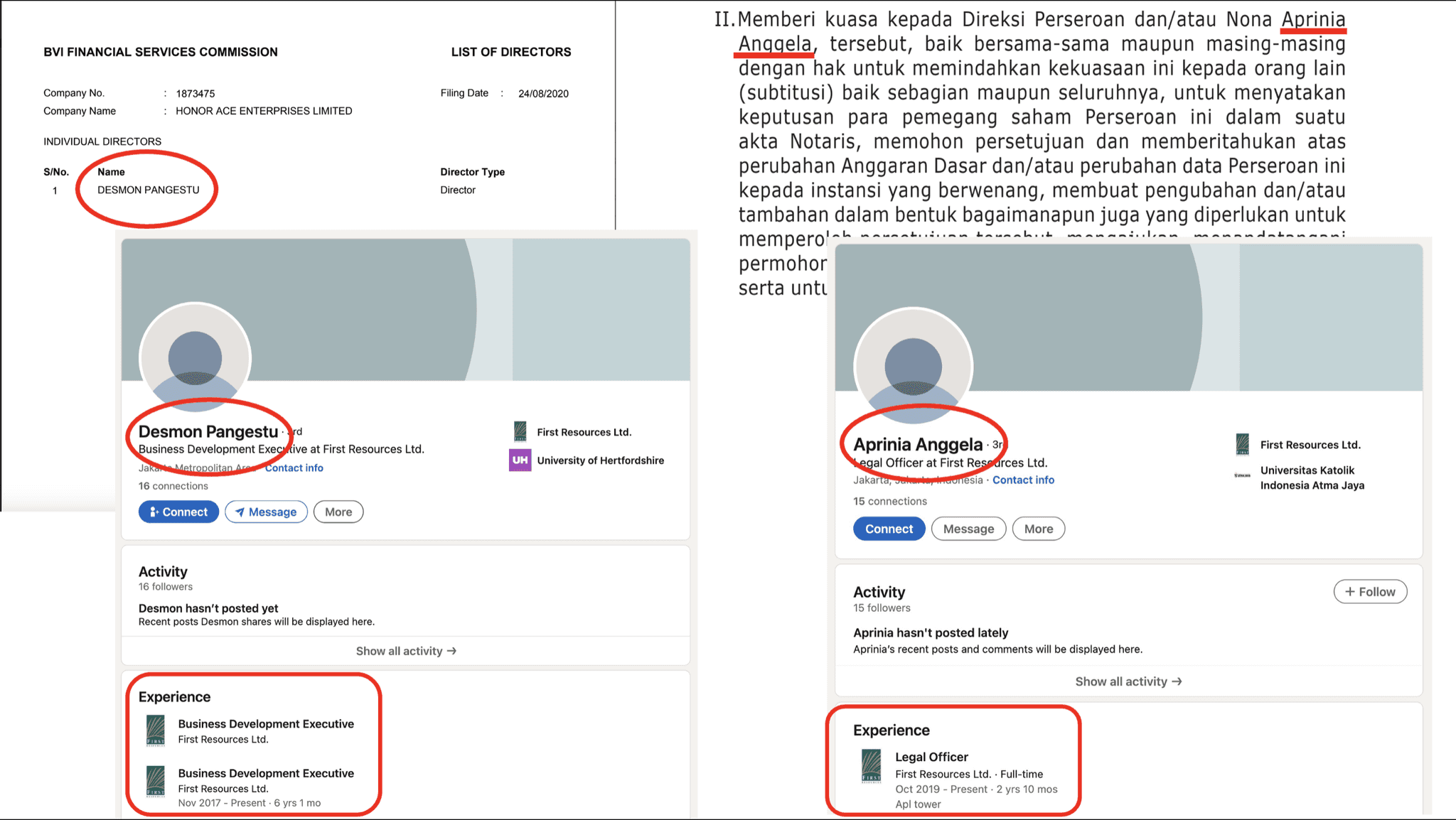

Documents obtained by The Gecko Project provide evidence in support of the case that the Fangionos are New Borneo Agri's ultimate beneficial owners. In 2017, a firm called Honor Ace Enterprises Limited took control of the companies that form New Borneo Agri, supplanting Sulaidy as the majority shareholder. Honor Ace is registered in the British Virgin Islands, a secrecy jurisdiction that does not disclose companies’ shareholders.

However, a string of legal documents show that in 2019, a woman named Aprinia Anggela was granted authority to act as the representative of these shareholders. At the time the documents were signed Aprinia was working as a legal officer for First Resources, according to her LinkedIn profile.

Among the scant information the BVI authorities do make available is the sole registered director of Honor Ace. As of October 2023, it was a man named Desmon Pangestu. Desmon, like Aprinia, is employed by First Resources. A notice in Indonesia's newspaper of record, Kompas, shows that Desmon is also Martias’ nephew — a member of the Fangiono family.

If the question is not who owns the New Borneo Agri companies on paper but — as in Martias’ 2007 corruption case — who controls them, the evidence seen by The Gecko Project points squarely at First Resources. No one formally associated with the New Borneo Agri companies, including Desmon, Aprinia, the shareholders of Honor Ace Enterprises, and Sulaidy himself, responded to requests for comment.

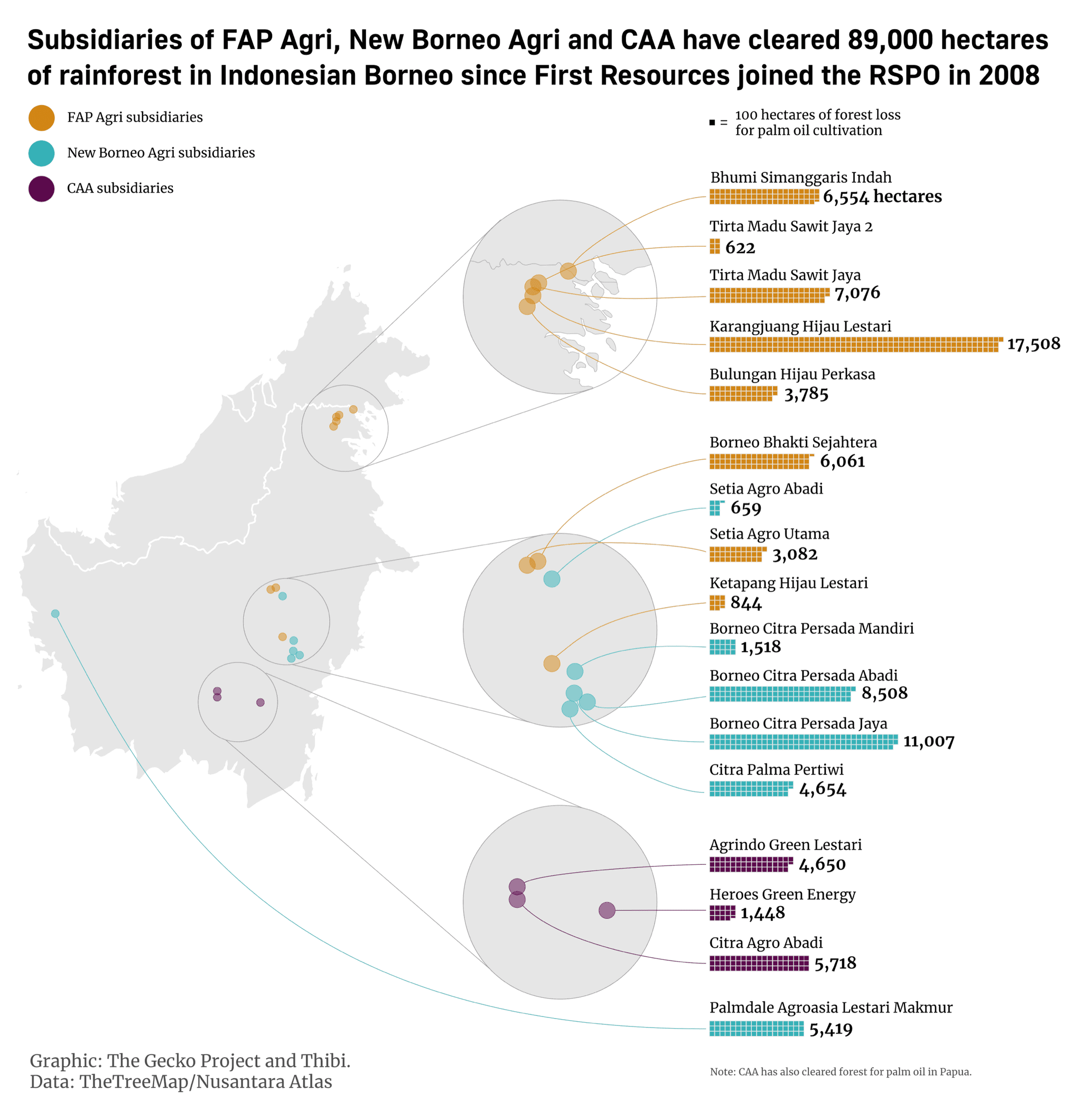

The ebb and flow of deforestation that could be attributed to the companies controlled by the Fangionos illustrates how they collectively enabled the family to keep expanding their plantations without restraint, even as they signed up to increasingly stringent sustainability commitments.

When First Resources joined the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, it brought a degree of respect and market access, but also restrictions — it would now be far harder for the firm to clear forests. The same year, deforestation by FAP Agri spiked, growing from just a few hundred hectares to more than 8,000 hectares. The next year it nearly doubled again.

Then, in 2015, First Resources adopted a zero deforestation policy. The very same year, New Borneo Agri kicked into life, and the companies organised under this new shadow group cleared 4,000 hectares of rainforest.

The consequence is that companies allegedly controlled by the Fangiono family, in addition to First Resources, have cleared more than 95,000 hectares of forest — an area more than 15 times the size of Manhattan — in the years since First Resources committed to abide by the rules of the RSPO.

Our investigation was unable to establish the same functional overlaps between CAA and First Resources as the other groups. The three former employees we interviewed who worked for CAA did not work for the other groups, and those who did work for First Resources, New Borneo Agri and FAP Agri did not circulate into CAA in the same way they did among each other. That may at least partially be explained by geography: three of the companies operate in the same provinces, in some cases adjacent to one another. CAA’s operations are concentrated in two other provinces, one of which is some 2,000 kilometres away from First Resources’ Borneo operations.

CAA did not respond to a request for comment. Ricky Tjandra, president director of FAP Agri, repudiated the findings of our investigation. “FAPA has no relationship as a subsidiary or financial, legal and operational relationship with First Resources, Cilandry Anky Abadi or the Sulaidy Group,” he wrote.

The RSPO has had an opportunity to probe the connections between all the groups since at least 2021, when an anonymous party lodged a complaint alleging that First Resources, CAA and FAP Agri — though not the Sulaidy Group — were functionally the same thing. After two years of procrastination, the body is commissioning an independent investigation into the claims.

Sangeetha Umakanthan, deputy director of communications for the RSPO, defended the length of time it has taken on the grounds the case involves “complex allegations which need careful determination.” She said it would be “challenging” to specify when it might be resolved, and declined to comment on the possible consequences if the organisation decides in favour of the complainants.

According to the RSPO’s rules, those consequences could be considerable. First Resources could be required to pay substantial compensation for the rainforest it has cleared, and be brought to the table over land conflicts between Dayak communities and shadow companies. Buyers may also baulk at the idea of continuing to trade with a company that has systematically deceived them for a decade.

“We need to hold these huge palm oil groups to account,” said Angus MacInnes, the FPP researcher. “They can't just have one arm of their operations that sign up to all these human rights standards, sustainability standards, zero deforestation and all of that. But then have this other arm of their business, which is basically completely unaccountable and involved in really egregious human rights violations.”

The case could build momentum for a wider reckoning over the use of these practices. Many of the family-run firms that dominate the oil palm and timber sectors in Indonesia have been the subject of credible allegations they are running extensive shadow company networks, while remaining members of industry sustainability schemes.

Earlier this year, a group of organisations attempted to untangle who is behind a company clearing orangutan habitat in Borneo and constructing a giant new mill that threatens to suck in vast areas of rainforest.

While the ultimate owner is hidden within a secrecy jurisdiction, a web of overlapping addresses, staff and shareholders point to the Tanotos, one of Indonesia’s wealthiest families, whose Royal Golden Eagle conglomerate proudly boasts of its sustainability credentials and zero deforestation policy. RGE denied there was a connection.

In a wood-panelled room in the Canadian parliament, in May this year, legislators grilled executives from a company named Paper Excellence over allegations that it was secretly controlled by the conglomerate Sinar Mas. An investigation led by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists had unearthed evidence that the two firms had been “secretly coordinating” and found that the people behind Paper Excellence “appear to have a pattern of using thickets of corporations, including in tax havens, effectively shielding transactions and assets from public and government scrutiny.”

Paper Excellence’s executives claimed that its owner, Jackson Widjaja, a scion of the family behind Sinar Mas, was operating it independently and denied that he was acting as a front for the family firm.

The billionaire families behind these conglomerates — the Fangionos, Tanotos and Widjajas — have remained steadfast in their denials, even as the evidence mounts that they have sought to hide swathes of their growing empires. The cycle of allegation and denial, as activists and journalists untie the knots of their complex structures, has done little to dent their reputation among many of their buyers. Or, perhaps, provided a veneer of plausible deniability.

Procter & Gamble and PepsiCo were among the consumer goods firms that were sourcing palm oil from First Resources in 2018, when Greenpeace first published extensive allegations relating to the Fangionos’ shadow companies. Supply chain data published by both firms shows that First Resources continues to supply them now. PepsiCo did not respond to a request to comment on our findings, while Procter & Gamble declined to comment.

“Perhaps they’re worried what they might find.” Angus MacInnes, Forest Peoples Programme

Two other companies that have continued to source palm oil from First Resources were more forthcoming. Cargill wrote that it took the allegations “very seriously,” had “initiated an investigation into their validity” and would take “immediate action” if First Resources had violated its policies.

Colgate-Palmolive noted that its suppliers — who buy palm oil from First Resources and sell it to Colgate-Palmolive — had previously received denials from First Resources over its links to shadow companies. But it said it had “re-engaged” with these suppliers in light of the new evidence from our investigation. Colgate-Palmolive also said that it was asking its suppliers to push the RSPO for a “timely ruling” on the complaint.

Whether the RSPO’s investigation into the Fangionos will pull back the veneer is questionable. The Sulaidy group was not included in the complaint lodged with the RSPO. The Fangionos have displayed a propensity for shape-shifting that may muddy the waters. Several employees recounted how the company had taken steps to create greater distinctions between FAP Agri and First Resources — removing First Resources flags, stopping singing the song, and moving offices. Three suggested that New Borneo Agri, meanwhile, had been rebranded as Kalimantan Agro Sejahtera.

MacInnes, of FPP, made the case that the companies buying from these producers had to play a “more proactive role” in investigating the murky networks of shadow companies linked to their suppliers. “Perhaps they’re worried what they might find,” he said. “Because it would be pretty ugly. And require some pretty fundamental structural changes to the way they run their businesses.”

Read more reporting from The Gecko Project on corporate accountability here.

Join The Gecko Project's mailing list to get updates whenever we publish a new investigation.

****

Reporting by Margareth Aritonang, Alon Aviram, Antonia Cundy, Johanes Hutabarat, Tomasz Johnson, Tom Walker.

Editing by Peter Guest, Tomasz Johnson.

Header illustration by Chuan Ming Ong. Charts by Thibi.

Videos of trucks carrying palm oil by Jamie Wolfeld/Forest Peoples Programme. Videos of deforested land in East Kalimantan by Pradarma Rupang.