- A long-serving government minister facilitated encroachment on a national park in Sierra Leone, enabling political elites to construct luxury homes inside its borders.

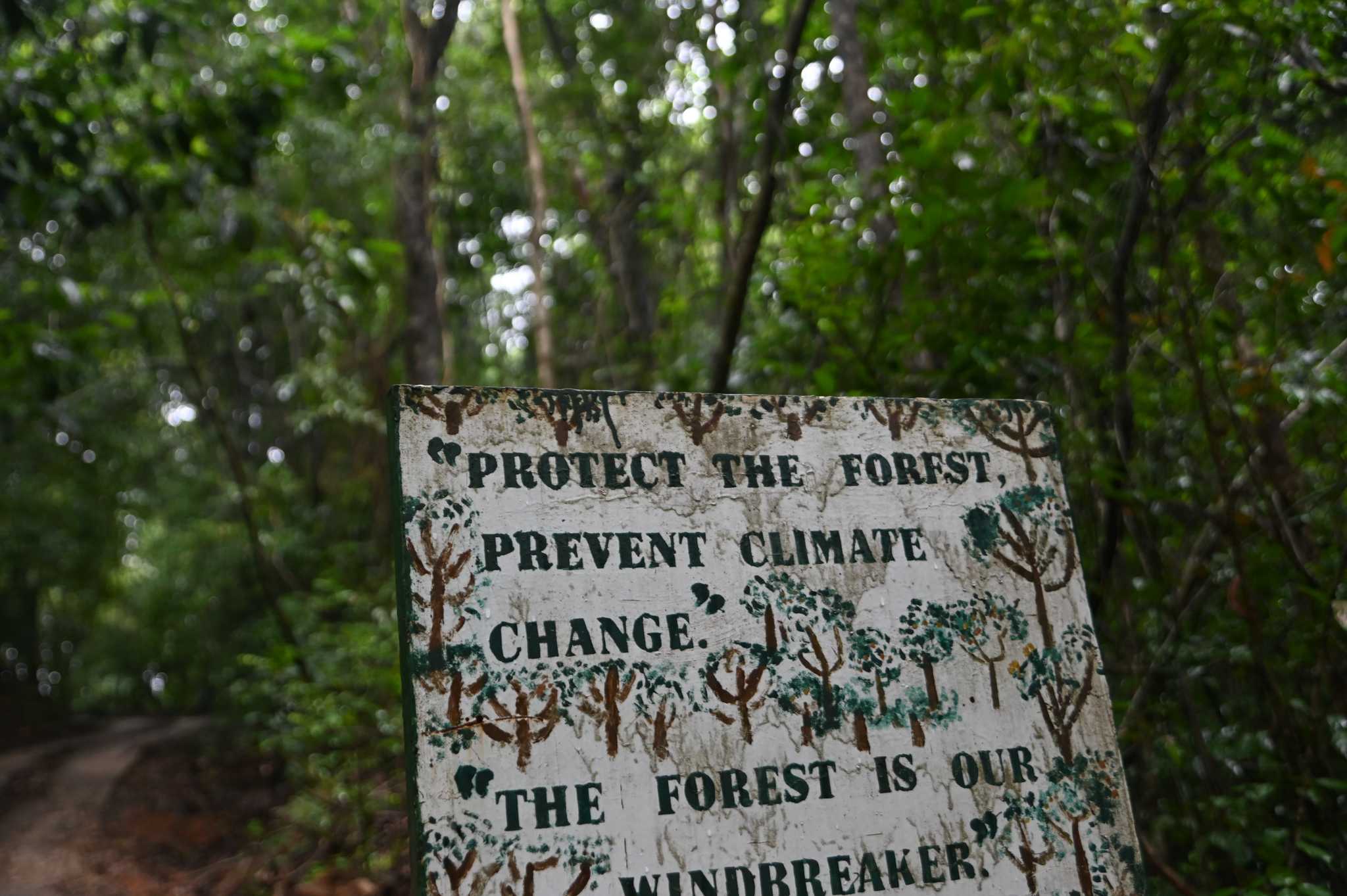

- The park is home to chimpanzees and has been proposed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but is threatened by rampant deforestation.

- An investigation launched by the president in 2022 revealed the role of the minister. But four years on, he remains in office and homes are still under construction. The results of that investigation were buried — until now.

- This article is part of a series on the disappearing forests of West Africa, supported by the Pulitzer Center.

With their multiple storeys, columns and arches, the mansions under construction in Bio Barray are a world away from the shanty towns of nearby Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone.

The neighbourhood is host to a growing number of homes long rumoured to belong to the elite of this West African country, with dozens sprouting up in the past five years. Behind it lie rainforested hills. Nearby, a beach so picturesque it was once the setting for a Bounty chocolate bar advert.

Locals say Bio Barray is named after Sierra Leone’s president, Julius Bio. Far from being a badge of honour for the president, however, the settlement now emerges as an emblem of environmental crime, impunity and alleged corruption that are destroying a national park and threaten a major dam.

The mansions lie inside the Western Area Peninsula National Park, a mountainous landscape home to wild chimpanzees that the Sierra Leonean government has proposed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. At least 50 illegal houses have been built or are under construction within park boundaries in Bio Barray, on land that was covered in rainforest as recently as 2019.

In 2022, President Bio launched an investigation to discover how the illegal encroachment had taken place and the impacts of the deforestation it had contributed to. But its full findings were never made public.

The Gecko Project and The Associated Press obtained a copy of the report that arose from that investigation. It points to the involvement of a long-serving minister and other officials in corruptly providing land ownership documents to the new residents. It branded the deforestation of the park “an environmental time bomb that has to be nipped in the bud”.

Our own investigation confirms that some of Sierra Leone’s most powerful and well-connected people, including a senior diplomat and a general, are among those with homes in the settlement. Those homes remain standing, more than two years after the report was handed to the president.

“[The] government is fully aware of what is going on,” said Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr, the mayor of Freetown and an environmentalist, who intends to challenge Bio for the presidency at the next election.

She said the settlement was home to the powerful individuals who were allowed to ignore the law. “They are being given permission, simple,” she added.

Multiple other sources interviewed for this story agreed Bio Barray had become an enclave for political elites. Isata Mahoi, a government minister who was a member of the investigative team, said “it must be people who are connected and have some influence in power.”

Sierra Leone’s sweltering, frenetic capital is sandwiched on a strip of land between the rolling Atlantic and the mountains of the national park.

A decade ago, rainforested hills ran for 15 miles down this coastline. Now, many seaward slopes have been stripped barren by landgrabbers, charcoal burners, cannabis farmers and miners.

Since 2012, a third of the forest in the park has been destroyed or “significantly degraded”, according to an assessment by the World Food Programme (WFP), which has published reports on deforestation as part of its remit to prevent disasters. That amounts to an area 18 times the size of Central Park.

The rate of forest loss has remained stubbornly high. Satellite data gathered by NASA suggests there were 220 fires within the park boundaries in 2024, which the WFP believes were mostly set deliberately.

About a mile from Bio Barray, the Guma Dam cradles a reservoir providing 90 per cent of the water for Freetown’s 1.4 million inhabitants. The government investigation found that deforestation and other human activities in the national park could lead to a “water shortage crisis” in Freetown, which it described as a “looming disaster”.

The threat of landslides looms large in the minds of the city’s residents, after deforestation and torrential rain caused a slip on the edge of the national park that killed more than 1,000 people in 2017.

Maada Kpenge, managing director of Guma Valley Water Company until October, said that one day the dam will “inevitably” fail, and called development beneath it “really dangerous.”

The report noted that if the dam were to fail, the residents of Bio Barray would be “wiped out.” “It will flow down very quickly,” Kpenge said. “If you find yourself there, you will not be able to escape.”

Just inside the park boundaries, Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary, where rescued primates are rehabilitated, is among the country’s leading tourist attractions. But it too is threatened by landgrabbers and fires, according to its founder, Sri Lankan national Bala Amarasekaran.

Amarasekaran described the deforestation as “alarming”, with illegal developments bearing down upon the sanctuary and risking landslides. “This is not an area [where] you want to poke holes in the hill to build houses,” he said. “This is like digging graves for our children.”

'A serious threat to law and order'

It was a devastating fire close to the dam in April 2022 that prompted President Bio to form a committee to delve into the encroachment on the park.

The committee comprised 13 people — including police officers, lawyers, nonprofit workers and a member of its Anti Corruption Commission (ACC), — who analysed satellite imagery, inspected documents and carried out site visits.

Their work, which can be reported in detail for the first time, aimed to discover the extent of deforestation, how permits had been secured for homes and to provide recommendations on “how such a dismal situation can be avoided in the future.”

The committee found there had been “widespread and indiscriminate clearing of forested areas” and that a ban on construction inside the park was “far from being effective.” They identified 21 settlements inside the park, mostly set up by people eking out a living in fishing, farming, tourism or mining.

The investigation focussed on four of these. The single biggest hotspot for encroachment on the park was around Bio Barray, where deforestation had “increased exponentially” in the months leading up to the investigation, “threatening the integrity of the dam itself”.

“It is safe to suggest that security personnel deployed to enforce the ban have either been compromised or are complacent,” the committee wrote.

Officials at the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Country Planning knew “vast stretches" of state land were being unlawfully occupied, but were “reluctant to act robustly for reasons unknown,” the investigation found. It was described as a “serious threat to law and order.”

The committee found that “certain State actors were not only complicit in the encroachment process but they encouraged it and even went as far as facilitating it for personal gains.” Among the “major players” they pointed to were officials at the land ministry.

Under the State Land Act the Ministry of Land can transfer state land to private individuals, a process that can be initiated simply by issuing a letter. Ministry officials used this power to hand out plots of land in Bio Barray, despite the fact it was inside the national park where clearing and construction is illegal under the Forestry Law, according to the report.

The Minister of Lands, Housing and Country Planning at the time was Denis Sandy. Sandy has been trailed by multiple allegations of wrongdoing in recent years, including corruption, sexually abusing his stepdaughter and fabricating a certificate to procure a divorce. In a civil case, Sandy was found by the Sierra Leonean courts to have unlawfully seized a man’s property with the aid of a rogue reverend using forged documents. He has not been convicted of any crime.

Sandy personally signed at least 175 documents granting land to private individuals, the committee found. It accused his ministry of “institutional lapses” and said “due processes were not followed,” the department failing in its “core mandate” by letting encroachers into the greenbelt “effortlessly.”

The committee recommended “punitive measures” against ministers and 16 other named officials. The authors wrote, “There is [an] urgent need for [the] government to reclaim all lands occupied in the greenbelt by private citizens.”

The report singled out the land minister by name. “In the opinion of the Committee, certain public officials like Dr Dennis Sandi [sic] must be brought to book for flagrant violation of laws aimed at protecting the greenbelt with impunity,” they wrote.

Sandy did not respond to requests for comment.

Investigation? What investigation?

The report appears to have been delivered to Sierra Leone’s then chief minister, who liaises between the president and government bodies, in September 2022.

A full year later, the president’s office published a photo of President Bio officially receiving it from one of the commission’s co-chairs. The accompanying press release said that “people in high places” were involved in deforestation, without detailing the serious allegations against Sandy and other officials.

“I have been waiting for this report and we will act on it very soon and do whatever is needed to be done,” President Bio said.

But the homes in Bio Barray remained standing — and construction continued, analysis of satellite imagery shows. Several new large buildings cropped up in the months after the chief minister reportedly received the report and many had roofs installed in the months after the president pledged to act upon it.

Notably, although Sandy was removed from the department in a 2021 reshuffle, he was simply shifted into another cabinet role and now serves as Minister of Works and Public Assets.

In a WhatsApp interview this November, the current chief minister David Sengeh — who took office in 2023, after the report says it was handed to his predecessor — insisted various government departments and agencies had acted on the report’s findings. He would not say whether any punishments had been signed off by cabinet, as prescribed.

“Cabinet discussions are not public,” he said.

Asked why Sandy had been allowed to remain a minister, Sengeh said, “I don’t think government makes decisions based on accusations only.”

Sengeh said that the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) was the appropriate body to investigate the allegations. “I'm sure the competent body, which is the ACC, will be the one who will look into that,” he said when presented with the allegations against Sandy.

A member of the ACC had been included as part of the panel that carried out the investigation. But in a phone interview, its head, Ben Kaifala, appointed in 2018, said no investigation into the case had been launched and denied ever seeing the report.

After being read the section of the report detailing Sandy’s alleged central role and the report’s conclusion that officials had “facilitated” encroachment on the park for “personal gains”, Kaifala questioned whether it was a case for the ACC.

“Everybody in a public position facilitates something,” he said. “But is the facilitation induced because they are [motivated] by private gain? The real challenge I have is that I have not seen this report.”

But he insisted the ACC would “look at” the report now that he had been alerted to it. “If there is evidence, I can assure you we will act on it,” he added.

Kaifala noted that it was the role of other government agencies to protect national parks. “Other institutions must do their job,” he said. “I can’t do it for them.”

He confirmed the ACC had previously looked into Sandy and he was still under investigation in an unrelated case.

Another high-ranking official who says he was unaware of the report was Thomas Kamara, executive director of the National Protected Area Authority (NPAA).

The committee found that the NPAA — under Kamara’s predecessor — “undeniably aided” the “institutional failure” of the land ministry and “cannot be absolved of blame” for construction in the national park. NPAA staff were accused by other officials of being “involved in sale of lands within the green belt.”

Kamara was appointed in November 2023, two months after the completed investigation was publicly handed to the president. In a phone interview he denied knowledge of the report, “I have no idea what the result was or what the findings were,” he said.

But he claimed that all encroachment on the park had been stopped. Responding to the allegations in the report about NPAA staff, he said he had “no evidence” of them being involved in land deals. “What you are referencing is the past, if ever that was the case,” he added.

In mid-2025, President Bio claimed that nobody is above the law when it comes to illegally selling state land, commenting on allegations that judges and MPs had been involved in the practice. He has also said of illegal homes in the greenbelt, “Even if a house belongs to me or my family, it would be broken down.”

Bio initially agreed to an interview, but would not commit to a date and then did not respond to requests for comment.

News reports in the local media suggest some homes inside the park have been demolished. When a reporting team visited the parts of Bio Barray that fell inside the national park, however, there was no evidence of any evictions. Builders remained hard at work completing homes.

Aki-Sawyerr, the mayor of Freetown, branded the investigation a “cynical” attempt by the president to present the appearance that he was addressing the encroachment. “It's just done so that, you know, the international community will know, ‘Oh, yeah, he's taking action,’” she said. “Nonsense.”

Isata Mahoi was on the investigative panel, then working for a peacebuilding nonprofit. She’s since been made Sierra Leone’s Minister for Gender and Children’s Affairs. During an interview in an upmarket Freetown hotel, Mahoi said Sandy, now her colleague, would, “definitely have to take the blame.”

“The report is very clear,” she said. “And that is our recommendation.”

Asked why Sandy was still a minister, she replied, “It’s very tricky and I’m not sure I have an answer to that particular question.”

Another of the investigative report’s authors, speaking anonymously for fear of repercussions, made the case that Sandy’s actions must have been motivated by corruption.

“Favours are given to the minister,” they said. “There is no other explanation you can give.”

They agreed ACC commissioner Ben Kaifala should have a file on the case, adding, “This should be of concern to every Sierra Leonean.”

The committee member concurred that senior army and government officials lived in Bio Barray. “That was the situation exactly,” they said. “They have been compromised.”

'The big boys'

In Freetown, rumours swirl around the identity of the owners behind Bio Barray’s mansions.

The investigative report did not name individuals with homes in Bio Barray. It identified 876 landowners within the national park, but only 301 came forward in response to a request for documents attesting to their land claims.

Elites held property in Bio Barray through proxies, to disguise their beneficial ownership, according to the anonymous report author. When investigators demanded all supposed landowners provide their title deeds, “the big boys did not come,” they said.

A door-to-door survey of 46 villas carried out by this reporting team supported the case that Bio Barray has become an enclave for elites. Some 14 owners worked in government jobs, according to residents, caretakers and security guards looking after the premises. They included officials reportedly working in the Office of the President, the land ministry and the Environment Protection Agency. Another three had military backgrounds and one was a serving police officer, local people said.

The Gecko Project identified the owner of a half-built villa inside park boundaries, featuring balconies and four columns supporting a two-storey portico, as one of Sierra Leone’s top diplomats. Denis Sandy had personally signed documents offering him a lease to the land.

Another mansion under construction, fronted by a two-storey rotunda, was identified as belonging to a general in the Sierra Leonean Army.

Legal analyses by two separate Sierra Leonean law firms commissioned for this investigation concluded that Sandy did not have the legal power to grant leases for land within the park. One said they were rendered “invalid and of no legal effect”. Without written permission from the Minister of Environment, building the houses was illegal too, the firm found.

When the reporting team rang Foday Jaward — who was environment minister from 2018 to 2023 — he emphatically denied ever signing documents giving permission for the properties.

Meanwhile, at Tacugama Chimpanzee Sanctuary, rangers nervously watch the deforestation line creep closer to their perimeter. Weeks before the reporting team visited a wild chimp was caught on a camera trap right outside the sanctuary, and they have previously impregnated female chimps through the fences.

“This is their home,” said Amarasekaran, looking around the shrinking rainforest. “Give it another five, six years, if the trend continues, there won’t be a single chimpanzee in this reserve.”

Read more reporting from The Gecko Project on The Politics of Deforestation.

Join The Gecko Project's mailing list to get updates whenever we publish a new investigation.

Reporting by Ed Davey

Editing by Tomasz Johnson

Fact-checking by Tomasz Johnson

Header Image shows homes under construction in Bio Barray, inside the borders of the Western Area Peninsula National Park. By Misper Apawu/The Associated Press.