- An investigation by The Gecko Project, BBC News and Mongabay estimates that Indonesian villagers are losing hundreds of millions of dollars each year because palm oil producers are failing to comply with regulations requiring them to share their plantations with communities.

- The ‘plasma’ scheme was intended to lift communities out of poverty. But it has become a major source of unrest across the country, as government interventions fail to compel companies to deliver on their commitments and legal obligations.

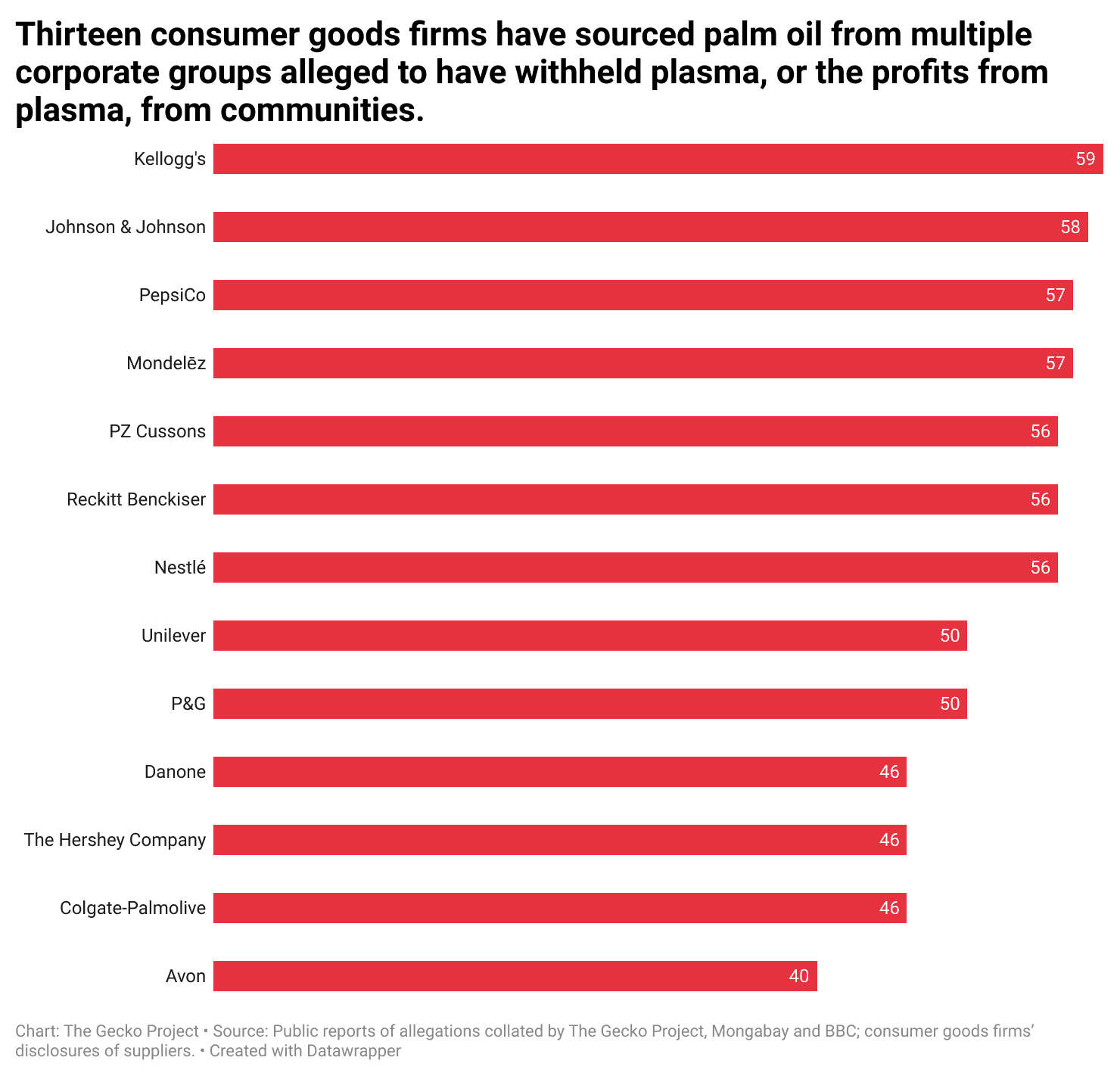

- Palm oil from companies accused of withholding profits from communities is flowing into the supply chains of major consumer goods firms like Kellogg’s and Johnson & Johnson. Some have pledged to investigate.

Part 1: ‘They took everything’

When the indigenous villagers of Tebing Tinggi agreed to give control of their ancestral land to a palm oil company in 1995, it promised to transform their fortunes.

The Suku Anak Dalam were subsistence farmers, gathering fruit and hunting game in the rainforest. The deal could give them a cut of a lucrative industry that was expanding rapidly across the island of Sumatra, in Indonesia.

The company, London Sumatra, would take control of the community’s land. In return, according to the Suku Anak Dalam, they were told they would get more than half of it back, planted with oil palms, a wonder crop whose oil was in rising demand across the globe. It would be a win-win, as the Suku Anak Dalam would sell the fruit they harvested to the company.

“The promise was a lie,” Mat Yadi, a Suku Anak Dalam leader, told us recently. “Nothing was returned to us. They took everything.”

Over a quarter century, London Sumatra’s oil palms grew tall and the bright-orange fruit flooded into its mill, producing millions of dollars’ worth of edible oil. But the Suku Anak Dalam never received the smallholdings they say they were promised. They lost not only the expected profits from the oil palm, but their land too.

By 2022, many of the tribe were living in makeshift huts inside a plantation, scraping together what income they could by picking up fruitlets that dropped to the ground when bunches of palm fruit were harvested.

The experience of the Suku Anak Dalam is not an outlier.

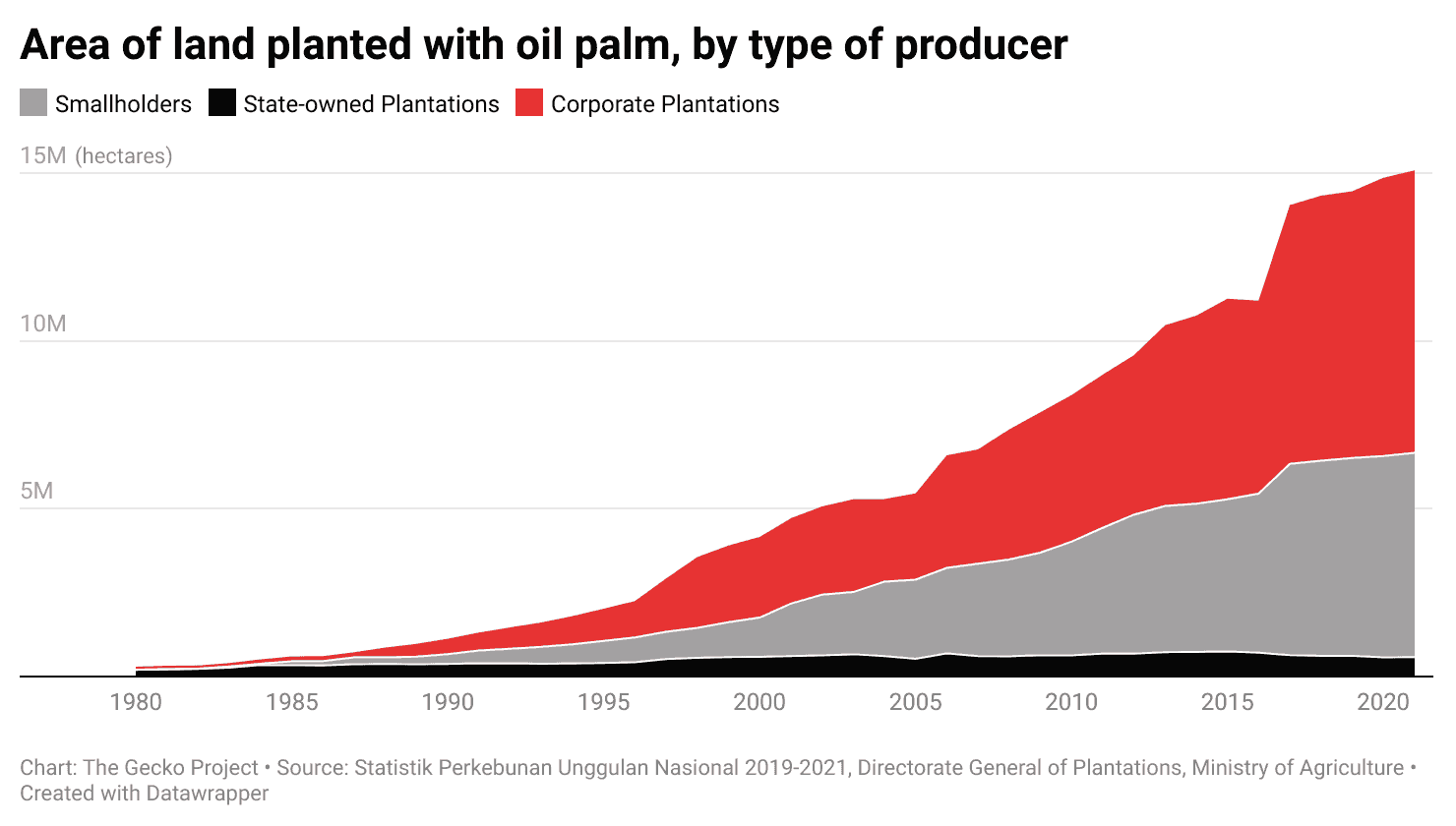

Smallholdings have formed an integral part of Indonesia’s palm oil sector since the 1980s. Private companies often promised to share a proportion of their plantation with villagers, in plots widely known as “plasma”, to gain local support and access government financing. In 2007, providing plasma became legally mandatory, with companies required to give a fifth of any new plantation to communities.

Where the scheme worked, it helped lift rural communities out of poverty, giving them their own stake in an industry worth more than $50 billion each year globally.

But for many thousands of Indonesian families, the plasma never appeared. An investigation by The Gecko Project, Mongabay and BBC News found that Indonesian communities could be losing hundreds of millions of dollars each year because the profits from plantations are flowing to conglomerates instead of them.

Disputes over plasma pervade the industry and have become a major source of unrest across the Indonesian archipelago. We found that subsidiaries of almost all of the largest palm oil conglomerates have been accused of reneging on promises or failing to meet legal obligations to share their plantations with communities.

The Tebing Tinggi case is “just one example — it’s happening everywhere,” said Daniel Johan, a leading member of the Indonesian parliamentary committee overseeing the agricultural sector. “The corporations are greedy.”

The warning signs that something was going wrong have been there for years. As the palm oil industry swept across Indonesia, transforming millions of hectares of land into plantations, stories of communities claiming they had been cheated became commonplace.

But the scale of the problem, and the toll it was taking on Indonesian citizens, remained unknown.

We set out to fill that void. Over the past three years, we mapped out and analysed plasma-related allegations made by communities against hundreds of plantation companies. We travelled to dozens of villages embroiled in plasma disputes with 27 different plantation companies operating on three of Indonesia's biggest islands. We pored through company reports, court records, government data, and interviewed more than 200 villagers, officials, academics, activists and company employees.

Our analysis of the best available government data paints a damning picture. It suggests companies have failed to provide hundreds of thousands of hectares of legally required plasma to communities. In one province alone, we estimated, villagers are losing more than $90 million each year.

Meanwhile many of the tycoons behind Indonesia’s top palm oil firms have become billionaires several times over. While the Suku Anak Dalam live in grinding poverty, Anthoni Salim — who controls the company now profiting from their ancestral land — has become Indonesia’s third-richest person, with an estimated $8.5 billion fortune.

Audits by two government agencies have sounded the alarm over plasma. The first, completed in 2019, found the state had failed to monitor whether companies were complying with plasma regulations. The second, in 2020, concluded that the prevailing regulations had allowed companies to “exploit” farmers participating in plasma schemes.

Despite this, our investigation found the government’s efforts to intervene in individual cases or reform the system remain limited and ineffective, allowing disputes over plasma to fester for years or even decades.

The impasse continues to cause unrest across Indonesia. Dozens of communities have turned to protest after failing to secure plasma through formal democratic channels. They have marched in the streets, massed outside government offices, blockaded roads and occupied plantations. These incidents have taken place at a rate of more than one a month, on average, over the past five years.

Protesters have faced violence at the hands of police. Some have been jailed for chaining shut palm oil company offices or setting fire to buildings.

Even Indonesia’s largest palm oil producer, Golden Agri-Resources, which has burnished its reputation through a high-profile pledge to end the "exploitation" of local communities, has failed to meet its legal obligations to provide plasma in several of its plantations, our investigation found.

In an interview, Golden Agri officials acknowledged these failings and said they “remain committed” to providing the plasma. Susanto Yang, who oversees the company’s plantations in West Kalimantan province, said they had been held up due to the complexity of establishing schemes properly. “We want it to be fast, but we also don’t want to violate procedure,” he said.

Some villagers have had to wait for well over a decade for Golden Agri to provide plasma.

Another explanation companies give for failing to provide plasma is that there is not enough suitable land, even as their own plantations sprawl across thousands of square kilometres of Indonesia.

Over the past decade, repeated exposés of palm oil producers grabbing indigenous lands and cutting down rainforests, accompanied by images of orangutans crawling from the remnants of their burned habitats, have pushed the industry to commit to reform. Most major producers and traders now claim to eschew deforestation and “exploitation” of local communities.

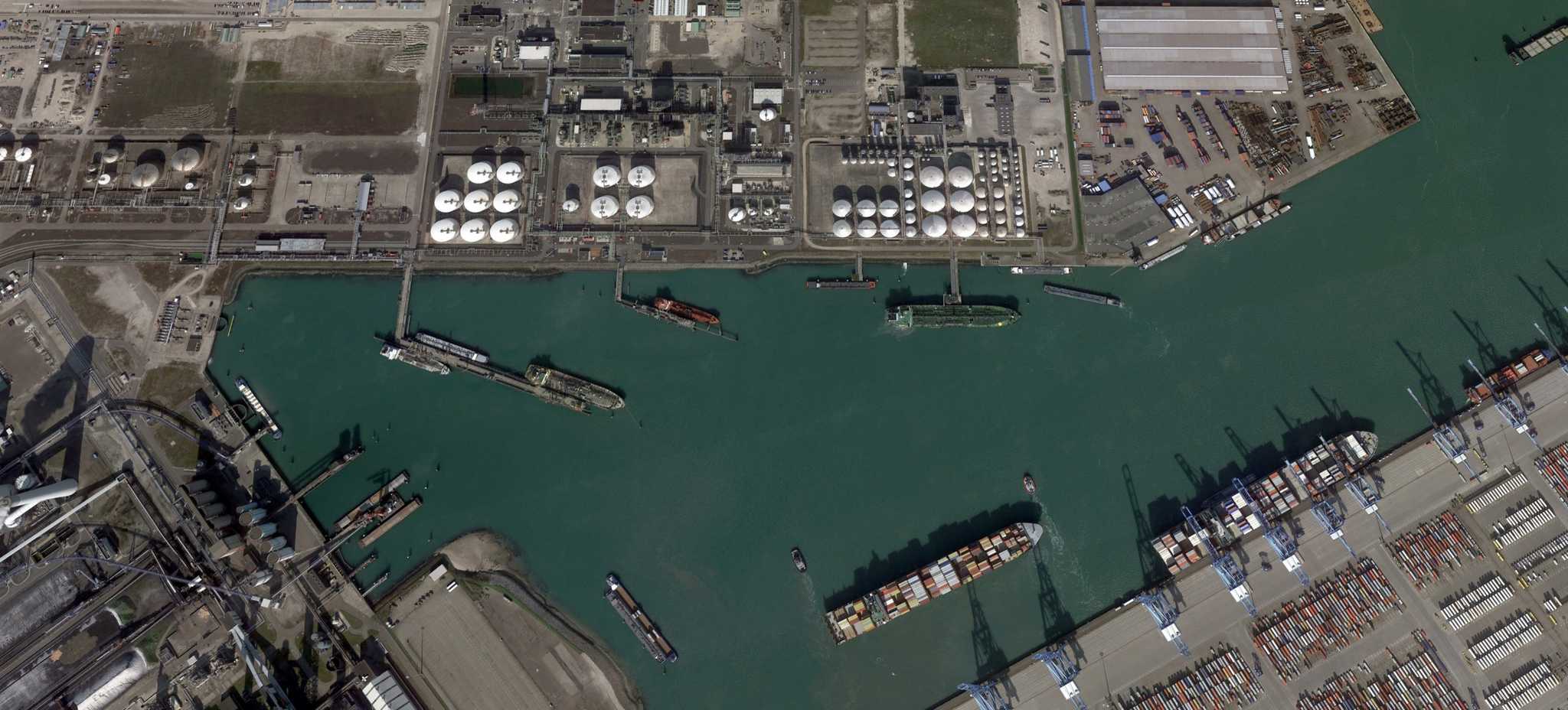

But there has been far more limited pressure on planters to ensure they are sharing profits from their operations with communities in Indonesia, where most of the commodity is produced. Because of this blind spot, palm oil tainted by this problem has flooded into the supply chains of major consumer goods firms like Kellogg’s, Nestlé and Unilever.

After being presented with a summary of our findings, six major consumer goods firms said they would take steps to find out if their suppliers have met their plasma obligations.

For now, consumer goods firms and palm oil producers continue to profit from a trade worth billions of dollars each year. For communities like the Suku Anak Dalam, the wait for the share promised to them in 1995 goes on.

“Only plasma can guarantee the survival of the Suku Anak Dalam, because their livelihoods are gone,” said Mustika Yanto, a lawyer from Tebing Tinggi. “It’s their last hope.”

Part 2: ‘A wonderful tool for poverty alleviation’

Buy something in a supermarket today and there’s a good chance it contains palm oil.

Follow that ingredient back up through the supply chain and eventually you’ll find a bright orange fruit on a palm tree, likely in Indonesia. It may be on a small plot cultivated by a farmer, or a vast plantation run by a company.

When the industry began to grow in earnest in Indonesia, in the 1980s, the idea was that a significant proportion of oil palms would be grown by smallholder farmers. Companies established plantations, but typically kept only 20 to 30 per cent for themselves. The larger portion was parcelled up into plots known as “plasma” and handed to indigenous communities and landless migrants moved in by the government from densely populated regions.

In theory, plasma could alleviate poverty while also creating a reliable labour force to work the plantations. Companies could benefit from their slice of the plantation and selling the oil that flowed from mills after the fruit was crushed.

Life on the plantations was tough. Smallholders were saddled with debt for set-up costs that ate into their profits for up to a decade and their plots were often too small to support them, according to academics who studied the early schemes. Many of the migrants sold up and returned to their home villages.

But plasma could also transform the lives of those who weathered the lean years. When the palms reached peak productivity, some farmers were earning several times the minimum wage. Once-impoverished families could now buy motorbikes, build sturdy homes and provide their children with an education.

“A well-implemented scheme will definitely contribute to poverty eradication,” said Idsert Jelsma, a consultant who has researched palm oil smallholders for more than a decade. “Plasma has been a wonderful tool in the past for helping communities. It still can be a wonderful tool.”

Over time, the government withdrew from managing plantations, tweaking the system to incentivise private investment. By the late 2000s, as the price of palm oil surged, plantations were expanding across the country at a rate of more than 300,000 hectares each year.

Some companies did simply take community lands without offering anything in return. Villagers had fragile legal rights, and firms holding government licences, sometimes backed by the police or military, could annex forests and farmlands without their consent. But it remained common practice for companies to offer smallholdings to gain local buy-in.

“That was always part of the package they were promised,” said Marcus Colchester, an activist and anthropologist with the Forest Peoples Programme who has worked with indigenous communities in Indonesia for three decades.

Through the 2000s, the government was increasingly hands-off, handing out licences but giving companies free rein to decide how best to manage plasma schemes. But it sought to ensure communities would benefit by cementing the requirement in law in 2007.

By then, the dominant model, according to industry observers, was one in which farmers played no active role in the plasma estates. Instead, the companies used paid labour to tend to the plasma, and the “smallholders” were told they could sit back and let the profits roll into their bank accounts. The rationale was that large corporations, with capital and know-how, could manage plantations more efficiently than villagers.

“The government became really neoliberal and eventually wanted to just let the plantation companies more or less run the show,” said Lesley Potter, a visiting fellow at Australian National University whose research has focused on Indonesian smallholders.

“And of course, the plantation companies were quite keen to run the show, until they decided it was a good idea to get rid of the smallholders.”

Part 3: A decade of protests

By January 2017, the Suku Anak Dalam had been waiting more than two decades for London Sumatra to deliver on its promise.

Exerting pressure through the district government had not worked. In 2015, the company had signed a new, written commitment, brokered by local bureaucrats, to provide the plasma. But 16 months on, the tribe was still waiting.

Some of the villagers resolved to occupy the firm’s plantation. They built huts amid the oil palms, to hunker down in as a form of direct action. But the next day, news began to spread that London Sumatra had torn them down.

Anger mounted as the villagers gathered in Tebing Tinggi. “If this isn’t resolved today, we’ll burn down London Sumatra’s security post as a warning,” one man announced to the crowd, according to court records of his later conviction.

The villagers piled into pickup trucks and onto motorbikes for the ride to a security post inside the plantation. They pelted it with stones, before dousing it in gasoline and setting it on fire.

Then they moved onto the company’s office, smashing windows with stones and machetes. They piled in dried palm fronds and set them alight, and a crowd pelted the building with plastic bags filled with gasoline. Amateur footage captured the building full of smoke and flames.

The next day, as evening set in, police descended on Tebing Tinggi.

Lina, a Suku Anak Dalam woman then in her mid-30s, was at home with family when police broke down her door. She was taken to the police station along with more than 40 other members of the community.

“I was scared, thinking of what would happen to my child if I was imprisoned,” she told us.

By 2017, local media outlets across Indonesia were publishing a steady drumbeat of articles featuring communities accusing companies of failing to deliver on their plasma obligations. But these were almost invariably portrayed as isolated incidents — of one community locked into a dispute with one company.

To discern the bigger picture, we set out to compile Indonesian news articles about every plasma-related dispute published over the past decade. To this we added allegations documented in academic papers, reports by campaign groups, notices on government websites, and other online sources.

The resulting database revealed that allegations had been levelled against 155 oil palm plantation companies for failing to provide plasma over this period. These typically represented allegations made at some previous point in time, rather than disputes that were necessarily current. But their sum total indicated that far from being isolated incidents, the failure to provide plasma was a systemic problem potentially affecting hundreds of villages and thousands of people across the archipelago.

Substantiating the allegations that underpinned all of these complaints was beyond the scope of our investigation. But by analysing 52 cases in greater depth using publicly-available information, and interviewing affected villagers, two clear phenomena emerged.

First, companies were committing to provide plasma — whether legally required to or not — and then, according to communities, reneging on those promises for years, or even decades. Second, companies that acquired licences after 2007 were failing in their legal obligations to develop plasma.

Behind the groundswell of cases lay a multitude of human stories, of villagers who had been sold a dream only to lose their land and livelihoods for little or nothing in return.

“At first, their promise was very sweet,” a villager named Yustenli Duli told us in an interview in his village in the district of Bulungan, on the island of Borneo, site of a mass protest in 2017. “Our children will be able to go to school overseas … The people were lulled by sweet dreams that their future would not be difficult.”

Twelve years after the promise was made, he said, they were still waiting for the plasma.

The escalation of the communities’ actions reflected a growing desperation as cases dragged out without resolution: blocking roads and factories, seizing company vehicles, occupying plantations. Protests grew larger, to the point that hundreds or even thousands of people marched on government offices.

The decision to take direct action came with legal risks. In West Kalimantan, on the island of Borneo, Herkulanus Roby, a farmer in his early 30s, helped lead hundreds of farmers to the offices of a palm oil firm and chained its doors shut.

The farmers had given up their land but waited in vain for five years for any profits, our interviews with community members and extensive court records show. They vowed to keep the doors shut until the issue was resolved. Instead, they were arrested, and Roby and another farmer were jailed for 10 months. A third person, identified by prosecutors as the leader of the protest, was sentenced to four years.

“Of course, because it was wrong in the eyes of the law, I regret it,” Roby told us. “But on the other hand, our rights were taken away from us.”

In 2021, academics from Indonesia and the Netherlands published a study examining 150 land conflicts between communities and oil palm firms across four Indonesian provinces. They found that grievances over plasma underpinned 57 per cent of these disputes. It was the second-most prominent cause, after companies allegedly seizing community lands without their consent.

Ward Berenschot, a senior researcher at the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, who co-led the study, said his team identified cases where the Mobile Brigade Corps, a paramilitary police unit known as Brimob, descended on protesters.

“Most of the violence that we found is not carried out by the community, but by the police and the security personnel of the palm oil companies,” Berenschot said. “We saw quite a lot of injuries and a lot of violence.”

Villagers found the state could be swift and decisive when it came to cracking down on protests, if not on the underlying cause. The study found protest leaders were “frequently criminalised” and community members had been arrested in 42 per cent of the cases they examined. In total, 789 people were arrested.

In Tebing Tinggi, after dozens of Suku Anak Dalam were rounded up, armed police made them crouch down in a line and duck-walk single file into the subdistrict police station. There, villagers told us, they were physically assaulted by the police. One man, Johan, said he was hit so hard over the head with a bamboo stick that it broke.

“Without being questioned, we were beaten bloody,” he said.

Most of the Suku Anak Dalam were released without charge. Seven were prosecuted on charges of vandalism and jailed for 18 months.

Part 4: ‘The system is failing’

Within weeks of the conviction of the Suku Anak Dalam, in 2017, national politicians arrived in the tribe’s home district of North Musi Rawas.

Daniel Johan, a member of the national parliament, had learned of the land conflict through social media. He was then deputy chair of the parliamentary commission overseeing the palm oil industry, and brought the members to Sumatra to meet with the Suku Anak Dalam.

“If parliament has to choose, it will choose the community over the company,” Edhy Prabowo, the then head of the commission, told reporters during the visit.

The parliamentarians called the Suku Anak Dalam and London Sumatra to a hearing in October, in the commission’s wood-panelled meeting room in the parliament building in Jakarta. Daniel pressed company officials over the legitimacy of their claims to the Suku Anak Dalam land. “The community needs [the land] far more than you do,” he told them.

The officials demurred and ducked his questions. Daniel urged them to return the land to the tribe “as soon as possible” and gave them one month to do so.

With influential legislators now backing their cause, the tribe may have had reason to believe their wait was coming to an end. The next year, the district head signed two decrees identifying land that London Sumatra could use to give them 1,000 hectares of plasma.

Four years on, they’re still waiting.

“We were firm, we were tough,” Daniel Johan told us in a recent interview. “But the matter still hasn’t been settled.”

The Suku Anak Dalam case exemplified the government’s approach to solving such conflicts, which tends towards informal mediation between companies and communities, our investigation found. By the time of the Jakarta hearings, the tribe had attended a string of meetings brokered by government officials without securing a decisive intervention.

In a recent interview, Innayatullah, the deputy head of North Musi Rawas district, said his administration was still trying to solve it by finding consensus. “We’re grateful that London Sumatra has invested in our area,” he told us. “On the other hand, the Suku Anak Dalam also have rights. So we have this middle ground.”

We estimated that London Sumatra could generate $1.2 million a year from the 1,400 hectares of oil palm that the Suku Anak Dalam say is owed to them. In the two decades the case has dragged out, profits have likely surpassed $30 million. London Sumatra declined to be interviewed for this article. London Sumatra and Indofood Agri, its parent company, did not respond to a request for comment on an extensive list of findings from this investigation.

The academic study of 150 palm oil-linked conflicts found that “informal mediation and negotiation” was the most common intervention officials deployed in their attempts to resolve disputes. It also found that this frequently failed. Only 14 per cent of the mediations resulted in an agreement that was subsequently implemented.

“Demonstrations, mediation with local government, the provincial government, sending letters to the president … the case will rise up in the media, and then the government gives attention to the case, but after that it's lost,” said Djayu Sukma Ifantara, an activist with the Foundation for Sustainable Forest Communities who works with villagers across the Indonesian portion of Borneo.

Our media scan turned up 15 instances in which government officials threatened punitive action against companies over plasma disputes. A provincial legislator in North Sumatra called for the revocation of permits belonging to 19 companies if they failed to provide smallholdings; a national lawmaker said London Sumatra should lose its licence in another South Sumatra concession, not far from Tebing Tinggi; an official in North Kalimantan province warned he would take “strict action” against nine companies if they did not “immediately” provide plasma.

In an effort to find out whether authorities had made use of these powers, we interviewed officials at 14 plantation agencies from seven provinces, targeting jurisdictions where our media scan or reporting found widespread problems with plasma, or where officials had taken a public stance on the issue.

Some officials said their administrations had made decisive interventions. In one district on the island of Sulawesi, the district head had suspended a company’s licence after a dispute with villagers over plasma. In Ketapang, West Kalimantan, the head of the plantation office said he had convinced a company to increase its plasma from 18 to 20 per cent after issuing a formal written warning.

But these were the exceptions. In other jurisdictions where they recognised there was a problem officials tended towards a softer approach, involving mediation and “encouraging” companies to comply with their legal obligations. There was a general consensus that revoking permits was too harsh a measure.

“We have to be more persuasive first,” said Ujang Rachmad, head of the plantation agency in East Kalimantan province. “Closing down a company can have enormous social impacts. We have to consider all that.”

This approach was prevalent even in jurisdictions where there was evidence of widespread problems. In Rokan Hulu district in the Sumatran province of Riau, Samsul Kamar, an official in the district’s plantation agency, said he was dealing with disputes over plasma almost every week, with only “around 15 per cent” of the 77 companies under his jurisdiction providing enough, in his account. But they mediated and encouraged companies to comply, and the most stringent measure they had taken was issuing written warnings.

Daniel Johan, the national legislator who sought to intervene in Tebing Tinggi, said plasma disputes were allowed to persist because government authorities at the regional and central levels were not firm enough in enforcing the rules.

“The people are still screaming, their lives are becoming more and more difficult,” he told us. “They’ve lived in these places since the times of their ancestors, and now they’re being shunted aside. It’s happening everywhere. All the resistance they’ve mounted, sometimes even sacrificing their lives, and still there is no resolution. It means the system is failing.”

Djayu, the activist from West Kalimantan, pointed to a potential cause of the government’s reluctance to act.

Indonesian districts are governed by elected heads, known as bupatis, who would take ultimate responsibility for any decision to sanction a company over licensing violations. Research by academics and Indonesia’s anti-corruption agency suggest that it is common for companies or businesspeople to provide financing to candidates running for political office, in the expectation of favours from the winning ticket.

“Bupatis are elected by the community to put pressure on companies. But those same companies give money to support bupatis,” Djayu said. “That's the reality.”

Corruption can also take cruder forms.

In 2018, an employee of Golden Agri-Resources was arrested after handing over a black tote bag holding the rupiah equivalent of around $17,000 in cash to two provincial legislators in a Jakarta food court.

The politicians were members of a parliamentary commission that had visited one of Golden Agri’s plantations in the district of Seruyan in Central Kalimantan province, then announced to the media that it had polluted a lake, operated without all the permits it needed — and failed to provide plasma. The intent of the bribe, arranged by senior executives at the firm, was to mothball an impending inquiry in Central Kalimantan that would delve into the alleged offences.

The politicians were eventually sentenced to five years in prison. The executives were jailed for 20 months.

Golden Agri said the executives had gone rogue and taken their own initiative to pay the bribe. Their eventual conviction, the company wrote in a statement, “draws a line under this unfortunate and regrettable incident.”

Part 5: Oversight

The cases we identified in media reports and our own reporting are just the visible edge of what is likely a much larger problem, the precise contours of which appear to be unknown even to the Indonesian government.

A 2019 report by Indonesia’s Supreme Audit Agency, known as the BPK, arrived at a string of scathing conclusions about the government’s oversight of plasma. It found that the Ministry of Environment and Forestry and the Ministry of Agriculture had failed to properly monitor whether companies were complying with their legal obligations.

Oversight had been left to regional authorities, but the BPK warned their approach, which relied primarily on self-reporting by companies rather than any active monitoring, left open the possibility of “widespread illegal management” of plantations.

Government data was inconsistent, the audit found. The number of companies, size of plantations and scale of plasma differed from one agency to the next, from districts to the central government. “Disorganised” data collection led the BPK to conclude that companies’ compliance with plasma obligations “could not be monitored and evaluated.”

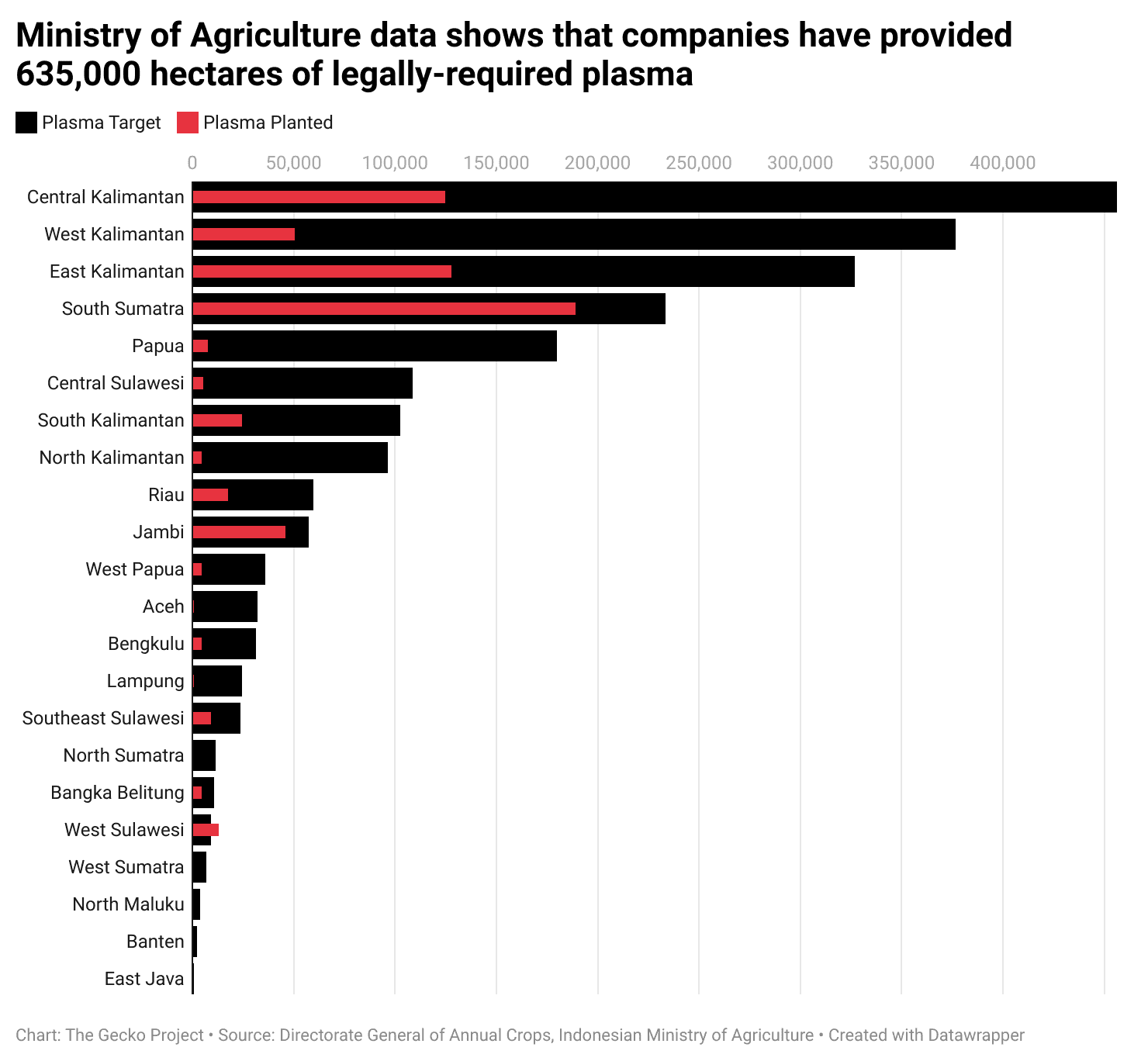

We set out to find out what the available data could tell us about the extent of companies’ failure to provide plasma. Earlier this year, the Ministry of Agriculture shared with us its latest tally of how much plasma had been developed by plantation firms.

The data showed that companies with licences issued after 2007, the year the 20 per cent requirement was enshrined in law, had shared some 635,000 hectares of their plantations with communities. But because it did not show how much land these companies had planted in total, it could not reveal on its own whether they were collectively providing plasma equivalent to 20 per cent of their estates or falling short of the legal target.

To bridge the gap, we turned to the ministry’s official publications, which showed that from 2007 to 2021, private companies had planted five million hectares of oil palm. If one-fifth of that should have been plasma, it would mean there was a shortfall of approximately 375,000 hectares, an area three times the size of Los Angeles.

Based on conservative estimates of profits from oil palm, we calculated that such an area of plantations was capable of generating profits of more than $330 million per year — money that should have been flowing to local communities but that was instead accumulating in corporate coffers. As plantations have a productive life of 25 years, on the basis of these figures, companies could eventually deprive villagers of around $8 billion.

Observed from one angle, this overcounted the shortfall, because some portion of that five million hectares would undoubtedly have been planted by companies with pre-2007 permits, which were not necessarily required by law to set aside a fifth of their estate for plasma. But other factors suggested it could underestimate the shortfall.

The data did not break down plasma provision by individual plantation, for example, so companies providing more than 20 per cent plasma could mask those falling short or with none at all. A study published this year also found that by 2019, the Ministry of Agriculture had undercounted the area of industrial-scale oil palm plantations by around 1.8 million hectares. If accurate, this could substantially increase the plasma shortfall.

Perhaps most tellingly, more robust evidence indicates that in just one province companies have failed to provide more than 100,000 hectares of plasma required by law.

We obtained government data for Central Kalimantan province that provides a detailed breakdown of how much each company has planted for its own estate and as plasma. The data also included permit dates, enabling us to separate out companies licensed before and after 2007.

This revealed companies withholding 103,000 hectares from communities. Our analysis suggests communities in this province alone, which is home to 20 per cent of the nation’s corporate oil palm plantations, could be losing more than $90 million every year.

The picture presented by this provincial data was reflected in statements from public officials. We found 22 news articles published in the past five years in which politicians and bureaucrats denounced companies in Central Kalimantan for failing to provide plasma. In 2019, Sugianto Sabran, the provincial governor, announced that almost 85 per cent of plantations there had not met their obligations, a situation he described as “outrageous.”

Activists had been urging President Joko Widodo’s administration to establish a clear picture of the problem since at least 2018. That year, 236 people from across Indonesian civil society put their names to an open letter to Jokowi, as the president is known, and the president of the Council of the European Union stating that plasma had been used to “take over” community lands. They urged the government to carry out a national audit of the programme.

Four months later, it seemed the request had fallen on sympathetic ears, as Jokowi issued a presidential instruction mandating five ministers and local authorities to audit every oil palm plantation licence in the country. The Ministry of Agriculture was tasked with evaluating whether companies were complying with plasma regulations, and three other ministries were instructed to verify data, find land for plasma, and speed up granting land rights to plasma farmers.

But it remains unclear if the review led to any action on plasma.

In early 2021, a report published by another government regulator, the Indonesia Competition Commission, known as the KPPU, concluded that communities had been exploited because of the failure to protect their rights through regulations governing plasma. It noted that Jokowi’s review was supposed to address this, “but there has still been no further information from the related ministries about the implementation of the Presidential Instruction, especially regarding plasma.”

This January, President Jokowi announced that his administration was revoking more than 100 permits held by plantation firms. Officials have referred to the companies being inactive or committing unspecified violations, but the basis of their decision has not been made fully clear.

Heru Tri Widarto, the secretary of the Directorate General of Plantations at the Ministry of Agriculture, declined to be interviewed for this article. But in response to written questions, when asked what the government had done to improve the situation, he pointed to new regulations governing plasma passed in 2021.

These new rules were implemented as part of a broad sweep of deregulation intended to make Indonesia more appealing to investors. They provide companies developing new plantations with a broader range of opportunities to create economic opportunities for communities, instead of plasma.

Meanwhile, one of the three ministries tasked with “accelerating” plasma provision suggested it had made little progress on that front. Surya Tjandra, deputy minister at the Ministry of Agrarian Affairs and Spatial Planning, told us the ministry’s understanding of the problem remained vague.

Four years on from the review being announced, he told us they had formed a task force on agrarian reform that is gathering data on plasma. “We are still collecting comprehensive information,” he said in an interview. “There really isn’t much.”

Part 6: The producers

To the outside world, the companies that dominate the palm oil industry present an image that suggests they are doing a good job on plasma. In their annual reports, many of them post buoyant figures showing that 20 per cent or more of their plantations are directly benefiting communities.

Determining how this squares with the profusion of allegations levelled against the same firms is challenging. The conglomerates operate as holding companies, often with two dozen or more subsidiaries, each with its own plantation, licences, and deals with communities. Depending on when those licences were issued, they may be subject to different legal requirements.

The conglomerates publish aggregate figures that make it impossible to verify, on that basis alone, which subsidiaries are compliant with the law. We asked 18 of the largest palm oil producers operating in Indonesia for a breakdown of their plasma and licences for each subsidiary.

Two companies, IOI Corporation and POSCO Group, shared data indicating they were compliant with the law. All of the others declined, saying it was confidential, “sensitive” information, required the consent of plasma scheme members, or did not provide a reason.

Two conglomerates pointed to audits of their operations carried out for the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil, or RSPO, an industry certification scheme. But these sources do not provide sufficient detail to establish a precise picture in many subsidiaries.

RSPO audits, we found, can also betray a blind spot for issues related to plasma. A 2017 audit of London Sumatra’s mill supplied by the plantation in Tebing Tinggi, for example, took place six months after the Suku Anak Dalam had burned down the company’s office. But it made no reference to the dispute and found “no negative issues” related to communities. The same week the auditors visited the site, seven members of the tribe were jailed for their role in burning the office.

To find out whether the public reports or the industry itself were presenting a more accurate picture, we set out to find out what was happening across the landbank of one conglomerate.

Golden Agri-Resources, controlled by the billionaire Widjaya family, controls more than half a million hectares across Indonesia. Overall, the company reports that almost 21 per cent of its total planted area is plasma. But digging into audits of its plantations, government data, public reports and interviewing villagers paints a more nuanced picture.

That headline figure, we found, appears to be skewed by a small number of plantations providing a disproportionately large amount of plasma. Just five of its 54 subsidiaries represent 36 per cent of the total. These are older concessions dating back to the 1990s and early 2000s, on the island of Sumatra, when it was not uncommon for companies to provide around 70 per cent of their plantation as plasma.

The large areas in Sumatra masked a very different situation in multiple other subsidiaries. In eight, Golden Agri has acknowledged publicly or in response to our questions that it is required by law to provide 20 per cent plasma but has not yet done so.

In response to a detailed list of questions, Wulan Suling, Golden Agri’s head of corporate communications, acknowledged in an email that the company had not provided 20 per cent in all plantations where it was required to do so, and wrote that this remains “a work in progress”.

In a subsequent interview, Susanto Yang, who runs the company's operations in West Kalimantan, said a key cause of delays was the complexity of working out which farmers in a given area were eligible for plasma, and how to divide it among them. He also said once they had done so, it was challenging to determine where to place the plasma.

“It takes time, it takes patience, it takes everyone's support,” he said. Susanto estimated it should take two or three years to get the process right.

A Golden Agri subsidiary called Bumi Sawit Permai, operating in South Sumatra, was required to develop 1,500 hectares of plasma as a condition of a permit it acquired in 1998. Twenty years on, RSPO audits showed it had established more than 5,000 hectares of oil palm, but given nothing to communities.

A law firm commissioned by the RSPO concluded in 2016 that the subsidiary was legally obligated to provide plasma, despite its claims to the contrary. In February, Golden Agri told us it had developed 700 hectares — less than half the area required by its licence — while the development of the rest was “still underway.”

In West Kalimantan’s Kapuas Hulu district, a region towards the centre of Borneo, Golden Agri signed up farmers to a plasma scheme in 2007. The company planted its own land, but failed to plant all of the plasma it had promised for several years.

In 2014, two NGOs submitted a complaint about the case to the RSPO, which operates a grievance procedure intended to hold members to their voluntary commitments. Six months later, the RSPO ruled that Golden Agri had failed to provide all the plasma it had promised and restricted it from developing any new land until it felt the complaint had been addressed.

Golden Agri later told the RSPO that by 2018, it had provided just over 1,000 hectares of plasma in the Kapuas Hulu concession. This was more than a decade after it had first approached the communities. Marcus Colchester, of the Forest Peoples Programme, noted that the delays in planting meant that “some of the individuals who surrendered lands in 2007 aren't going to really see a significant return for almost a generation.”

In February this year, a local politician on the island of Borneo temporarily shut down a Golden Agri subsidiary he said had failed to provide plasma, after operating for 13 years. Jaya Samaya Monong, the head of Gunung Mas district, said communities had staged protests to demand plasma in 2012 and 2014, without any result.

He made a campaign pledge to hold the firm to account when he was running for office in 2019. Despite meeting company officials twice, Jaya said his efforts had failed too.

Jaya stationed police to stop company trucks leaving the plantation in what was a rare occurrence of a government official taking decisive action in a plasma case. “Maybe if there’s no firm action that could harm them, they think they can ignore it,” he told us in an interview.

Golden Agri stated that the company had started work to establish plasma in this subsidiary in 2015 and hoped to begin planting the community’s portion of the plantation in 2023.

In Golden Agri’s broader explanations, another challenge the company said it faced was a shortage of land. In response to our written questions, four other conglomerates also cited this as an obstacle to establishing plasma.

One of the reasons this arises is where companies attempt to establish plasma schemes where all of the viable land has already been used up by plantation firms, according to Tania Li, an anthropology professor at the University of Toronto.

“The corporation says, ‘Oh, well, we can't do the 20 per cent because there's no more land left,’” said Li, who has done extensive research on Indonesia’s palm oil sector. “Well, that's because they have it all. They have a series of plantations, kind of back-to-back saturation.”

A second reason it occurs is because some companies have adopted policies prohibiting them from cutting down rainforest or expanding into peatlands, practices that destroy animal habitats and release greenhouse gases. Pressure from buyers has forced most palm oil producers to set aside such areas within their land banks. In some cases, the areas they have set aside were slated for plasma.

For some, there is an obvious solution: companies could simply provide the plasma from within the areas they have been able to develop. Jaya, the district head from Gunung Mas, said he had told Golden Agri to do just this.

“I don’t want to hear any more excuses,” he said. “Because it’s simple: plasma is supposed to be built in tandem with the main plantation. Why is there a main plantation but no plasma plantation?”

When Golden Agri told the RSPO it could not find enough land for plasma in Kapuas Hulu, the Forest Peoples Programme also made repeated suggestions it could provide it from its own estate. Golden Agri declined, on the grounds that its bank loans and permits made it “virtually impossible” to do so.

There could be another reason for companies to avoid this option: it would cost them.

In a 2018 memo to Singapore’s stock exchange, the plantation conglomerate Sawit Sumbermas Sarana acknowledged that it was not compliant with Indonesian plasma regulations and might have to hand over some of its own plantation to communities. Doing so, the firm wrote, “could have a material adverse effect on our business, financial condition, results of operations and prospects.”

Part 7: The buyers

The consumer goods firms that hoover up thousands of tonnes of palm oil each year and shuffle it onto supermarket shelves have promised to root out “exploitation” of people from their supply chains.

These commitments have been driven by years of pressure by activists and journalists presenting evidence of oil palm plantation firms annexing community lands and committing labour rights abuses. But when it comes to plasma, the palm oil buyers appear to have a blind spot.

We compared the most recent disclosures published by these consumer goods firms on their Indonesian suppliers with our database of public allegations linked to plasma. This indicates that more than a dozen major consumer goods firms have sourced palm oil from producers alleged to have withheld plasma, or the profits from plasma, from communities over the past eight years.

They were also connected to cases that were the focus of our investigation. Johnson & Johnson and Kellogg’s, for example, buy palm oil from the company that owns the plantation in Tebing Tinggi. The make-up manufacturer Avon bought from the mill that processes fruit produced on Suku Anak Dalam land.

In response to our findings Avon stated that it “will take action to investigate further”.

Johnson & Johnson wrote that they “take these allegations very seriously” and had initiated their grievance process. Kellogg’s said the company would investigate the allegations and “coordinate with our suppliers to determine next steps”.

Meanwhile, a dozen firms — including PepsiCo, Unilever and Nestlé — report that they are sourcing from the Golden Agri plantation that was shut down by a local politician in March 2022, after failing to provide plasma for more than a decade.

We presented a summary of our findings to these palm oil buyers, highlighting their supply chain connections to specific cases we had examined in depth, and to a larger number of cases in our database.

In response, the buyers pointed to their existing policies aimed at protecting human rights and eliminating "exploitation" from their supply chains. Some noted that they required their suppliers to comply with the law. They said they engage with their suppliers when potential violations of these policies are brought to their attention, and would do so for the cases identified in our article.

Some of the buyers acknowledged that the problems went beyond the individual cases our investigation identified. Reckitt wrote that the findings “suggest potential systemic problems” that “require further investigation and coordinated action by various public and private stakeholders to address”.

Four companies committed to broader efforts to determine and mitigate their exposure to problems with plasma. Colgate-Palmolive, for example, stated that “the failure of compliance with plasma commitments represents a wider systemic issue”. It stated that the company would develop a due diligence process to check its suppliers were providing sufficient plasma, and monitor whether they were able to “identify and address community conflicts linked to unfulfilled plasma obligations.”

Djayu Sukma Ifantara, the activist from West Kalimantan, said palm oil buyers offered communities an important means of pressuring plantation firms where the government had failed to act. “For now, it’s the best way,” he said. “The buyers have to open their eyes, open their mind about these conflicts, and find the right solution.”

However, Djayu noted the limitations of these methods. Pushing disputes through international buyers takes a lot of time, he said, and could not solve the most fundamental problems. If communities wanted their land back, for example, it would require government intervention.

“The solution has to come from the government,” he said. “It’s their responsibility, their obligation, mandated by the law of Indonesia.”

In a plantation in North Musi Rawas, one day last year, Siti Maninah’s hands reached through the weeds to feel for the bright orange fruitlets that lay on the ground.

On a good day, Siti, one of the elders of the Suku Anak Dalam, will gather up 10 kilograms to sell to the mill. That will be enough for her to feed her family for the day.

Most days they get enough, but other days they go without. She worries what will become of the tribe’s children when they grow older, with their ancestral land controlled by London Sumatra.

“We can’t stand this life anymore,” she said. “We want our land returned to us as soon as possible.”

Reporting team

The Gecko Project

Margareth Aritonang, Tom Johnson, Safrin La Batu, Ian Morse, Gilang Parahita, Rio Tuasikal, Tom Walker.

Mongabay

Ari Anggara, Jaka Hendra Baittri, Elviza Diana, Philip Jacobson, Yusie Marie, Aseanty Pahlevi, Yitno Suprapto, Suryadi, Taufik Wijaya.

Independent

Eko Nurcahyono, Boris Pasaribu, Fatahur Rahman, Petrus Suwito, Masrani Tran.

BBC

Aghnia Adzkia, Astudestra Ajengrastri, Rebecca Henschke, Muhammad Irham, Haryo Wirawan.