-

This is the first installment of Indonesia for Sale, an in-depth series on the corruption behind Indonesia’s deforestation and land rights crisis.

-

Indonesia for Sale is a collaboration between Mongabay and The Gecko Project.

-

The series is the product of nine months’ reporting across the Southeast Asian country, interviewing fixers, middlemen, lawyers and companies involved in land deals, and those most affected by them.

Prologue: Jakarta, 2007

On Nov. 29, 2007, on the tenth floor of a marble-clad office block in Jakarta, the scion of one of Indonesia’s wealthiest families met with a visitor from the island of Borneo.

Arif Rachmat, in his early 30s, was heir to a business empire and an immense fortune that would place him among the richest people in the world. His father had risen as a captain of industry under the 32-year dictatorship of President Suharto. After a regional financial crisis in 1998 forced the dictator to step down, Arif’s father had founded a sprawling conglomerate, the Triputra Group, with businesses ranging from mining to manufacturing.

Arif had come of age as one of the most privileged members of the post-Suharto generation, attending an Ivy League university and cutting his teeth in a U.S. blue-chip company. He had recently returned home to join the family firm, taking charge of Triputra’s agribusiness arm. Now he meant to position it as a dominant player in Indonesia’s booming palm oil industry.

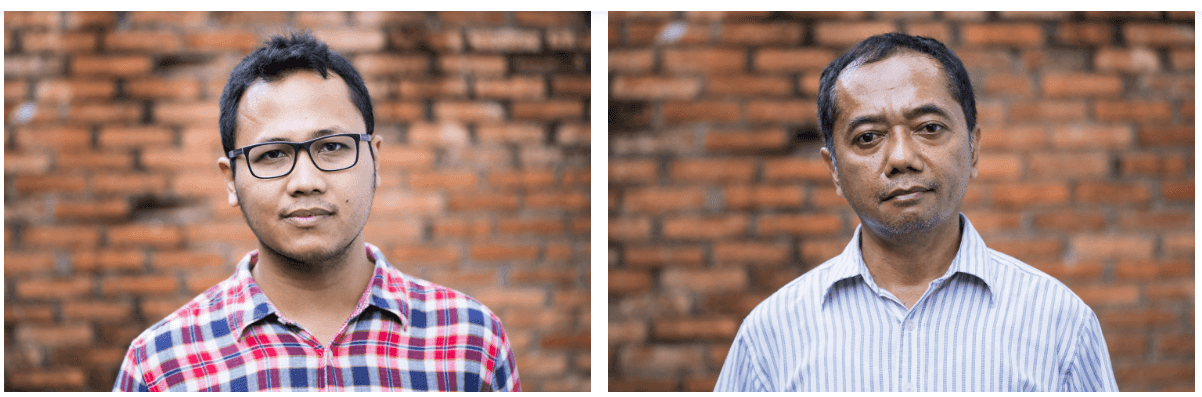

Arif’s visitor that Thursday was Ahmad Ruswandi, a chubby young man with glasses and a propensity to break out into a nervous smile and giggle. A contemporary of his host at the age of 30, Ruswandi came from a different place, but could have been forgiven for thinking his fortunes were on the rise as he rode the elevator up the Kadin Tower.

Ruswandi’s father, Darwan Ali, was chief of a district in Indonesian Borneo named Seruyan, putting him at the vanguard of a new dawn of democracy in Indonesia. Darwan was among the first of the politicians chosen locally to run districts across the nation, after three decades in which Suharto had held the entire country in a tight grip. These politicians, known as bupatis, were afforded vast new powers, including the ability to lease out almost all of the land within their jurisdictions to whomever they deemed fit to develop it.

The bupatis had a choice. They could attempt to usher in economic development while safeguarding the rights of the people they represented. Or they could repeat the sins of Suharto, who had plundered Indonesia’s resources in an orgy of crony capitalism.

The scene in the Kadin Tower would give some indication of the direction Darwan had taken. As the afternoon rush hour descended on the capital, his son Ruswandi sold Triputra a shell company with a single asset, a license to create an enormous oil palm estate in Seruyan. The license had been issued by Darwan himself, who was now in the midst of an expensive re-election campaign. It was not the first shell company Ruswandi had sold, and he was not the only member of the family who would cash in on Seruyan’s assets.

Over the past nine months, The Gecko Project and Mongabay have investigated the land deals that were done in Seruyan during its transition to democracy. We followed the trails of paper and money, tracked down the people involved and talked to those affected by Darwan’s actions. It was a journey that took us from law firms in Jakarta to a prison in Borneo, from backwater legislatures to villages that stand like islands amid a sea of oil palm.

These deals played a part in one of the greatest explosions of industrial agriculture the world has ever seen. In a few short years after Darwan and dozens of other bupatis assumed authority, plantations multiplied throughout the archipelago nation. The resulting destruction of Indonesia’s tropical rainforests catapulted it toward the top of the list of countries fuelling climate change.

This agricultural surge is routinely cast as an economic miracle, rapidly bringing income and modernity to undeveloped regions. In this narrative, expansion was planned, controlled and regulated. The harm to the environment was an unfortunate side effect of the moral imperative of development.

But there is another version of the story, one that played out through backroom deals and murky partnerships. In this story, unaccountable politicians carved up other people’s land and sold it to the children of billionaires. Farms that fed the rural poor were destroyed so that multinationals could produce food for export. Attempts to rein in the bupatis were undermined by their ability to buy elections with palm oil cash, and they came to be known, in a nod to Suharto, as “little kings.”

Darwan’s Seruyan deals, while vast, represent a fraction of the total. Their significance lies in what they tell us about how the system was gamed, to allow district chiefs to exploit natural resources, subvert democracy and turn the state into a force that acts against rural people. By delving into his story, we expose the inner workings of a system that can be seen in operation across the country.

Today, the actions of bupatis like Darwan reverberate throughout Indonesia, as conflict and deforestation continue in lands they ceded to companies. Understanding the corruption that occurred in this fragile period may hold the key to ending the crisis.

Part One: Indonesia reborn

Darwan’s son Ruswandi was a 21-year-old university student when thousands of protesters occupied the House of Representatives in 1998, demanding the resignation of the ageing Suharto. A regional financial crisis had sent the rupiah into freefall, depriving the dictator of his ability to paper over deep inequalities. Economic growth, as well as a willingness to use the army to impose violent control, had served as the bedrock of his regime. But as the economy collapsed, food supplies dissipated and rioters filled the streets nationwide, he was abandoned by his allies, and finally stood down.

For three decades Suharto had placed whole sectors of the economy in the hands of his relatives and cronies. He was formally charged with embezzling hundreds of millions of dollars in state funds via a network of charities, although he successfully claimed to be too ill to stand trial. A Time magazine investigation estimated that the family had amassed a fortune of US$15 billion. Transparency International ranked him as the world’s most corrupt leader.

In the leadership vacuum that followed his resignation, the country threatened to break apart. An implausible nation-state composed of a multitude of ethnically and linguistically diverse people, living across thousands of islands, Indonesia had been held together by military-enforced, highly centralised rule. The bureaucracy had been dominated by Javanese, people from the densely populated island that provided the state with its de facto cultural identity. As their dominance was eroded, long-suppressed identities re-emerged as potent forces. Without the heavy centre of gravity Suharto had provided in Jakarta, the regions began to spin out of its orbit of control.

The jockeying to replace the authority of the Suharto regime catalysed sectarian violence across the archipelago. Separatist insurgencies gained steam in Aceh and Papua. Christians and Muslims slaughtered each other in the Maluku Islands. In Kalimantan, the Indonesian part of Borneo, the notion that indigenous Dayaks had been trodden upon was used to foment violence against migrants in the town of Sampit. Everywhere, the goal was control of resources.

The prize in view for those who could clamber their way to the top was a share in the spoils of Indonesia’s immense natural wealth. Its islands sat atop precious metals and fossil fuels, and were coated in tropical rainforests replete with valuable timber. For three decades, everyone had looked on, powerless, as the revenues from exploiting these resources flowed out of the islands, to Jakarta and the personal accounts of Suharto’s family and cronies. Now they were up for grabs.

It was in this turbulent environment that Darwan Ali emerged as a political force. Darwan had grown up in a staunchly Muslim village on the banks of Sembuluh, a sprawling lake at the heart of East Kotawaringin district, in Central Kalimantan, the largest province in Indonesian Borneo. His origins remain mysterious even to those who have studied the area, but an elder man from the same community told us he was born in the early 1950s into an ordinary family. His parents were tailors who also farmed a small plot of rubber, and named their other boys Dardi, Darlen, Darhod and Darwis. By the 1990s Darwan was operating in the district capital, Sampit, at a time when the local economy was overwhelmingly dependent on logging. Precious hardwoods were extracted from jungles that once cloaked the entire island. The timber was floated downstream into Sampit to be processed and exported.

The logging expanded far beyond what could legally or sustainably be harvested. A shadow economy flourished, predicated on hard cash flushing in from a timber trade unlicensed — but tacitly endorsed — by the local government. Darwan moved in this world, first as a building contractor for infrastructure projects, then as a lobbyist for industry, and finally as a prominent local member of the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle, or PDIP.

Darwan’s occasional appearances in local newspapers at the time chart his rise as a representative of the business community, pushing back against any efforts to regulate it or curb its worst excesses. He protests the banning of companies from bidding for government projects due to corruption; he earns controversy for gaining an untendered contract to supply schools with furniture; he complains about taxes imposed on the forestry sector, intended to prevent illegal logging. “The overall impression is of a typical Borneo frontier businessman who makes a lot of money in the black economy,” said Gerry van Klinken, a University of Amsterdam professor who follows Kalimantan politics closely.

“The overall impression is of a typical Borneo frontier businessman who makes a lot of money in the black economy”

As Jakarta’s hegemony receded, and the grip of Suharto’s circle on natural resources dissipated, the shadow economy and the characters who controlled it came to the fore. A timber mafia coursed into protected areas. Tanjung Puting National Park, a mostly swampy forest teeming with orangutans, leopards and crocodiles, was heavily targeted for its ramin and ironwood trees. One local government agency that attempted to stem the flow of logs had its office burned to the ground. When a journalist reported on the illegal logging of the park, he was soon after jumped upon, hacked with machetes and left for dead in a ditch. He narrowly survived, crippled and disfigured.

Beginning in 1999, Indonesia embarked on an ambitious programme of decentralisation, transferring a wide range of powers from Jakarta to local bureaucracies in the hope of both heading off separatist urges and making government more accountable. District heads, the bupatis, were granted the authority to enact their own regulations, provided they did not conflict with existing laws. They exercised this authority liberally. One of the first decisions of the East Kotawaringin administration was to begin taxing shipments of illegal logs, tacitly endorsing the shadow economy instead of confronting it.

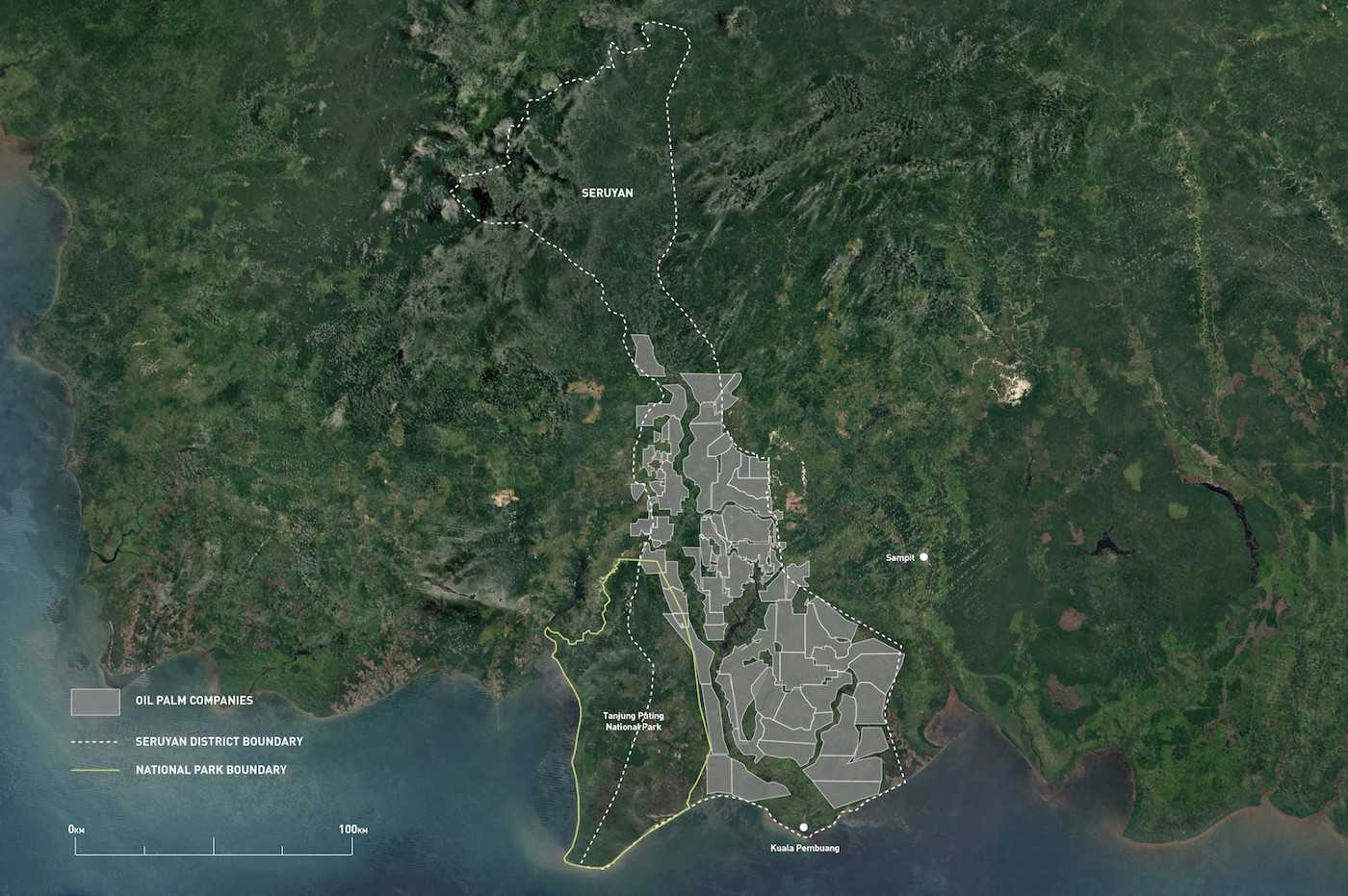

In 2002 Seruyan, named for the river that flowed through it, was carved out of East Kotawaringin as a new district. The following year Darwan, who was by then the head of the PDIP party in East Kotawaringin, became Seruyan’s first bupati. His jurisdiction stretched some 300 kilometres north from the Java Sea into remote jungles populated sparsely by indigenous Dayaks. Its western edge encompassed part of Tanjung Puting National Park. It was dominated by the lowlands between the park and Sampit, with Lake Sembuluh at its heart. At the turn of the millennium, more than two thirds of the district remained covered in forest. Though it was thinned out by logging, it harboured a wealth of wildlife that could rival most landscapes on earth.

The first generation of empowered bupatis were selected by members of the district parliament. Darwan’s ascent surprised some observers, who saw him as a political novice. He was said to have declared that any bureaucrat who backed his candidacy would rise in rank from echelon one to two, or echelon two to three, and so on, failing to grasp that this would actually constitute a demotion. But he was also viewed as a putra daerah, a “son of the soil”, who would fight for his people. He was awarded a five-year term, half a decade to transform the fortunes of his homeland, before facing his constituents at the ballot box.

By 2003 the district economy was stagnating. The log trade was collapsing under the burden of its own excesses. Lake Sembuluh had been a shipbuilding centre that attracted craftspeople from other islands at its height. But the vessels were made from hardwood and for transporting it, and the industry died as the commercial timber dried up. With the most valuable trees already stripped from the forest, Darwan was taking the reins of a district whose heyday as a timber hub, its main source of income, was coming to a close.

Darwan Ali was viewed as a putra daerah, a “son of the soil”, who would fight for his people

Plantations, specifically for oil palm, were the most obvious replacement. The fruit of the oil palm tree yielded an edible fat used in everything from chocolate to laundry detergent and biofuel. The commodity was in increasing demand globally, and the region south of Lake Sembuluh was seen as having great potential for large-scale development of the cash crop. Though it lacked infrastructure, it was close to the port towns of Pangkalanbun and Sampit. District officials imagined the latter as a vibrant transit town, for labourers coming in to work the plantations and palm oil leaving for global markets. Darwan announced plans to invite investors from Hong Kong and Malaysia. He promised a new harbour to facilitate exports and an easing of regulations.

Marianto Sumarto, a local sawmill owner who had joined Darwan’s campaign team in 2003, said the assumption of power by a son of the soil generated hope. “It made people proud,” he told us. “They didn’t know that behind the scenes, he was playing a bigger game.”

Part Two: The plantation boom

The handful of plantation companies present in Seruyan before Darwan arrived on the scene had stoked simmering resentment. Villagers claimed the first they knew their land fell inside a license issued to PT Agro Indomas, near Lake Sembuluh, was when their farms were torched or bulldozed. Owned by a pair of Sri Lankan billionaires, the company desecrated their graveyards, prompting villagers to destroy a bridge inside the concession.

A man whose land was taken by a company called PT Mustika Sembuluh later told an NGO that people had been offered no choice but to accept compensation on the company’s terms in what was viewed as a “forceful” land transfer. “If we resisted, we faced the security apparatus brought in to guard the company’s operations,” he said. “Our village chief told us back then that if anyone refused to give up the land the company would proceed to clear those lands anyway because they had the permit, and because our lands are state land anyway.”

The plantations polluted the lake and rivers to the point that drinking water in some areas had to be brought in by tanker truck. It also dried up the fishing trade, which along with the collapse of shipbuilding fuelled a “tremendous outmigration” of men, said Gregory Acciaioli, a University of Western Australia lecturer who did fieldwork in the district. “There were an enormous number of female head of households who were working, filling polybags with soil and seedlings for the oil palm plantations,” he told us. “They were barely scraping by.” He added, “It was a pretty depressed situation.”

Despite these experiences there was a new optimism about large plantations early on in Darwan’s reign, according to Mashudi Noorsalim, a researcher who has studied the growth of Seruyan’s oil palm industry. When Darwan took office, some were bullish about the prospect of employment, or of earning contracts to transport fruit or build access roads. Noorsalim told us that many residents thought things would improve because Darwan, the man shepherding in a new wave of investment, was a son of the soil. “Some of the people believed he would make the plantations help them,” he said.

As a bupati, Darwan could give licenses to whomever he wanted, without public consultation or bidding. The Ministry of Forestry theoretically exercised control over a late stage of the permitting process in areas of land that fell under its extensive jurisdiction. But across Central Kalimantan province the ministry was mostly ignored, removing the final check on the bupatis’ permitting powers. In Seruyan, this led to a boom in plantation licenses that exceeded almost every other district in Indonesia.

“Some of the people believed Darwan would make the plantations help them”

Our analysis of permits from government databases and other sources shows that between 1998 and 2003, only three licenses were awarded to oil palm companies in Seruyan. In 2004 and 2005, Darwan issued 37, collectively covering an area of almost half-a-million hectares, more than 80 times the size of Manhattan. This matched a similar pattern across Kalimantan, albeit on a larger scale, as bupatis took advantage of their control over land deals, handing out a flurry of licenses that led to an explosion in deforestation.

Among the first to get a license from Darwan was the BEST Group, a company privately owned by the Indonesian Tjajadi brothers. In a brazen disregard for the law, Darwan gave them a license that overlapped with Tanjung Puting. The national park had received a stay of execution in 2003, when Jakarta finally took action against the illegal logging ravaging its interior. Security forces descended on the park in a display of power intended to signal that the heyday of uncontrolled timber extraction was over.

The Ministry of Forestry pressed Darwan to revoke the permit. But in a signal of where the real power lay in this new dawn, he stood firm, and BEST ploughed its bulldozers into the protected forest.

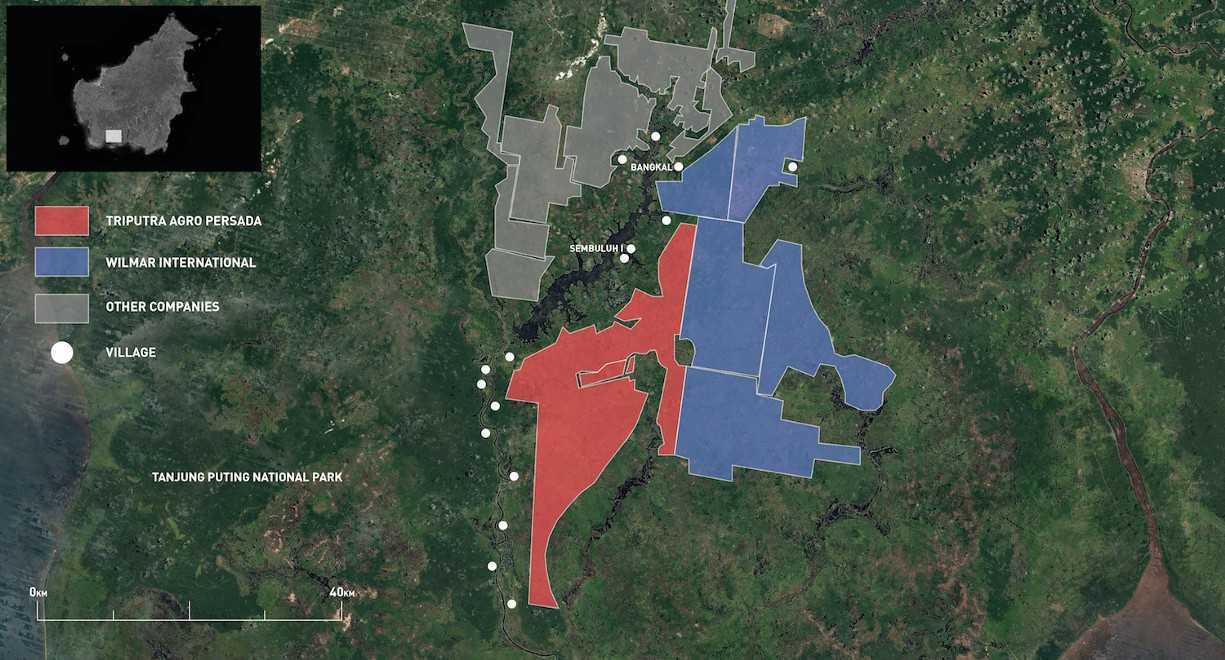

Among the early movers were some of Southeast Asia’s wealthiest families. By the time Darwan took office in 2003, Robert Kuok, then Malaysia’s second-richest man, had a credible claim to be the district’s largest landowner. His Seruyan plantation portfolio would later be merged with another company within the sprawling family business to form Wilmar International, possibly the largest palm oil firm in the world.

In 2005, Arif Rachmat became CEO of his family’s agribusiness arm, Triputra Agro Persada, and clearing began in one of its first ventures, a giant concession south of Lake Sembuluh. Two of Indonesia’s wealthiest families were brought together under the corporate structure that owned his firm’s plantations in Seruyan.

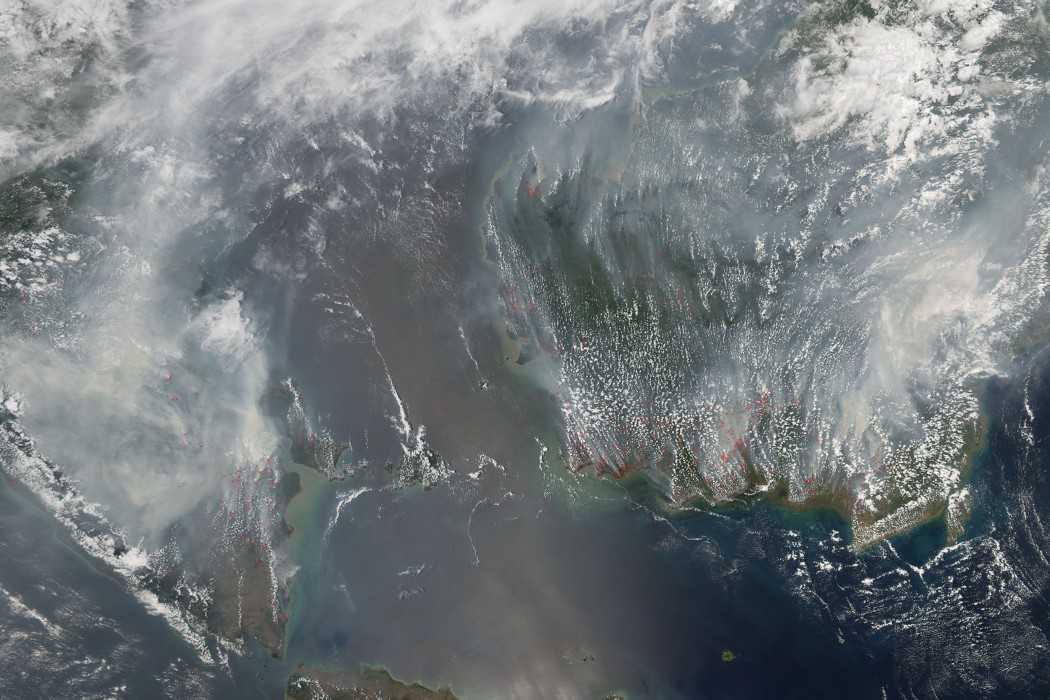

Borneo’s forests held immense volumes of carbon that were released when they were cleared for plantations. In the island’s southern stretches much of this jungle grew on peat bogs, composed of deep layers of organic matter built up over thousands of years. To plant on peat, oil palm growers dug vast trenches to drain it of water. This made it rapidly decompose, releasing powerful greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The dried peat was also highly flammable. Both companies and farmers had a habit of using fire to clear land for agriculture. In 2006, Indonesia experienced one of the worst burning seasons in memory, as smoke from fires across Sumatra and Kalimantan set off a carbon bomb and blanketed the region in haze visible from space. Under Darwan’s watch, Seruyan was among the worst-affected areas.

In a 2007 documentary on the impact of palm oil in Seruyan, a villager points to a few tall trees left standing in a denuded landscape. At the crest of one sits a huge orangutan. The primates relied on the expanse of forest that stretched across Seruyan’s southern reaches for their habitat. They could survive the loss of some of the largest trees to loggers, but not the outright flattening of their home for plantations.

The same year that Seruyan went up in flames, a report commissioned by the British government drew attention to the scale of emissions from global deforestation, which had become more significant even than the fossil-fuel guzzling transport sector. In 2007, the World Bank arrived at the startling conclusion that due to the destruction of its jungles and peatlands, Indonesia was producing more greenhouse gas emissions than any nation but the U.S. and China.

Deforestation and changes in land use — a euphemism for the advance of plantations — accounted for some 85 percent of Indonesia’s emissions. Globally, the country accounted for more than a third of emissions within this category, now recognised as a primary driver of climate change.

Due to the destruction of its jungles and peatlands, Indonesia was producing more greenhouse gas emissions than any nation but the U.S. and China

The majority of forest loss in the archipelago was occurring on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo, which bore the brunt of the plantation growth. But even there, the destruction was concentrated in just two provinces: Riau on the east coast of Sumatra, and Central Kalimantan, home to Darwan Ali. The region had become central to a global crisis, and Seruyan was playing its part.

Part Three: Whistleblowers

One day in early 2007, a car rolled up outside the home of Marianto Sumarto, the sawmill owner who had helped Darwan get elected. He lived in Kuala Pembuang, a small coastal town that serves as Seruyan’s capital. Marianto recognised the man behind the wheel as a government official, as he rolled down the window to hand over a bundle of papers.

“Take a look at these — there are some issues,” the man said flatly, before driving off.

When Marianto examined the dossier, he found copies of plantation permits Darwan had given to a handful of companies, with a list of directors and company addresses. He immediately recognised the names of some of Darwan’s relatives. Among the addresses, he noted the Kuala Pembuang home of Darwan’s brother.

“I don’t know why he brought me that data,” Marianto told us earlier this year, sitting outside the same house where he had met the whistleblower. “Maybe he cared about Seruyan and wanted to right the ship. Maybe he felt disappointed with how things were going and thought I’d be brave enough to do something about it.”

A migrant from the island of Java, Marianto had arrived in Kalimantan in 1985, joining a friend’s shipping company before switching over to a Malaysian-run timber outfit. He learned on the fly, eventually striking out on his own as an “illegal logger,” as he put it.

“Maybe he felt disappointed with how things were going and thought I’d be brave enough to do something about it”

When Seruyan formed, Marianto became head of the PDIP party within the new district, at the same time that Darwan was leading the party in neighbouring East Kotawaringin. He joined his campaign to become bupati, in 2003, and his brother-in-law became Darwan’s first deputy. But by the time he met the whistleblower, Marianto had soured on Darwan’s rule. He felt he had betrayed the hope that Seruyan would be developed for the benefit of its people. The plantations he had allowed to flood in were having the opposite effect. “That’s what I saw,” Marianto told us. “Maybe I’m the most critical person in this district.”

Wiry and tall, Marianto had a bald head, a raspy voice and a grin that curled upward. When we met, two of his fingers were wrapped in gauze; he had damaged them in a car accident a few days earlier and lost both fingernails. His nickname, Codot — meaning “bat” — was a relic from his days in an amateur rock band in the 1980s. “I know just about everyone in Seruyan,” he declared. “And everyone in Seruyan knows of me.”

A few days after the leak, Marianto and a friend made the four-hour drive to Sampit, to check out a collection of other addresses in the documents. He recognised the first as the home of Darwan’s son, Ahmad Ruswandi. They had held campaign meetings there in the run-up to his selection as bupati. Once or twice Marianto had stayed the night. He knew the next one too. It belonged to Darwan’s tailor, who had made their PDIP party shirts.

“The thing is, our country is a corrupt country,” Marianto told us. “A lot of public officials, they didn’t want to bring Seruyan to life. They just wanted to suck it dry.”

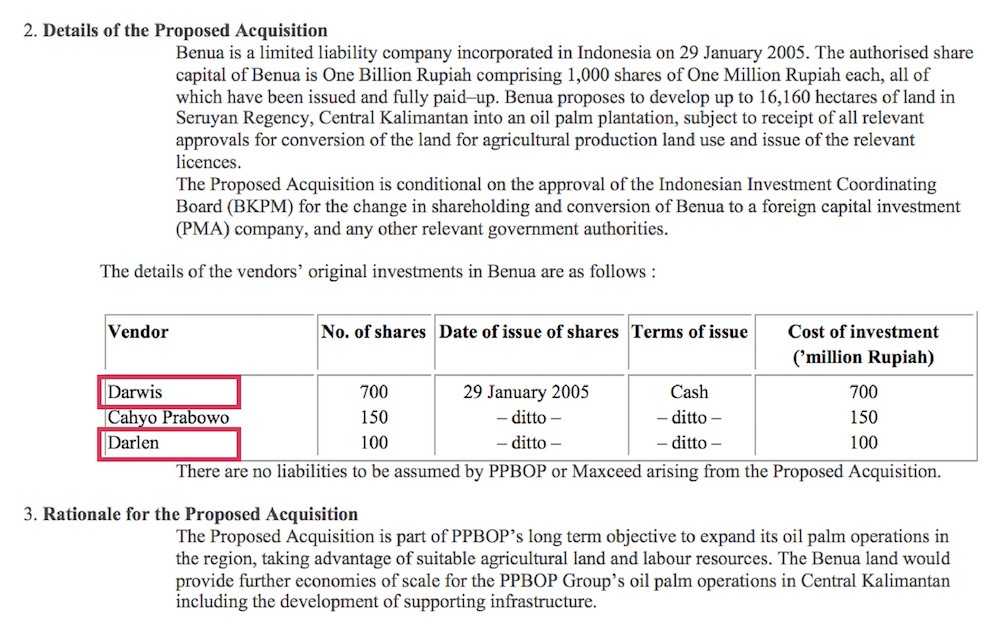

The Gecko Project and Mongabay pieced together the story behind Darwan’s licensing spree based on stock exchange filings, government permit databases and company deeds. More information and testimony were provided by Marianto, and a local activist named Nordin Abah, who separately investigated Darwan around the same time as Marianto. We corroborated our findings in interviews with people involved in several of the companies.

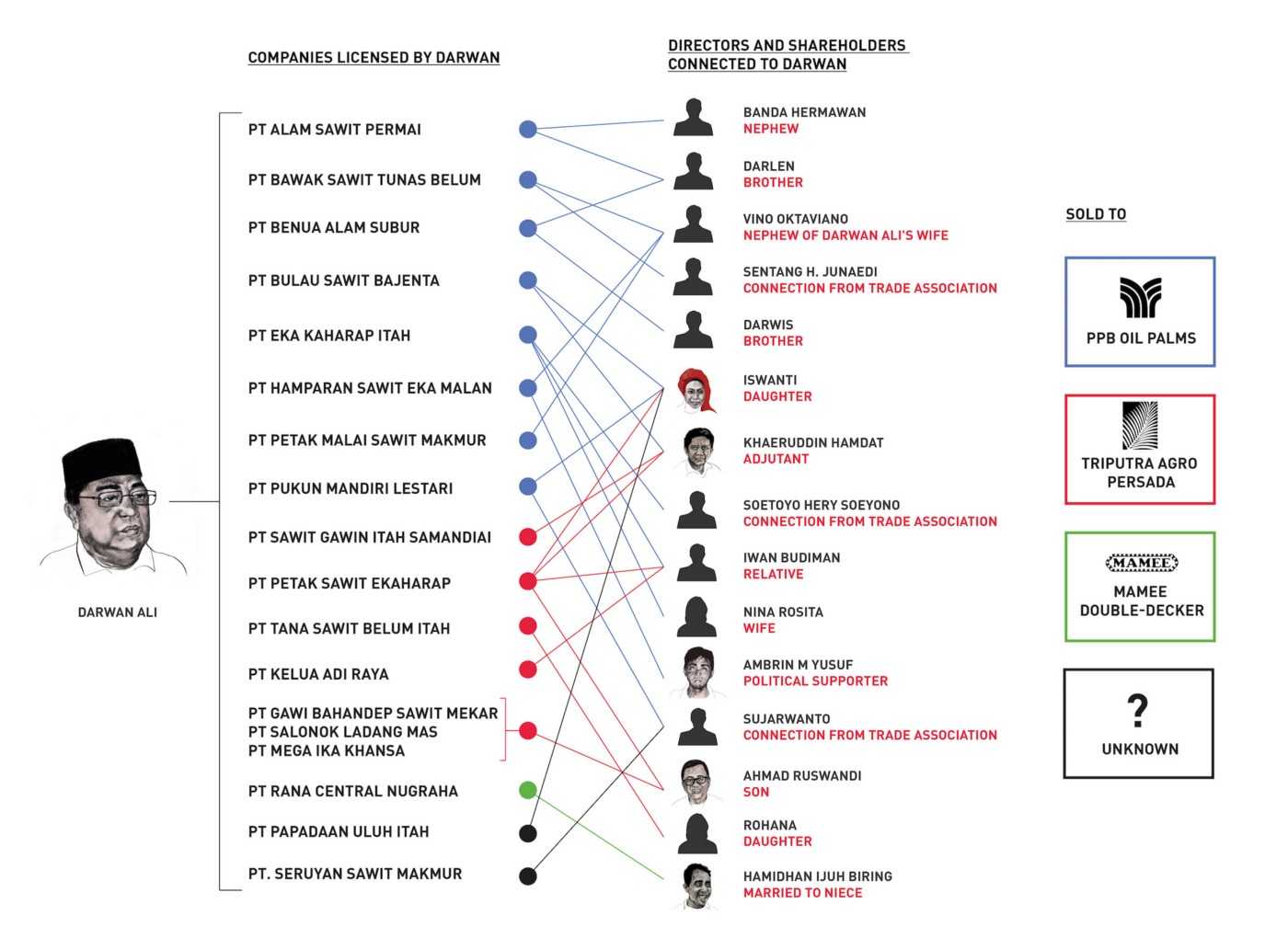

The picture that emerges is an elaborate and coordinated scheme to establish shell companies in the names of Darwan’s relatives and cronies, endow them each with licenses for thousands of hectares of land, and then sell them on to some of the region’s biggest conglomerates. Those involved stood to profit to the tune of hundreds of thousands, possibly millions of dollars. If the plan was carried through to completion, it would transform almost the entire southern stretch of the district, below the hilly interior, into one giant oil palm plantation. If Darwan had his way it would be possible drive 75 kilometres east to west and 220 kilometres south to north through a sea of palm.

The scheme involved a cast of more than 20 people who appeared as directors or shareholders in the shell companies. They included members of Darwan’s family, associates from his time as head of a building contractors association, members of his election campaign team, and at least one person who said his name was used as a front.

“A lot of public officials, they didn’t want to bring Seruyan to life. They just wanted to suck it dry.”

Darwan’s wife, Nina Rosita, was a shareholder in one. His daughter Iswanti, who would go on to serve as a provincial politician herself, was a director and shareholder in one, a shareholder in a second and director of a third. His daughter Rohana was also a director. His son Ruswandi got a more prominent role, as director of several companies and a shareholder in at least one more. His older brother Darlen had two companies, his younger brother Darwis one. It stretched into his extended family, through Darwan’s nephew and the husband of his niece.

In total, we identified 18 companies that connected to Darwan. Three were incorporated several years before he became bupati. That shows that his interest in large-scale oil palm predated his political career, but that it had stalled: the companies remained inactive until after he assumed office. Two more were formed in 2004, a year into his reign, and then in early 2005 the real flurry of activity began.

Five companies cropped up in a two-day window in late January; another appeared two weeks later. We were able to determine the directors for all of the companies, and the shareholders for all but six.

Almost all of the companies involved at least one of Darwan’s family as a shareholder. His name did not appear on any of them, but Marianto came to the view that he was coordinating the scheme. “They’re like pawns on a chessboard,” he said. “Darwan moves the pieces.”

Most of the names were used sparingly. But some cropped up more often than others, and these would provide important clues as to how the scheme functioned. The first was Vino Oktaviano, who was named as a shareholder in three companies set up on the same day, and a director in one.

Nordin Abah, the local activist who carried out his own investigation of Darwan, happened to know Vino well; they sent their children to the same school and sometimes met for coffee. In the wake of the scandal around BEST Group and the national park, Nordin sought out the names behind Darwan’s permit spree. When he found Vino’s name, he challenged him over it. Vino told Nordin that Darwan had used his name, and that he had no actual role in the companies.

“He thought it was normal, that nothing would come of it,” Nordin told us at the Palangkaraya office of his NGO, Save Our Borneo. “He just didn’t want to take any responsibility for it.”

Vino worked as a building contractor, obtaining jobs from Darwan’s administration, and was a nephew of Darwan’s wife. The name of his boss, a confidante of Darwan’s from his days in a trade association, also appeared in company documents.

“You’re going to go to jail Vino, if this thing blows up,” Nordin recalled telling him. “They made me do it, Din.” Vino replied. “I was tricked.”

Where Marianto was a political insider, a mover and shaker in the logging game who soured on the man he once considered an ally, Nordin was a campaigner who hounded the palm oil companies ravaging Seruyan. He also had strong connections to and within the district. His uncle had served as the regional secretary, the highest position in its civil service. On Darwan’s trail, he set about tapping his own relatives in the bureaucracy for leads. He had managed to uncover most of the names involved, noting like Marianto that many of the addresses to which the companies were registered were either duds or owned by the bupati and his family.

“They’re like pawns on a chessboard. Darwan moves the pieces.”

Nordin observed that a plantation company would need to operate a factory to mill the fruit, and Vino “couldn’t even run a tofu factory”. He was adamant that other people had been used in the same way. “You might be a teacher, you might be a journalist, you might be a contractor — there’s no way someone like that can get a permit for a plantation,” Nordin explained. “You don’t know how to develop an oil palm company. And you don’t have the money. It’s just for selling. The story is, I use your name to make a permit to sell to someone else.”

The name Ambrin M Yusuf appeared as director of one of the companies. Nordin identified him as a confidante of Darwan from their time in the East Kotawaringin builders’ association. We tracked him down to his house in Kuala Pembuang, where he had recently returned after serving a jail term for his role as a bag man delivering cash in a local bribery scandal.

He admitted to being a political ally of Darwan, and said that intermediaries had asked him to put his name to the company. But he claimed, implausibly, that he had turned them down, and that the person named in the documents was another man with the same name. He nevertheless admitted that it was “normal” for a bupati to give permits to a family member.

Yusuf and Vino’s stories suggested that cronies were being used as fronts, potentially to keep someone else’s name — the true beneficiary — off company documents. Nordin and Marianto believed that other people whose names appeared were more complicit. They both pointed to a man named Khaeruddin Hamdat as a central figure.

Khaeruddin appeared as director of three of the companies, though never a shareholder. Marianto, Nordin and others identified him as Darwan’s “adjutant”. It is a term commonly used in Indonesia for the person who serves variously as the advisor, right-hand man and fixer for important politicians. Known as Daeng, an affectionate term for a man from his home island of Sulawesi, Khaeruddin was only in his mid-30s by the time the companies were formed. Nordin described him variously as the “boss in Jakarta” and Darwan’s gatekeeper, meeting with palm oil executives in a posh hotel in the capital. (Khaeruddin declined to comment for this article.)

“Because Darwan has to protect himself,” Nordin said. “No way he uses his own name to cut a deal.”

Most of those involved in the scheme proved to be elusive or declined to comment when they got a sense of what we were asking questions about. But one of the few people we knew for sure where to find was Hamidhan Ijuh Biring. He had been jailed for yet another corruption scandal, and we tracked him down to a prison on a main boulevard in Palangkaraya, the provincial capital.

“It’s just for selling. The story is, I use your name to make a permit to sell to someone else.”

Hamidhan’s name appeared as a director and shareholder of one of the 18 companies. He was also married to Darwan’s niece. He told us that he had set up the company and received a license from Darwan, but lacked the capital to develop a plantation. Darwan encouraged him to sell the company to a political ally in Jakarta who also served as director of an existing plantation company in the district. After the deal went through, Hamidhan received one portion of the payment but the second, he later discovered, went directly to Darwan. “It turns out Darwan was inside, telling him, ‘No need to pay Hamidhan’,” he said bitterly.

Before his relationship with Darwan soured, Hamidhan was an insider, campaigning with him ahead of his 2008 re-election bid. He corroborated Nordin and Marianto’s claim that Khaeruddin Hamdat served as Darwan’s adjutant. He said that whenever he met the bupati, Khaeruddin was there with him.

The sequence of events after the shell companies were formed tells us two things. Firstly, that the intent was never for the founders to develop the plantations themselves. Between December 2004 and May 2005, Darwan gave 16 of the companies permits for plantations. By the end of 2005, at least nine of them had been sold on to major palm oil firms for hundreds of thousands of dollars. It seems implausible that a series of interconnected people, in many cases family members, would concurrently form companies only to decide that they lacked the capacity to run them. The sole explanation is that they were set up to be sold, endowed with assets from Darwan.

Secondly, it tells us there was a strong degree of coordination in the ways they were both formed and sold. Most of the companies were established within a small window of time, many of them just days apart. Several were also sold within a small period of time some months later.

Eight of the shell companies were bought by the Kuoks in late 2005. Darwan’s family and cronies would eventually derive just under a million dollars from the deals with the Malaysian billionaires. In the scheme of things, it was a pittance, a fraction of what the Kuoks would earn from the plantations if they were developed. But in these deals, the shareholders linked to Darwan also kept a 5 percent stake in each of the companies, which could make each of them multi-millionaires in their own right.

The evidence Nordin obtained of the connection between Darwan’s family and the companies sold to the Kuoks was first outed in an international NGO’s report, in June 2007. It was just two weeks before two of the Kuok family companies were merged under the name Wilmar International, forming what is now possibly the world’s largest palm oil firm. Wilmar was already attracting heat for a litany of illegalities and social and environmental abuses across its plantations. The same year, a consortium of NGOs filed a complaint with the World Bank ombudsman, providing evidence, later upheld, that the institution had breached its own safeguards by financing the controversial firm.

Though the allegations regarding Darwan’s licenses only received a brief mention in the NGO report, the whiff of a corruption scandal may have proved too much. In an email responding to questions for this article, Wilmar told us that it had decided to mothball the companies issued by Darwan after engaging with NGOs. It declined to mention when the decision was made, and continued to list the companies in its annual reports as late as 2010.

Triputra Agro Persada, presided over by the young Arif Rachmat, bought seven companies from the bupati’s family. (Triputra declined several requests for an interview, directed to Arif Rachmat, although they did respond to some questions via email.) Four of these companies were later mothballed, but the other three, which were developed, linked directly to Darwan’s son Ruswandi. By the end of 2007, two of these companies had already begun clearing vast tracts of forest, peat soil and farmland. Triputra would emerge as one of the worst oil palm companies in Seruyan for people and the environment, in a crowded field.

Marianto was certain that Darwan had betrayed his constituents. By the time he met the whistleblower in early 2007, the plantation boom was fully underway, yet the average Seruyan resident remained worse off than in the era of logging. Now, the only option for many farmers was to earn a pitiful wage as a labourer on one of the estates. They were losing their farmland, the destruction of forests deprived them of food and other resources, and fishing grew increasingly difficult in polluted waters. Above all, the promise that the mega-plantations would be accompanied by smallholdings for the farmers, thereby cutting them in on the spoils, went undelivered.

Marianto placed the blame for the problems that were emerging at Darwan’s door. The bupati had the power to revoke licenses as well as issue them; if he was motivated to do so, surely he could force the companies to deliver for Seruyan’s people? The leak confirmed that his motivations lay elsewhere.

Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission, the KPK, born after the fall of Suharto, was emerging as a new force in the fight against graft by public officials. In June 2007, as Indonesia passed Malaysia to become the world’s top palm oil producer, Marianto packaged up his findings and travelled to Jakarta to deliver them to the agency in person.

As 2007 drew to a close, delegates from around the world arrived on the Indonesian island of Bali for the 13th annual UN climate change conference. The fate of the earth’s forests was firmly on the agenda. But in the high rises of Jakarta a different game was afoot. Four days before the UN summit began, as Darwan Ali prepared to campaign for his first direct election, his son Ruswandi stepped into the Kadin Tower for his meeting with Arif Rachmat, to cut another deal with Triputra.

After Suharto resigned there was optimism that the grand larceny of his regime would recede. It was hoped that the rapid decentralisation of authority would shift accountability for political decisions close to the people affected by them. But by 2008, the year of the first direct vote for bupati of Seruyan, it was increasingly clear that corruption had simply been moved down through the system.

In a forthcoming book entitled Democracy for Sale, political scientists Ward Berenschot and Edward Aspinall write that Indonesia’s districts came to be dominated by “a netherworld of personalized political relationships and networks, secretive deal making, trading of favours, corruption, and a host of other informal and shadowy practices.”

Elections were a cornerstone of this game. They had become hugely expensive affairs, with the cost proportionate to the amount of power over lucrative projects or natural resources the winner could dole out to supporters. For bupatis governing land- and forest-rich districts, they routinely ran into the millions of dollars. Berenschot, Aspinall and other academics who have studied Indonesian elections over the past two decades have identified a uniform, systematic process by which candidates spend their money.

First, they pay off officials in their political party to ensure their selection as a candidate. Next, they recruit an extensive group of political activists and influential figures to join their “success team”. Then they provide cash for the success team to buy up the support of local powerbrokers — village chiefs, religious leaders and the heads of sports clubs who enjoy extensive influence in some places. These individuals in turn solicit the support of people within their own spheres of influence.

Candidates organise expensive rallies and concerts, paying for popular singers to perform and handing out free meals. Finally, they engage in what is generally referred to as a “dawn attack”, organising dozens of supporters to hit the streets and knock on doors, handing out money directly to voters to solicit their endorsements. This, Berenschot told us, is the costliest part for candidates. He estimated the price of running for bupati at between US$1.2 million to US$6 million.

The funds come from local businesspeople and contractors, in the expectation of rewards if the candidate is successful. “After the election, it is payback time, and campaign donors and workers can expect to be rewarded by winning candidates with jobs, contracts, credit, projects and other benefits,” write Berenschot and Aspinall. But they also note that incumbents start from a position of advantage, having built up a “war chest — typically by engaging in various forms of corruption,” for the next election. “The exchange of favors and material benefits at every stage of the electoral cycle is so pervasive that it is apt to think of democracy in Indonesia as being for sale.”

By his own admission, Hamidhan Ijuh Biring, the husband of Darwan’s niece who obtained a license from the bupati, played such a role in the 2008 campaign. At the time, Hamidhan told us, he already believed that Darwan had ripped him off. But he still thought he could be rewarded if the incumbent retained his seat, and he was in on the winning ticket.

Hamidhan told us he contributed US$50,000 to Darwan’s campaign ahead of the election. He understood he was joining a cast of characters who had benefited personally from the bupati’s patronage: building contractors to whom Darwan had handed lucrative projects without public bidding, which was then legal; plantation bosses who could instruct their workers, many of them migrants from other islands, to vote for the incumbent. In the dawn attack, he said, cash worth US$10 to US$25 would be attached to the back of instant noodle packets and distributed to voters.

“The exchange of favors and material benefits at every stage of the electoral cycle is so pervasive that it is apt to think of democracy in Indonesia as being for sale.”

In February 2008, Darwan won the election and resumed his position as bupati of Seruyan for a second five-year term. To celebrate, his brother Darlen organised a concert near the lake, featuring the singer Rhoma Irama, known as the King of Dangdut. No one had stood a chance of making a meaningful challenge to Darwan given the spending advantage provided by his hold on the bupati’s chair. He prevailed despite a brewing storm, as resentment of the plantations grew. The consequences of the land deals he presided over would soon become fully apparent to the people of his district.

Part Four: Resistance

One night during Darwan’s second term, a farmer named Marjuansyah, who lived in the village the bupati had grown up in, had an unsettling encounter with the police. For two years he had nursed a small patch of oil palm east of Lake Sembuluh, and hundreds of saplings were now close to bearing fruit. But his land also fell within an area licensed to one of the companies Darwan’s son Ruswandi had sold to Triputra.

The police told Marjuansyah that they had come on company business. Triputra, they said, would pay him five million rupiah, around US$550, for each of his nine hectares. The cash would not last long, while the palms he had cultivated could provide him an income for the rest of his life, a security net as he entered old age. He did not want to sell, but felt uneasy about refusing a firm whose approach had been made through the police. Hoping to put them off the trail, he later told them he could accept no less than twice what they were offering.

Instead, he told us, Triputra found other people to stake a false claim to his land, and paid them for it. Pliant local officials vouched for the transaction. The company ran bulldozers over his farm — smallholder oil palm is typically inferior to corporate-grown trees — and demolished a cottage he had built. “I reported it to the police,” Marjuansyah told us at a friend’s home in the village, clutching a blurry photo of his former dwelling. “But there was no reaction.”

A similar fate befell many of the people of Seruyan as plantation firms advanced through their farmlands and the surrounding forests. It was not uncommon for the companies to offer some money for their land, presumably in the hope of heading off resistance. But it was not, as Marjuansyah found, a negotiation, and there was little option to refuse.

The farmers were at a disadvantage because the state did not recognise their land rights. Some had certificates issued by village chiefs but these were legally precarious compared to the companies’ state-sanctioned licenses. As Marjuansyah also found, they could be forged or manipulated. Many land claims were overlapping, a situation that had not troubled village life when there was no commercial pressure on land, and they could be resolved through customary law. When the companies arrived, they ignited and exploited these disputes, buying land from whomever would sell it first.

The presence of the police in negotiating with Marjuansyah was not an isolated incident. In other cases, they took a clear and partial position in protecting the companies’ interests. A farmer named Wardian bin Junaidi told us how Triputra’s same subsidiary tore down his rambutan and durian fruit trees. His appeals to the company were ignored.

“I got fed up with continually petitioning them,” he said. “So one day I went and harvested some of that palm fruit myself.” He was arrested and imprisoned for several months. “I was accused of stealing. Really, those people are the thieves. But the law is selective. It’s not for us poor people. It’s the companies that have the money.”

From the earliest days of Indonesia’s palm oil industry, the government had sought to strike a balance between ceding land to large companies capable of developing viable plantations, and ensuring that nearby communities benefited. Through the 1980s and 1990s it experimented with various models, involving both the state and private sector. Most commonly, firms were required to equip local farmers with smallholdings planted with oil palm. Just a couple of hectares of mature trees could transform the lives of an impoverished family in rural Indonesia.

The proportion of land that companies had to provide varied. Cede too much to the firms and the communities would not benefit; too little and the investment would be unappealing. By 2002 the prevailing regulation was ambiguous over how companies were to support local farmers, but clear that they had to do it. This was the regulation that gave bupatis power over licensing, and also the authority to revoke permits if companies failed to “grow and empower” local communities. In 2007 the rules became more concrete, requiring companies to provide, plant and hand over an area of smallholdings equivalent to a fifth of their license.

Every company greenlighted by Darwan was bound by these rules, but across the board they failed to comply. From the moment the Kuoks and Rachmats came into the district, in the early 2000s, they had promised smallholdings. Into Darwan’s second term, their failure to deliver caused growing unrest.

“I was accused of stealing. Really, those people are the thieves. But the law is selective. It’s not for us poor people. It’s the companies that have the money.”

If the early land grabs were a cold hard shock, the dearth of smallholdings was a sting that lingered. Without them the communities were left out of the riches generated by the plantations, which were concentrated in the hands of the billionaires who had become the district’s biggest landowners. The villagers had lost their farms, the rivers had become polluted, the best jobs on the plantations went to outsiders seen as more skilled, and day labour picking fruit paid too little to live with dignity.

As the villagers’ protests fell on deaf ears, it became increasingly clear that Darwan was not only representing the companies’ interests, but also wielding his control over the state in support of the firms. When Triputra sparked alarm with a plan to build a processing facility upstream of Lake Sembuluh, residents who complained were met with threats from the bupati himself.

“In 2010, he came to our village for a religious event and said, ‘no one should oppose the mill or there will be trouble,” one villager told an NGO. “‘If you work in government or plantations, then you will be fired’.” Darwan reportedly installed new chiefs in villages that opposed plantations, eroding the potential for resistance through formal institutions.

At the beginning of Darwan’s second term a heavyset, outspoken man named Budiardi was elected to the district legislature with, as he described it, “a mandate to struggle for the people’s rights against the company.” Budiardi came from Hanau subdistrict, where the BEST Group had set up in the national park and in the villages around it. Yet he soon came to the view that it was futile to try to change the system from within. Darwan’s party dominated the parliament; the speaker was his nephew. “It was useless to oppose Darwan’s policies,” Budiardi told us. “The bupati controlled the parliament.”

James Watt, a stoic farmer from the lakeside village of Bangkal, had bought into Darwan’s pledge to make the plantations work for the people, before his land was taken by the Sinar Mas Group, an Indonesian conglomerate founded by the billionaire Widjaja family. “All we got was oppression,” James told us. “Clearing our land, dumping waste in our rivers. We never imagined it would be like this.” As the companies pushed forth, Darwan didn’t lift a finger. “It was always empty promises with him. I think he saw being bupati as his chance to make as much money as possible.”

As the futility of opposition through the state — village institutions, police, parliament, and bupati — dawned on the farmers of Seruyan, they began to take direct action. A man named Sadarsyah who claimed his land was grabbed by Triputra became a symbol of the unresolved conflicts in early 2011, prompting villagers to block a company road for days. Triputra accused him of fraud and reported the protesters to the police.

“It was useless to oppose Darwan’s policies. The bupati controlled the parliament.”

Meanwhile in a Wilmar subsidiary, hundreds of villagers shut down a main road into the concession, where mill effluents continued to pollute local water supplies. Anti-riot police had by then become a frequent sight in the plantation. When an NGO team made a research trip to one of Wilmar’s plantations in 2012, among the first things they saw was a soldier with an M-16 assault rifle.

The prospect of a prosecution by the KPK hovered over Darwan. The anti-graft agency visited Seruyan in 2008, following up on Marianto’s report only after the bupati was locked in for a second term. They searched government offices for data over several trips to Kuala Pembuang, the seaside district capital, according to Marianto. (The KPK declined to comment on Darwan’s case.)

At one point, they held a meeting with Darwan’s aide and a coterie of local figures, Marianto included. “Don’t just come and look around,” Marianto recalled urging them. “We hope the KPK can bring about the result desired by the people.” But as the second term wore on, the investigation seemed to go nowhere.

Nordin Abah, the activist who did his own investigation of Darwan, also reported him to the KPK. He was in contact with the agency’s leadership throughout his second term, but a case never transpired. Nordin had the option of reporting him for corruption to the police or attorney general’s office, in addition to the KPK. But he told us that would have been “pointless” — they were just as crooked as Darwan.

“All we got was oppression. I think he saw being bupati as his chance to make as much money as possible.”

Nordin also feared he could have been “criminalized”: arrested for an offense he didn’t commit. He said he received a threat against his children, sent to his phone. “Nordin, if you come here again, if you stay in Seruyan, you’d better think about your little son,” he told us, taking the voice of his intimidators. “That upset me, those threats about my son. If it’s just me no problem, but if it’s my son I’m worried.” Nordin passed away from hypertension in June this year, at the age of 47.

Toward the end of July 2011, tensions in Seruyan came to a head. Thousands of villagers from across the district descended on the seat of Darwan’s administration in Kuala Pembuang, pitching tents outside the parliament building and demanding an audience with the bupati. The protesters represented 27 villages, and had come to air the twin grievances of land grabs and the failure to provide smallholdings. One of the coordinators was James Watt, the farmer from Bangkal who had lost his land to the Sinar Mas Group. They were accompanied by sympathetic members of the local parliament, including Budiardi. The people unfurled their banners, set up a general kitchen and declared their intent to stay put until Darwan came to meet them.

Days later, Darwan finally emerged from the door of the parliament building. Stepping out onto a raised veranda, he looked down upon the protesters surrounding it. He had deep jowls and a lopsided smile that gave him a sardonic expression. He wore his dark, button-down bupati’s shirt and a black peci, a Muslim cap. He was accompanied by an entourage of aides and other government figures, including the chief of the local police.

James Watt and other protest leaders used a megaphone to recite their demands. They wanted the bupati to use his authority to push the companies to resolve land conflicts, and force them to provide a fifth of their land for community plantations. Darwan listened, and replied that he welcomed the arrival of the people and would try to convey their aspirations to the companies. But he said it would be impossible for companies to provide smallholdings from within their plantations as they were not legally required to do so. They shouted him down, yelling at him that he was a liar, as James remembers it. Darwan raised his hand to try to quiet them. They kept on shouting.

“It embarrassed him,” James said. “He decided he didn’t want to talk anymore, so he turned around, went inside and left out the back.”

The protest took place during a sharp escalation of conflicts over land across Indonesia. The following month, a murky conflict in Mesuji, southern Sumatra, became the centre of national attention after a retired general screened a video at a parliamentary hearing in Jakarta, purportedly showing evidence that the security guards of an oil palm company had beheaded farmers.

A few months later, hundreds of villagers occupied a port on Sumbawa island in defiance of a mining permit issued to an Australian firm. After five days, riot police opened fire on the blockade, killing two teenagers. The same month, 28 farmers from an island off the Sumatran coast sewed their mouths shut to protest a plantation license that covered more than a third of their island. By the years’ end, at least 22 people had died in hundreds of actions across the country.

The protest took place during a sharp escalation of conflicts over land across Indonesia.

Pundits chided protesters for “disregarding their democratic right of bringing grievances to their elected representatives” in favour of “street power,” as a Jakarta Post editorial put it. Budiardi, the local parliament member from Seruyan, saw it differently. “We tried to communicate with them about resolving the land conflicts and partnering with the people,” he told us. “But I think we can’t do anything if the bupati doesn’t care about what the people want.”

That December, 11 people from Budiardi’s home subdistrict of Hanau entered a BEST Group plantation to commit their own act of vandalism. Fed up after years of petitioning the company, they used a truck and rope and ripped out several of its palm trees by the root. Everyone who participated was imprisoned for several months. Budiardi was not there, but he had organised protests in front of the company’s office, and was now labelled a “provocateur.” A warrant was issued for his arrest. Ignoring the summons, Budiardi travelled to Jakarta with a delegation of Hanau residents for a hearing at the national parliament. After a month or so as a “fugitive”, Budiardi too was arrested. He was tried and sentenced to four months in prison.

For Budiardi, it was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Upon completing his prison term and returning home, he emptied out his file cabinet, took copies of permits Darwan had issued and other documents behind his house, and set them on fire. “I lost my will to continue this struggle,” he told us. “I didn’t want to have anything more to do with it.”

If grappling with the plantations left Budiardi resigned to defeat, it only stiffened James Watt’s resolve. He would need it, for the frontrunner to replace Darwan after the end of his second and final term was none other than the bupati’s own son, Ahmad Ruswandi.

By the time of the election in Seruyan, in April 2013, the post-Suharto era was buckling under the weight of local leaders who had honed the manipulation of democracy into a fine craft. Entire clans swept into the halls of government, as district chiefs sought to continue their reign beyond term limits, installing their spouses, siblings, cousins and children into political office. Later in 2013, the arrest of Indonesia’s top judge for taking bribes to settle election disputes would propel the issue of dynastic politics into the national spotlight. But when Ruswandi stood for bupati, it was already a pressing concern for those in Seruyan who could barely stomach the thought of another five years of rule by Darwan’s family.

“The way the people saw it, it was like changing the cover on your phone,” said Wardian, the farmer who had been jailed for stealing palm fruit in retaliation for the company grabbing his land. “Underneath, the machine is the same.”

Based on the usual rules of the game, Ruswandi looked like a shoo-in. Every one of the 12 parties with a seat in the local parliament had taken its place behind him. His main challenger had been forced out of the race when one of the parties withdrew its support and backed Ruswandi at the final hour. The head of its chapter in Seruyan expressed confusion at the decision, which had been made at the provincial level.

“The way the people saw it, it was like changing the cover on your phone. Underneath, the machine is the same.”

Ward Berenschot, one of the authors of Democracy for Sale, said that money routinely comes into play when candidates are seeking the backing of political parties, from which they need a measure of support in order to run. Parties can demand up to one billion rupiah, roughly equivalent to US$75,000, for each parliament seat they hold. Ambrin M Yusuf, the man who claimed he narrowly avoided being involved in the licensing scheme, was on Ruswandi’s campaign team. He told us that Darwan had stitched up the support for Ruswandi himself. “Haji Darwan took all the parties,” he said, using an honorific as a mark of respect. “It was bought and paid for at the province.”

Darwan was said to be so confident in his son’s chances that he boasted it would make no difference if an orangutan were his running mate. But as Ruswandi campaigned in the villages that had experienced his father’s form of development for a decade, he might have seen reason to take pause. Face to face with Wardian, he heard his path to victory might not be as clear as he anticipated. “You can’t rely on your money to win,” the embittered farmer warned him.

Darwan’s confidence proved to be misplaced. A grassroots movement swelled behind the only challenger, Sudarsono. Without the backing of a party, he had to stand as an independent, requiring him to collect thousands of signatures in order to run. Sudarsono was a member of the provincial parliament, while his candidate for vice bupati, Yulhaidir, had accompanied protesters in the massive 2011 demonstration as a member of Seruyan’s parliament. Key figures from the event, such as James Watt, backed the campaign and set up volunteer posts in their homes from which to organise.

The independents ran on a platform aimed squarely at the palm oil industry, signing a pledge that if elected, they would push the plantations to resolve land conflicts and provide smallholdings. It resonated with voters who felt betrayed by the man in whom they had once placed their faith. Sudarsono and Yulhaidir were announced the winners, taking 53.65 percent to Ruswandi’s 46.35 percent, and becoming the first candidates in Central Kalimantan to win a race for bupati as independents. Ruswandi accused the victors of cheating, but lost his appeal in the Constitutional Court.

Darwan was said to be so confident in his son’s chances that he boasted it would make no difference if an orangutan were his running mate.

The era of Darwan Ali was over. While the devastation his land deals had already triggered would continue, he had lost his power to do further damage. At least for the time being.

Part Five: Corruption

Tothe handful of observers who were aware of what Darwan had done, it was clear that he had abused his office to make money for his family, while inflicting considerable harm on the people he was elected to serve. The KPK investigators circled around the case for years, so why didn’t they pounce?

The investigators involved, who have all since left the agency, were either unwilling or unable to comment for this article. We sought answers through interviews with current KPK officials, NGOs and academics focusing on anti-corruption efforts in Indonesia, and our own research on other KPK cases.

The easiest way to prosecute a corrupt official under Indonesian law is to catch them red-handed accepting a bribe, usually after tapping their phone, which the KPK can do without a warrant. In 2012, the agency intercepted a payment to a bupati on the island of Sulawesi. The money came from a businesswoman seeking an oil palm permit. She initially claimed it was a “donation,” and then that she had been extorted.

Both the bupati and the businesswoman were imprisoned, but it is one of the very few licensing rackets the KPK has prosecuted. Tama Langkun, a researcher from Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW), a Jakarta-based NGO that helped Nordin Abah pursue Darwan, drew a comparison with Seruyan. “In my view it’s the same,” he told us. “The difference is that [in Sulawesi] they caught them in the act.”

Seruyan involved a more complex ruse. Rather than demand cash in exchange for permits, Darwan’s friends and relatives created shell companies that served as vehicles for making money from oil palm firms. This avoided the more obvious offense of bribery. But Indonesian law includes a broader definition of corruption, provided the case can fulfil three criteria. Firstly, the suspect must have abused their power; secondly, they must have done so with the intention of “enriching” themselves or someone else; thirdly, they must have caused “state losses,” meaning a monetary cost to the government can be determined.

It seemed self-evident that Darwan had acted with the aim of enriching his family and cronies. They had made more than a million dollars up front from permits he provided them. Similarly, there seemed to be a strong case he had abused his power. The permits Triputra bought from his son were a case in point; there is evidence they may have violated a range of laws during the course of their operations, as a consequence of Darwan’s light-touch regulatory regime.

The third criterion, state losses, may have proved a sticking point. When it comes to skimming money from budgets or contracts, it is easy to calculate the drain on public coffers. Indeed, it is just this sort of crime for which most bupatis are arrested. On the other hand, losses arising from the crooked issuance of a permit to log a forest, plant oil palm or mine coal are harder to measure. If the companies pay taxes, there is no obvious cost to the state. “This is the basic problem of why the number of natural resource corruption cases processed by Indonesian law enforcement is so small,” said Lais Abid, another ICW researcher.

There was another obstacle to prosecution unrelated to the law. Overstretched and understaffed, the KPK’s backlog of complaints topped 16,000 in 2008, the year after Marianto met the whistleblower in Kuala Pembuang. In 2007, it completed investigations of just 19 cases. It is also constantly under attack from rival institutions. In 2009, as Nordin discussed Darwan with the KPK’s top brass, the agency was embroiled in a feud with the national police and attorney general’s office that culminated in its chairman and two of its deputies being framed for murder, extortion and bribery. Dimas Hartono, a Palangkaraya-based activist who worked with Nordin, argued that the campaign to undermine the KPK distracted from Darwan��’s case.

The KPK is Indonesia’s most trusted institution, and most feared — it has never lost a case it has taken to court. But the agency holds dear to the mystique created by its perfect record, making it reluctant to proceed with any case in which a conviction is uncertain. It also cannot drop an investigation once it has begun, a clause embedded in the law to prevent defendants from paying their way out of trouble. But the rule, ICW’s Langkun believes, has had the perverse effect of scaring the agency away from more complex cases.

In recent years, ICW has reported 18 cases that “resemble Seruyan” that it believes were not processed for lack of a clear kickback to the officials involved. “Frankly, we’re disappointed,” Langkun said. “It’s made things very difficult for us.”

Darwan may also have been perceived as too small a target to merit the resources it would have required to take him down. The KPK focuses more on “big fish” in the capital than bupatis from the outer islands. Whether it deprioritized the case because he was too small a catch, or because the state losses were not clear enough, it highlights a gaping hole in the agency’s ability to prevent precisely the kind of corruption that has the biggest impacts on Indonesia’s forests and its millions of rural people.

In theory, an alternative pathway exists: Darwan might have been reported for nepotism. Nepotism is defined similarly to corruption, but a viable case does not require proof of state losses. The glaring caveat is that the crime falls under the jurisdiction of the police and attorney general’s office, whom Nordin believed would have asked Darwan for money to drop the case. Jimly Asshiddiqie, the founding chief justice of Indonesia’s Constitutional Court, echoed this view. “In practice, we have a problem with these traditional institutions,” he told us. “They are not enforcing the law; they’re actually protecting the companies.”

There is a gaping hole in the agency’s ability to prevent precisely the kind of corruption that has the biggest impacts on Indonesia’s forests and its millions of rural people.

Jeffrey Winters, a Northwestern University professor who studies oligarchies in Indonesia and elsewhere, compared the legal system outside the KPK to “a light switch that can be turned on or off” by those with money or political clout. If the entire system operated like the anti-graft agency, he said, the country would be as corruption-free as Singapore. “The KPK has a relatively narrow anti-corruption mandate and capacity,” he said. “A large part of the corruption spectrum is outside the purview of the KPK. And that part of the spectrum is not effectively pursued.”

The legal system outside the KPK is like a light switch that can be turned on or off by those with money or political clout.

Whichever combination of flaws allowed Darwan to slip through the net, the fact that he did was symptomatic of a problem that stretched far beyond the borders of Seruyan. Across the archipelago, the control of the office of the bupati over natural resources, combined with the option of using proxies and shell companies to nefarious ends, has attracted politicians with the aim of consolidating power and wealth at the expense of their people.

“It’s a loophole,” said Grahat Nagara, a researcher at Auriga, an NGO that works closely with the KPK. “That’s how all the dynasties in Indonesia make their money.”

Part Six: Dynasties

Despite his son’s defeat in the 2013 election, Darwan’s family remained embedded in the political establishment in both Seruyan and Central Kalimantan province. Darwan moved to a new political party, which he now chairs at the provincial level. It is an influential position for trading support in elections. Last year, he used it to back the current governor, the nephew of a timber baron who plundered Tanjung Puting National Park, for a second term.

Darwan did not respond to multiple interview requests, delivered via text messages and calls to a number provided by his party’s office at the House of Representatives in Jakarta. At one point, he answered the phone, and promised to text us his email address so that we could send him our questions, but he never followed up. Neither did he reply to a letter outlining our findings and including a series of detailed questions, delivered to his party’s headquarters in Central Kalimantan.

However, on an afternoon in April this year, we tracked down his son Ruswandi to a sprawling house in Sampit where he spends his weekends. Members of the family occupy various positions of power in the district and province. Ruswandi’s consolation prize after losing the race for bupati was to replace his cousin as head of Seruyan’s parliament.

We met him in the courtyard of the low-slung house, behind a white gate manned by a guard, on a set of wooden benches in the shade. Flanking us were a pair of custom off-road vehicles emblazoned with the Harley Davidson logo. In the garage sat another four-by-four, a gift from his father. Ruswandi grinned as he peppered his nasal speech with jargon-derived English-isms, such as “efektif efisien”. Small and pudgy, he wore black-rimmed glasses, but forsook the peci cap he was often photographed with.

He was in good spirits, uninhibited by the social crisis that faced his district, in which he was now perhaps the second-most influential politician. In fact, it was not a crisis he recognised, as in his view the shift to plantations had benefited Seruyan. “If there wasn’t oil palm, nobody would know what to do, because the natural resources are all gone,” he said. “That’s why as I see it, things are pretty good.”

He acknowledged that there had been “pluses and minuses” to the rapid spread of plantations, but the solitary downside he could identify was that the district’s waterways were “not like before”. Nonetheless, he exonerated the companies surrounding Lake Sembuluh from driving its pollution. His novel explanation was that the people “bathe and poop in it”. “If there weren’t any companies, the lake would still be dirty,” he said.

“If there wasn’t oil palm, nobody would know what to do, because the natural resources are all gone. That’s why as I see it, things are pretty good.”

At first, he claimed that the palm oil industry had provided jobs for locals. Then he switched tack and claimed that the problem was that locals did not want to work in the plantations. In the era of logging, they had been accustomed to easy money from timber. Now they were “spoiled”, while migrant labourers were more “qualified” for what he called “the system of harsh living”.

With some prompting, he admitted that it would be difficult for communities to benefit from the plantations in the absence of smallholdings. “Hopefully there will be smallholdings,” he said. “Because it’s a pity for the people.” But he was not brimming with ideas for how to make it happen. One parliament member we had met, from a rival party, had been adamant that the government should threaten to revoke the permits of companies that withheld smallholdings. The best Ruswandi could offer were platitudes about “synergy”.

Ruswandi openly admitted that he himself had owned three companies sold to Triputra, the ones it had gone on to develop. When the subject was brought up, he named the subsidiaries unprompted. But he spun a false narrative in an effort to dissociate his family from the web of corruption they had created. He claimed that the companies were formed before his father took office, and that Darwan had never given them licenses.

Company documents and a government permit database show this to be a lie. But Ruswandi reached for it quickly. He was keen to create the idea that he had drawn a red line between his own role as a public official and business, a line that had in fact become irredeemably blurred by his family’s permit trading.

“As a representative of the people, I’m like a referee,” he explained with a large smile. “If I’m the referee, and I play too, that’s not fair. So I do business outside Seruyan. In Seruyan, I have no businesses. I’m purely a representative of the people.”

He insisted that all of the licenses issued by his father were clean. As evidence, he cited the fact that he had never been caught.

“If they weren’t clean, they’d have been flagged by law enforcement, right?”

Earlier this year, news reports indicated that Triputra had begun to distribute smallholdings in some communities that had waited years for them. Sudarsono, the current bupati, spoke at a handover ceremony in Baung village. “I know just how long the people have been fighting for their smallholdings, and now that struggle is finally bearing fruit,” he said at the event. “The people should be proud and grateful.” A pack of government officials gave a thumbs-up for the camera. In tow was Ahmad Ruswandi, in his capacity as head of Seruyan’s parliament.

Baung lies on the Seruyan River, which squeezes through a narrow strip of land between Triputra’s gargantuan estates and a protected area on the fringes of Tanjung Puting National Park. The plantations leave the village with a few hundred meters of land east of the river; the west is off limits.

On a hot and dusty evening, we sat down with Damun, a member of the village government. He painted a bleak picture of life in the plantation era. Locals could no longer harvest timber without being arrested for illegal logging. Fisheries had collapsed with the fouling of rivers. Much of their farmland had been ceded to the companies. The best jobs at the firms went to outsiders seen as more capable, while the pitiful rates paid to unskilled labourers were barely enough to survive. Still, he told us, “The people here all depend on the plantations”. They were the only game in town.

Three years earlier, residents of Baung and other villages blockaded the road into one of Triputra’s concessions, demanding that it resolve decade-old land grabs. Now Damun felt they were finally on the cusp of getting a piece of the oil palm pie. Triputra had earmarked some 3,000 hectares of smallholdings in four villages.

“We’ve been waiting for seven years. This is our last hope. God willing, the company can help us.”

But Sudarsono’s announcement had been somewhat premature. Most of the land the firm had slated for the communities lay in areas in which the forestry ministry did not allow plantations. The reality of Triputra’s photo opportunity was that the smallholdings were still stalled. Only a tiny portion had been planted.

“We’ve been waiting for seven years,” Damun implored us. “This is our last hope. God willing, the company can help us.”

As the farmers of Seruyan await their smallholdings, Arif Rachmat, CEO of Triputra Agro Persada, promotes an image of his company that increasingly diverges from reality. He trumpets himself as a dynamic and progressive young tycoon. In January he travelled to Davos, Switzerland, for the World Economic Forum, where he was chosen as a Young Global Leader, joining a community of high achievers that describes itself as “the voice for the future and the hopes of the next generation.” Dressed in a winter coat, he told a TV crew, “One of my passions is about improving farmers’ productivity and livelihoods as well as food sustainability.”

One of Arif’s subordinates told us in an email that Triputra adheres to regulations requiring companies to provide smallholdings equivalent to a fifth of their plantations. This is not true in Seruyan, and there is evidence that the social unrest caused by the company spreads across its land bank, into other districts in Kalimantan.

Today, oil palm covers more than a fifth of Seruyan’s land. Ninety-six percent of it is owned by the super-rich, including the Kuok, Rachmat, Tjajadi and Widjaja families. Profits flow out to the capitals of Jakarta, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur. Only a fraction of the taxes collected by the state find their way back to Seruyan.

“We’ve been waiting for seven years. This is our last hope. God willing, the company can help us.”

The oil palm is concentrated in the district’s southern half, where most of its people also live. Villagers’ access to land is tightly constrained by the mega-plantations. Lake Sembuluh and its waterfront villages are almost fully encircled. Its southern banks are claimed entirely by Triputra, whose estates also extend down along the Seruyan River, hemming in the villages dotted along it.

In a written response to questions for this article, Wilmar told us it was trying to provide smallholdings in Seruyan and had succeeded in some areas. But it also said its efforts had stalled because there was no land left. This is what has become of a vision of private sector-led development that would somehow benefit the poor: no land for the farmers, because the billionaires own it all.

Sudarsono, the great hope for Seruyan, has earned the quiet disappointment of those who fought for his victory in the polls, and who remain excluded from the palm oil riches. But he has succeeded in promoting Seruyan as a pilot for a new idea floated in the world of corporate sustainability, branded “jurisdictional certification”.