This month The Gecko Project and Mongabay published “Saving Aru,” an article revealing how the people of Indonesia’s Aru Islands thwarted a plan to turn much of their homeland into a vast sugarcane plantation.

To halt the project, they had to overcome huge odds. In Indonesia, a young democracy still recovering from three decades of military rule, companies usually succeed in their efforts to annex indigenous lands. The country has consequently become blanketed in concessions for plantations and mines that have provoked thousands of entrenched land conflicts.

Read Saving Aru: The epic battle to save the islands that inspired the theory of evolution

By the time the Aruese became aware of the sugarcane project, smoothed through in secret by a politician who was later jailed for corruption, it was nearly too late to stop it. If it went ahead, it would replace Aru’s rainforests with a sea of sugarcane more than half the size of Puerto Rico, destroying the existing livelihoods and food supplies of tens of thousands of people.

It would also send Indonesia’s greenhouse gas emissions, already among the world’s highest, skyrocketing.

To save Aru, its people and their allies needed to force the government to cancel the project. Here are some of the keys to their success.

1. They built an ‘information chain’ to take stories from the interior of Aru to the world

When the Aruese first learned of the project, they filled the streets of Dobo, Aru’s main town, in protest. But at first, they garnered no attention from outside the archipelago and had little means of communicating what was happening. Soon after the protests began, a team of activists in Ambon, the provincial capital, rallied to their cause under the leadership of an influential pastor named Jacky Manuputty. Jacky’s team set up a website, Facebook and Twitter pages, united by a catchy name for their campaign, one that lent itself to a hashtag: #SaveAru. But they lacked content to push out from Aru, 700 kilometres away across the Banda Sea. So Jacky sent a pair of Ambon journalists to Dobo to teach the local activists how to produce their own information to be fed into the social media machine.

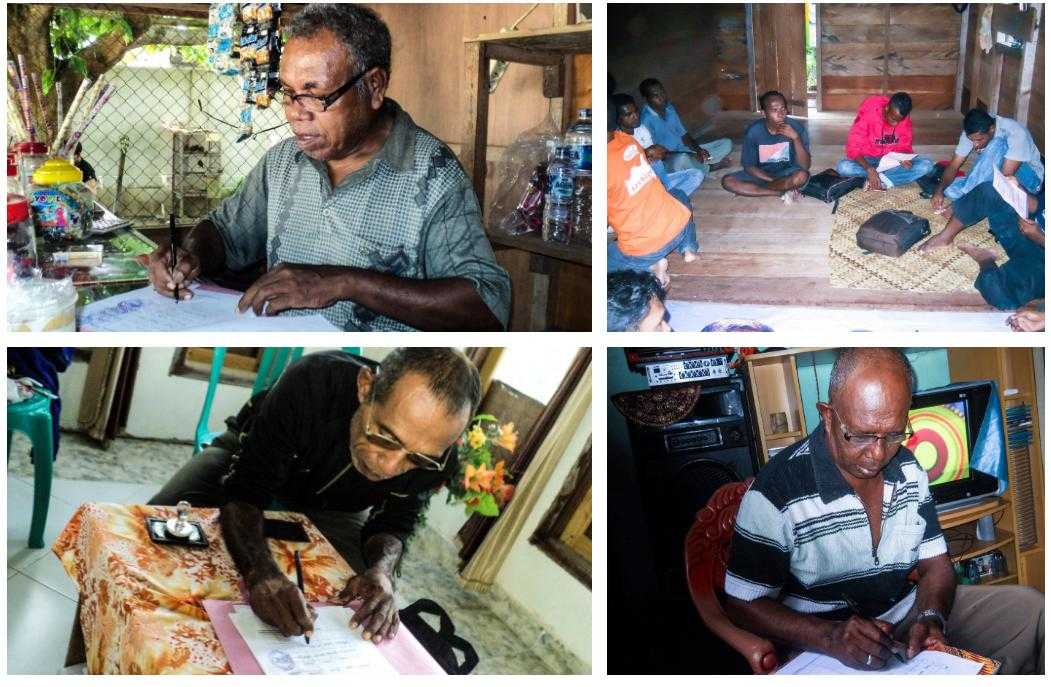

To get information from the front lines of the campaign to Ambon they faced a huge logistical obstacle: internet connectivity and even phone reception was patchy across Aru. So they went low-tech. Handwritten messages could be sent to Dobo by boat from the interior of Aru, where service was the worst; in Dobo, the Aruese could communicate with the Ambon team, generally via SMS, the cheapest option. Within weeks they were able to pump news, photos and graphics into the social media feeds. Just as importantly, social media allowed them to bring back messages from outside Aru that boosted the morale of the activists. They printed a giant banner comprised of photos of people from around the world shared on Twitter, holding up signs bearing “#SaveAru,” which they paraded through the streets of Dobo. Within months of the campaign starting they had a system capable of taking their story out to the world and bringing back powerful messages of support.

2. They carried out investigations

From the outset details of the sugarcane project remained sketchy. A mysterious firm called the Menara Group was said to be behind it, but they didn’t know how far it was along the licensing process, or the true scale. To fill in the gaps, Jacky’s team carried out their own investigations, working their contacts inside the government and scouring the internet for leads. They discovered the permits for the plantation had been issued to 28 different companies, all controlled by Menara, but with dozens of different directors and registered to phoney addresses in Jakarta. The activists suspected the complex corporate structure was a ruse designed to circumvent limits on the area of land a single company could control. Most damningly, they discovered that the district chief formerly in charge of Aru, Theddy Tengko, had allowed Menara to skip a critical stage of the permit process: Theddy had signed key permits before the company had completed environmental impact assessments (EIAs), in a brazen violation of the law.

3. They pressed influential institutions into backing their cause

The activists knew from the outset that it would be a tall order to directly influence the officials who had most control over the process. Some of these officials had already issued licenses, while the minister of forestry, Zulkifli Hasan, had indicated he would sign the final permits Menara still needed. So instead, the activists focused their efforts on other institutions that in turn might pressure the officials to halt the project. Chief among these was Ambon’s Pattimura University, and the academics within it who would help deconstruct the rationale for the project. They also secured the backing of the Protestant Church of Maluku, a powerful force in a deeply religious region. It was not a given that these institutions would support them. The campaign pushed them into taking sides by pointing to the growing groundswell of public support in Aru and online.

4. They debunked the pseudoscience behind the project

Although Theddy Tengko had illegally issued permits in the absence of EIAs, Menara later hired consultants to carry out the assessments. The resulting documents acknowledged the project would have huge negative impacts for people and the environment, yet argued these were outweighed by more-nebulous economic gains like “chances to work” and “business opportunities.” The Pattimura academics helped the campaign debunk these claims. They highlighted how existing livelihoods would be obliterated with the destruction of the rainforest, while jobs with the company would go to outsiders seen as more skilled or to an army of landless labourers brought in from outside. Endless chemical inputs required to grow such a vast stretch of sugarcane would contaminate the rivers and sea; the plantation would suck up Aru’s limited groundwater supplies; the unique animals that inhabited Aru, such as birds-of-paradise and cassowaries, would die out with the destruction of their habitats. The movement’s unstinting focus on this, as with the illegality, made it impossible for officials to approve the plantation on the basis of the consultants’ work. Ultimately, the minister of forestry commissioned his own review of the EIAs before deciding to cancel the project.

5. They established moles in government agencies

To gain ammunition for their information war, the activists sought to place informants in every major institution in Aru and Ambon. The investment paid off: a contact in a provincial government office provided them with copies of the permits underpinning the project; another source leaked them photos showing that members of Aru’s district parliament had visited Menara’s office in Jakarta multiple times. Their biggest scoop was an exposé of a secret meeting between the acting governor of Maluku province and Menara’s CEO at a naval compound in southern Aru. A local villager who was serving coffee at the meeting, and who sympathised with the movement’s caused, quietly snapped photos on his phone, and they found their way to the Dobo activists, who quickly published them online. At the meeting, another informant told them, acting governor Saut Situmorang had called Aru “just a stretch of reeds” and assured Menara it could begin operating within two months. News of the meeting spurred journalists in Ambon to cover the story, and they made Saut answer for his presence there.

6. They proved that opposition to the plantation was widespread

Even as anti-Menara protests rocked Dobo, most of Aru’s approximately 80,000 people, spread across several islands, knew little if anything about the project. Some villagers in the interior had encountered Menara’s survey team, which made grandiose promises of how the company would improve their lives. To counter this, the Dobo activists fanned out across the archipelago, over a period of months, to warn the people about the project and explain what it would actually entail. They gathered signed statements of rejection from traditional leaders and community members in 90 of Aru’s 117 villages. To prove that the signatures weren’t fabricated or forced, they photographed and filmed people signing them. They sent copies of the signature book to government officials even as the project’s backers tried to paint the Save Aru campaigners as a fringe group.

7. They rooted their movement in culture and local identity

The Aruese resistance was rooted in their indigenous culture and laws, which provided them with a powerful set of principles they could use to counteract the state’s power. This included laying down sasis, a form of customary prohibition, as a cornerstone of their protests, by women and even church ministers. Their culture is tightly bound with the natural world, which generated a deep-seated opposition to its destruction and pride in what they already had. This acted as a counterweight to the argument, presented to them by the government and company, that in order to “develop” they needed to give up their land and forests. They bluntly rejected the idea that they were “poor,” pointing to the wealth of natural resources that come from their rainforest, rivers and sea. This collision of views culminated in a meeting in Dobo, when a Menara Group representative warned the Aruese not to be “beggars with golden bowls.” The Menara Group, they replied, was the beggar.

8. Women were on the front lines

The women of Aru played a central role in the movement, taking to the streets for weeks on end to protests against the politician who green-lit the project, and subsequently the project itself. Women selling vegetables in the market donated food and supplies to the protesters. Older women joined the protesters and even faced off against police. They imposed specifically female sasis, customary prohibitions dictating that if they were violated, they were violating the women of Aru. “If you tear it down, it means you are stripping us naked, the women of Aru, from the birth mothers to the ones with the grey hair,” said Anatje Siarukin, a leader of the movement involved in placing a sasi at the entrance to the district parliament. “This is the cloth we use to cover ourselves. Whoever dares violate it invites bloodshed.” The prominent role of women, both in the streets and behind the scenes, was viewed as a powerful and critical component of the movement.

9. It was a genuine grassroots campaign

The support of people outside Aru, particularly the seasoned activists in Ambon, the provincial capital, was critical to the success of the campaign. As it reached a crescendo they were also joined by two major national advocacy groups — Forest Watch Indonesia and the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago (AMAN) — which helped to build pressure in Jakarta, the capital city, where the final decision over the project would be made. They attracted international attention, something cited by a government watchdog when it began to look into the case. But the Aruese worked with them in a way that did not diminish their role as the leaders of their own movement. The activists experienced the real risk that their movement could be dismissed as the work of outside “provocateurs,” or the result of an NGO campaign that did not have the real interests of the Aruese desire for development at heart. The movement struck a fine balance between making use of this support while maintaining control and, just as importantly, the perception of control. Everyone involved in the movement was not paid for their role, maintaining a “volunteer spirit” that Pastor Jacky Manuputty believed was critical to their success. “In many environmental advocacy movements, the community is represented by NGOs,” Jacky said. “This creates a situation where the people are very fragile. When pressure is inevitably brought to bear on the community, they can be split apart from below.”

10. They made it impossible to ignore illegalities in the permit process

Despite the clear illegalities the activists had unearthed, they were not confident the judicial system would respond effectively. Nonetheless, they made the suspect process a cornerstone of their push to have the government cancel the project. They consistently used it to challenge the legitimacy of the project, ultimately making it increasingly difficult for officials, including the minister of forestry, to issue the final permits Menara needed to activate its bulldozers without raising questions over their own propriety.

Read Saving Aru: The epic battle to save the islands that inspired the theory of evolution

To see other articles plus films and photos from The Gecko Project as they come out, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube. Sign up to our mailing list here. The Gecko Project stories are available in Bahasa Indonesia at our Indonesian site here.