As the palm oil industry swept through Indonesia over the past two decades, it transformed millions of hectares of land into plantations. Much of what was targeted belonged to, or was used by, indigenous and other rural communities.

Perhaps the key quid pro quo for them was the offer of “plasma” — in exchange for giving up control of their land, villagers would get their own portion of a plantation. The concept had been around since the 1970s. In 2007 it became a legal requirement for companies to provide a fifth of any new plantation for the benefit of local communities.

Around the same time, a new model became dominant. Instead of handing villagers their own plot of land to tend, companies said they would manage it on their behalf. The appeal was self-evident: they wouldn’t even have to work the land, but could just wait for the profits.

But for many communities, those profits never arrived. A decade or more later, they’re still waiting. Some are in millions of dollars of debt.

In our latest investigation, we delved into a dozen cases to find out why an apparently profitable industry was not delivering for rural communities, and the consequences for those who gave up their land.

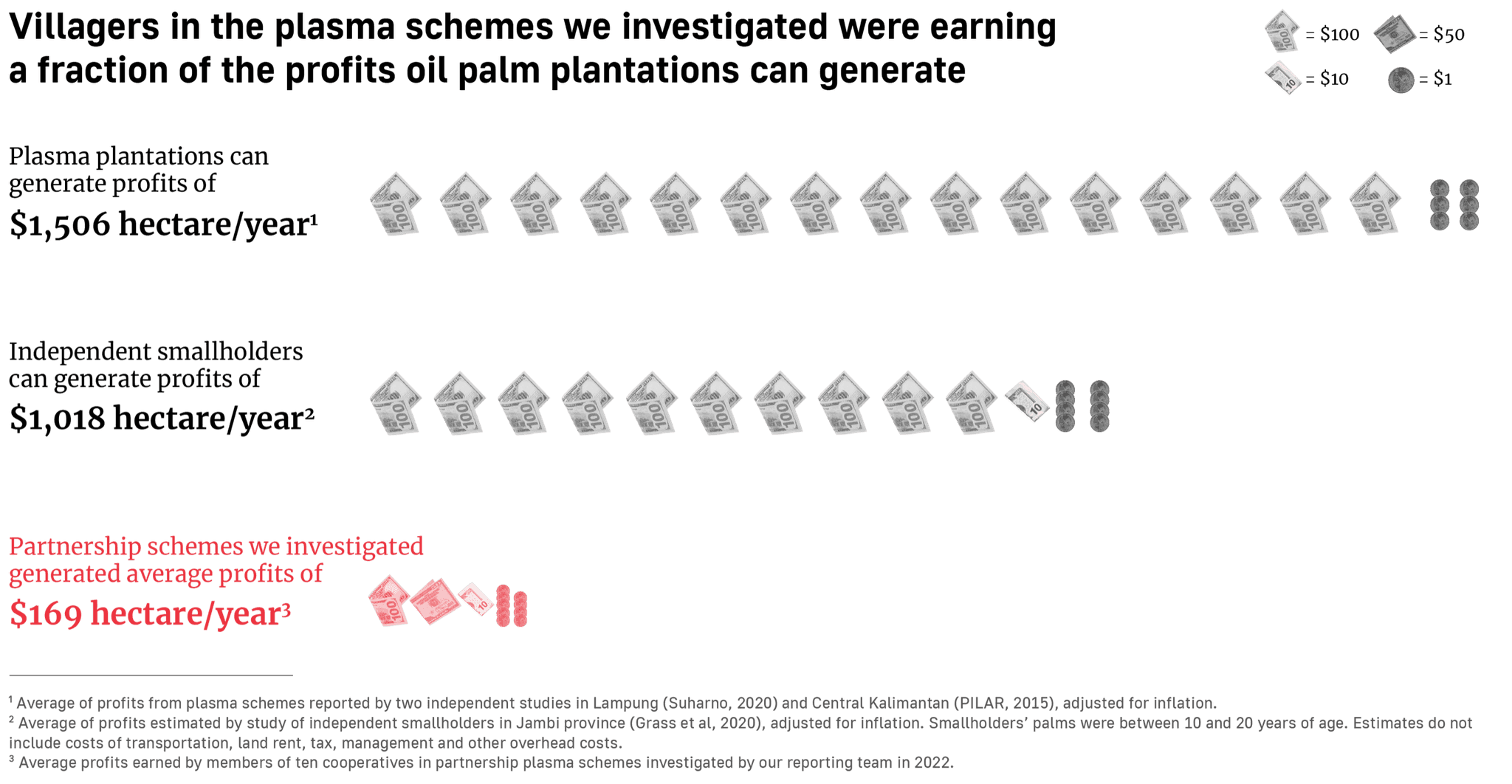

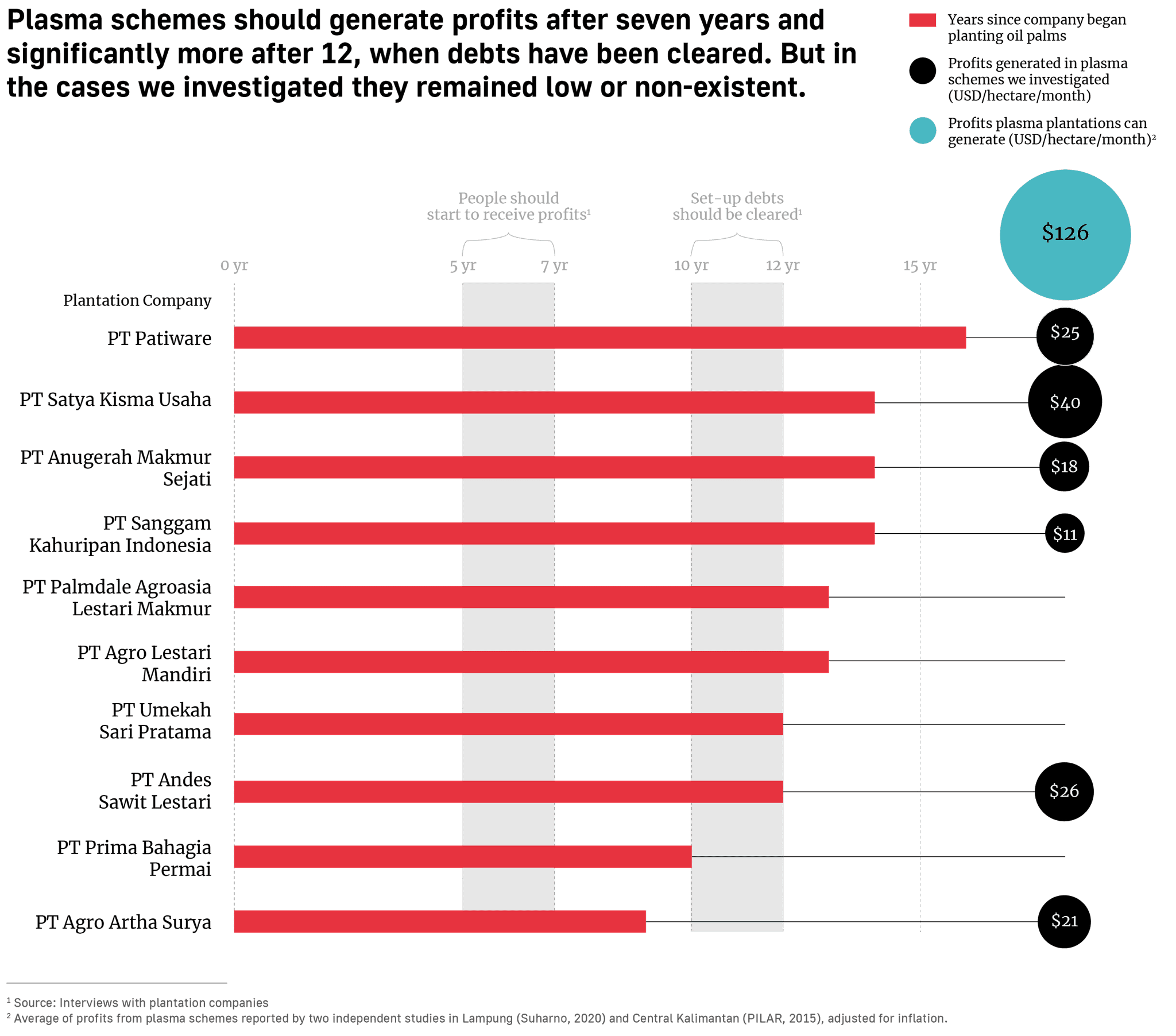

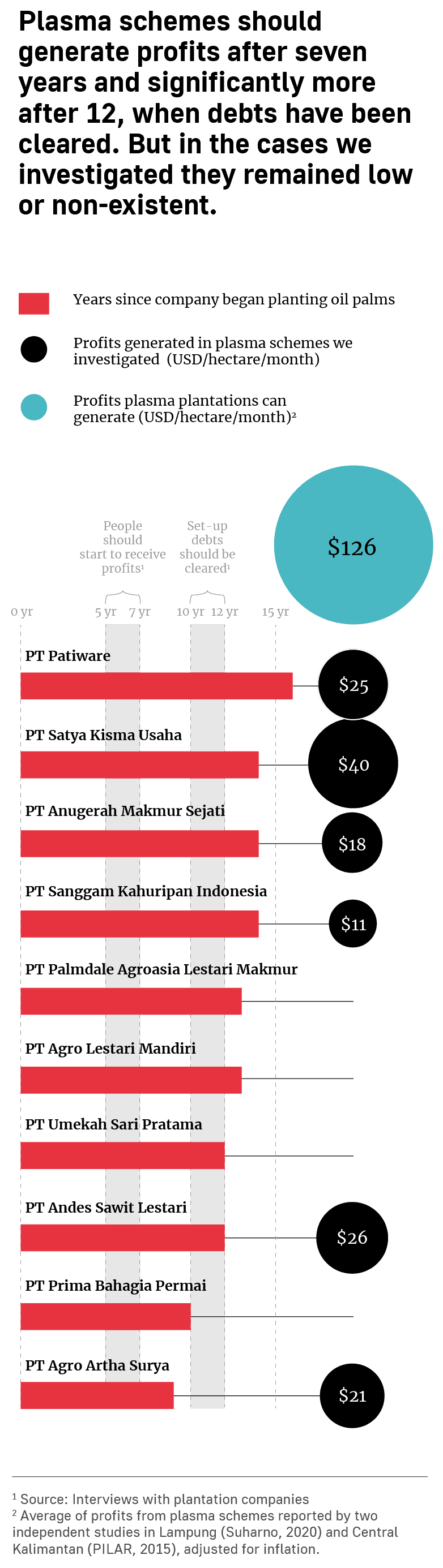

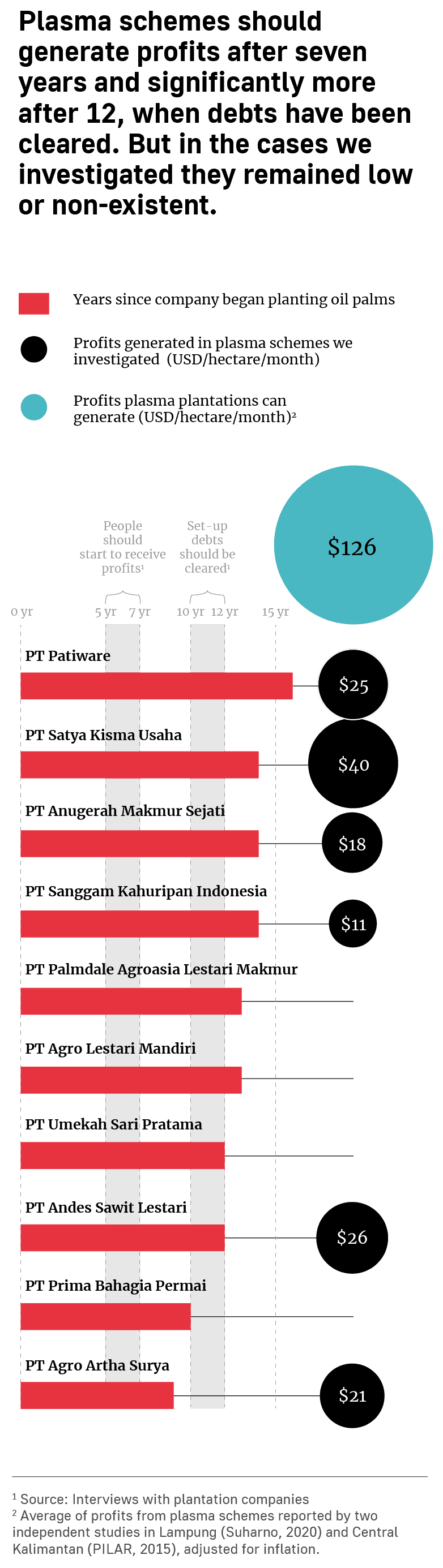

1. Communities in plasma schemes received far lower profits than plantations can generate

According to independent studies, “plasma” plantations can generate more than $1,500 in profit per hectare each year. Independent smallholders, who manage their own land without the support of companies, can earn more than $1,000 per hectare each year. But in the cases we investigated, people were earning just $169, on average.*

Some were making nothing at all more than a decade after they gave up their land, at which point the plantations should have been at their most profitable.

The companies we investigated included subsidiaries of two of the world’s biggest agribusinesses. There is evidence the problem stretches much further than the cases we looked at in depth, with a recent study finding widespread allegations that communities were being underpaid.

“What’s surprising is that we didn’t get anything. Not even one rupiah from that company in ten years,” said Martinus, a farmer from West Kalimantan. He had resorted to borrowing money from family members to fund his son’s education, after waiting in vain for the palm oil firm to pay him any profits. “They deceived us,” he said.

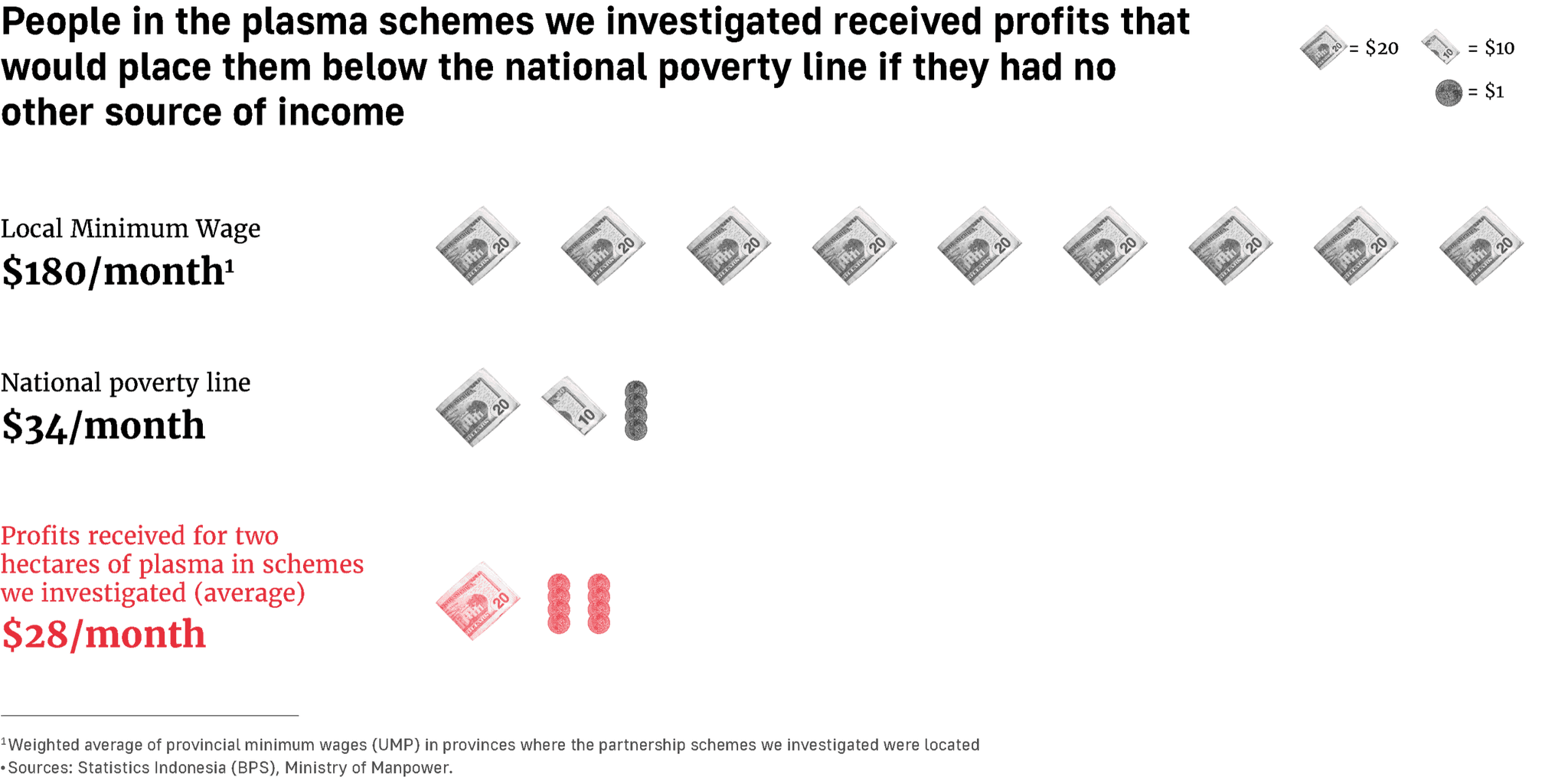

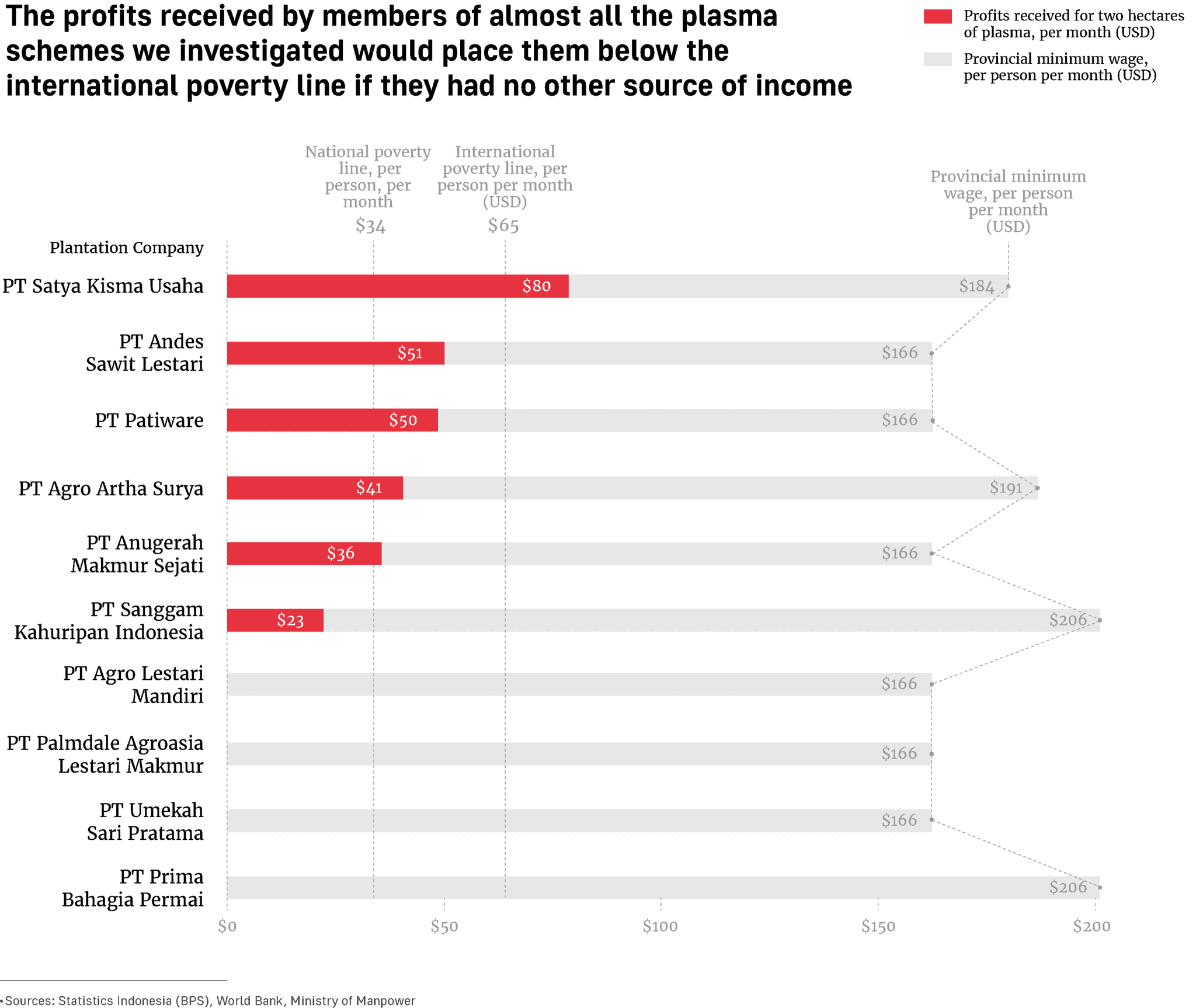

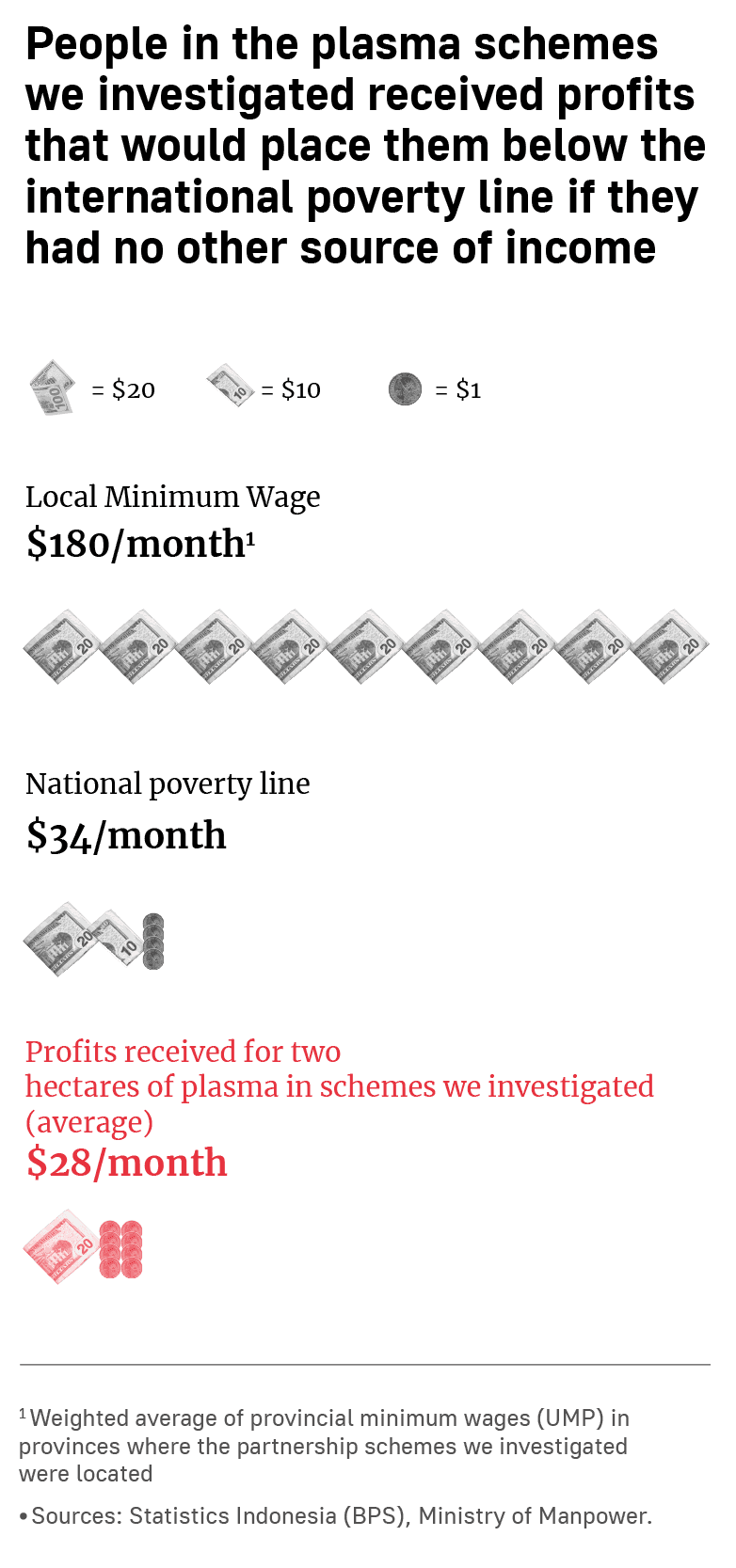

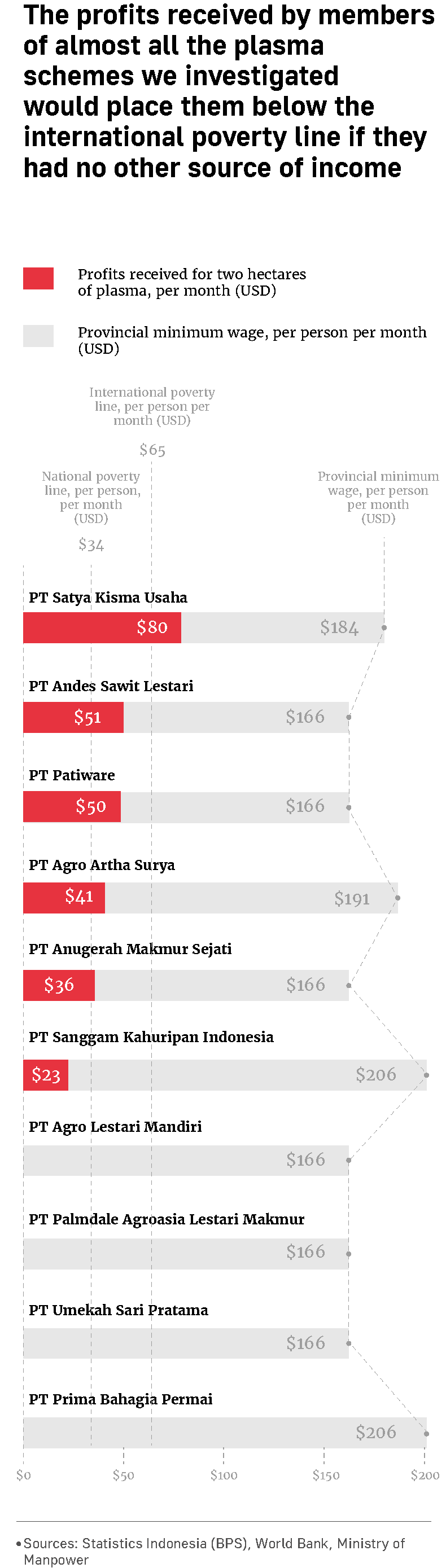

2. Meagre profits could leave villagers in poverty

If people in these schemes had no other source of income, the profits from plasma would place them below the international poverty line. Tania Li, an academic who has extensively studied plasma schemes, said this could be a “catastrophe”.

“It’s a terrible deal,” she said. “If you're somebody whose land has now been swallowed up by a corporation, and this dividend is all you have to live on, it matters hugely whether that amount is sufficient, and how it compares to what you would have had from an actual smallholding.”

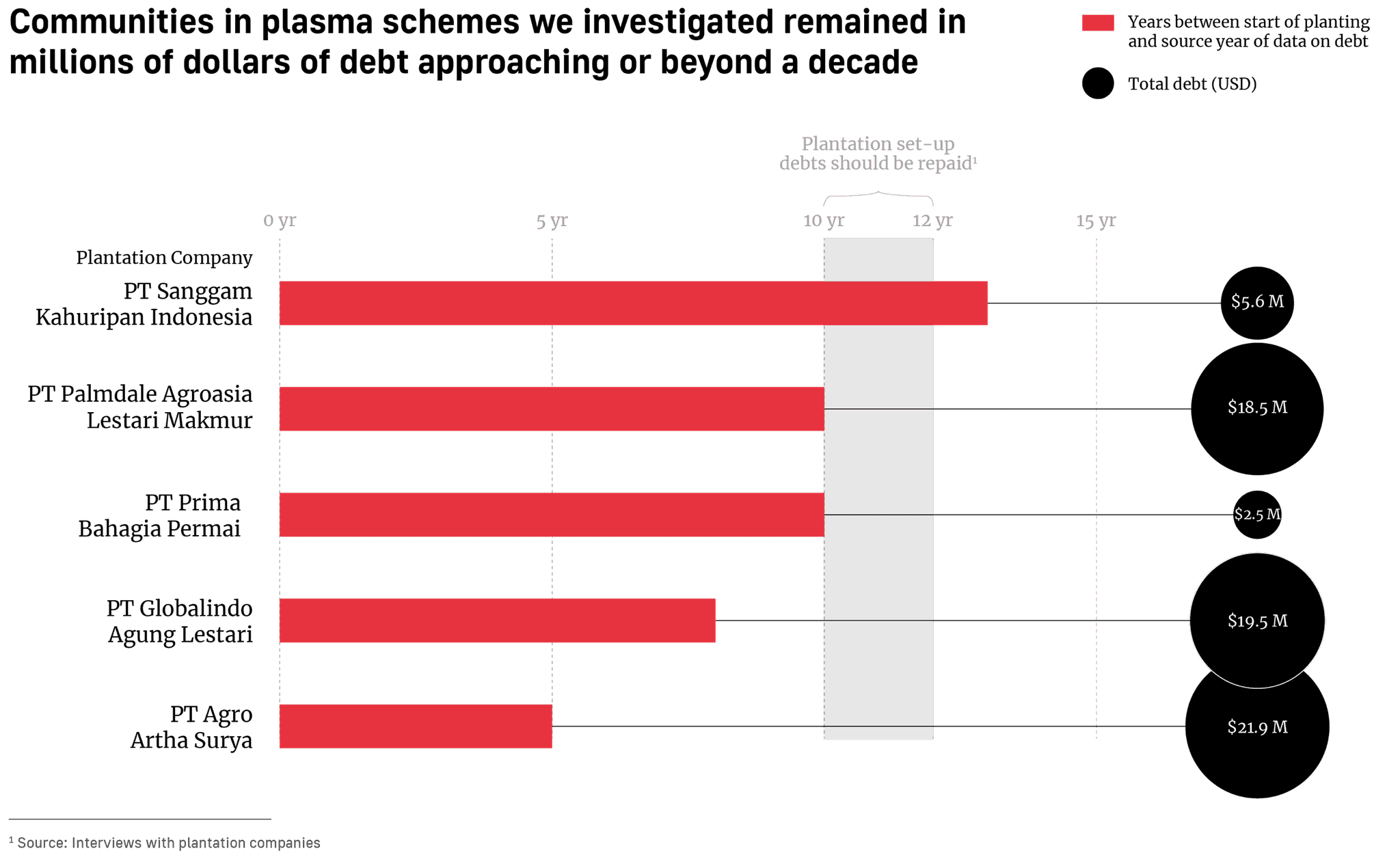

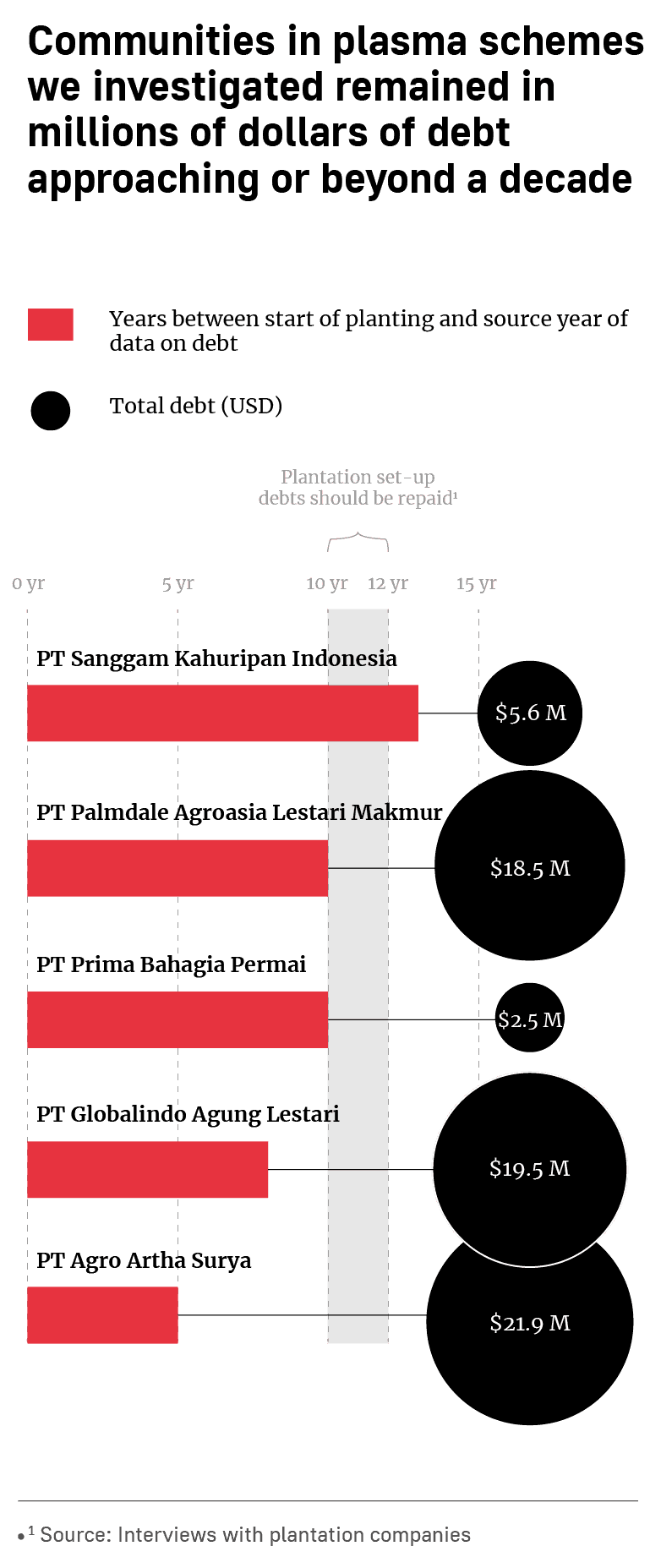

3. Communities are struggling to pay off vast debts

To join a plasma scheme, villagers were not only required to give up their land. They also had to take on substantial debts to finance the set-up costs of their plantations. With each villager afforded two or more hectares, and several hundred folded into each scheme, communities could collectively incur debts stretching into millions of dollars.

They then became reliant on companies managing their land properly to pay down those debts and see a profit. Companies told us these debts should be cleared after 10 to 12 years. But in some of the schemes we investigated, villagers still owed millions of dollars at or past this point.

4. Plasma schemes tied villagers into multi-decade contracts that experts say lack transparency and stack the odds against them

Plasma schemes required villagers — collectively represented by a cooperative — to enter into contracts with companies, to form a legal partnership. We obtained five such contracts and found that they provided companies extensive control over the land and finances of communities for several decades.

Experts who reviewed the contracts noted that they lacked transparency and were weighted heavily in favour of companies. Peter Batt, an agribusiness consultant who has analysed similar contracts for the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, described them as "grossly unfair". “These contracts are very, very much in the favour of the company," he said.

5. Villagers struggled to get explanations from companies

Many people we interviewed struggled to find out why their plasma schemes were not more profitable. In several cases they could not access basic information about the schemes they were locked into, from the extent of their debts to the location of their plasma plots. Some of the companies we investigated presented a different view, insisting they operated transparently and consistently shared information with the cooperatives.

6. Companies can suppress profits to their own advantage

Villagers, activists, academics and government officials all identified ways companies could manage plasma that would benefit them at the expense of communities. This included placing plasma in less fertile soils or remote areas. In one case, villagers were able to photograph the plantation using a drone, revealing that their plasma was largely barren while the company’s portion was better kept.

A plantation agency official noted that if the plasma was not managed properly, “the result is an increase in debt, not income,” for villagers.

The contracts we reviewed gave companies the right to calculate the overheads of managing the plasma and deduct it from villagers’ revenues. This included labour costs, fertilisers, and management fees. A damning 2020 report by the Indonesian government’s anti-monopoly agency, known as the KPPU, found that plasma schemes made an insignificant contribution to farmers’ incomes because of the “large number of cuts” companies applied to their revenues.

7. Some partnership schemes may be illegal

The KPPU has also been investigating plasma schemes on the grounds that they may violate a 2008 law that prohibits companies from “controlling” smaller entities in partnerships. According to a legal expert who gave evidence at a KPPU hearing in 2022, a company is likely to be legally “controlling” a plasma cooperative if, among other things, the cooperative has no access to information about the plasma’s location or development costs — phenomena that were present in several of the cases we investigated. The KPPU has investigated more than 20 cases in recent years.

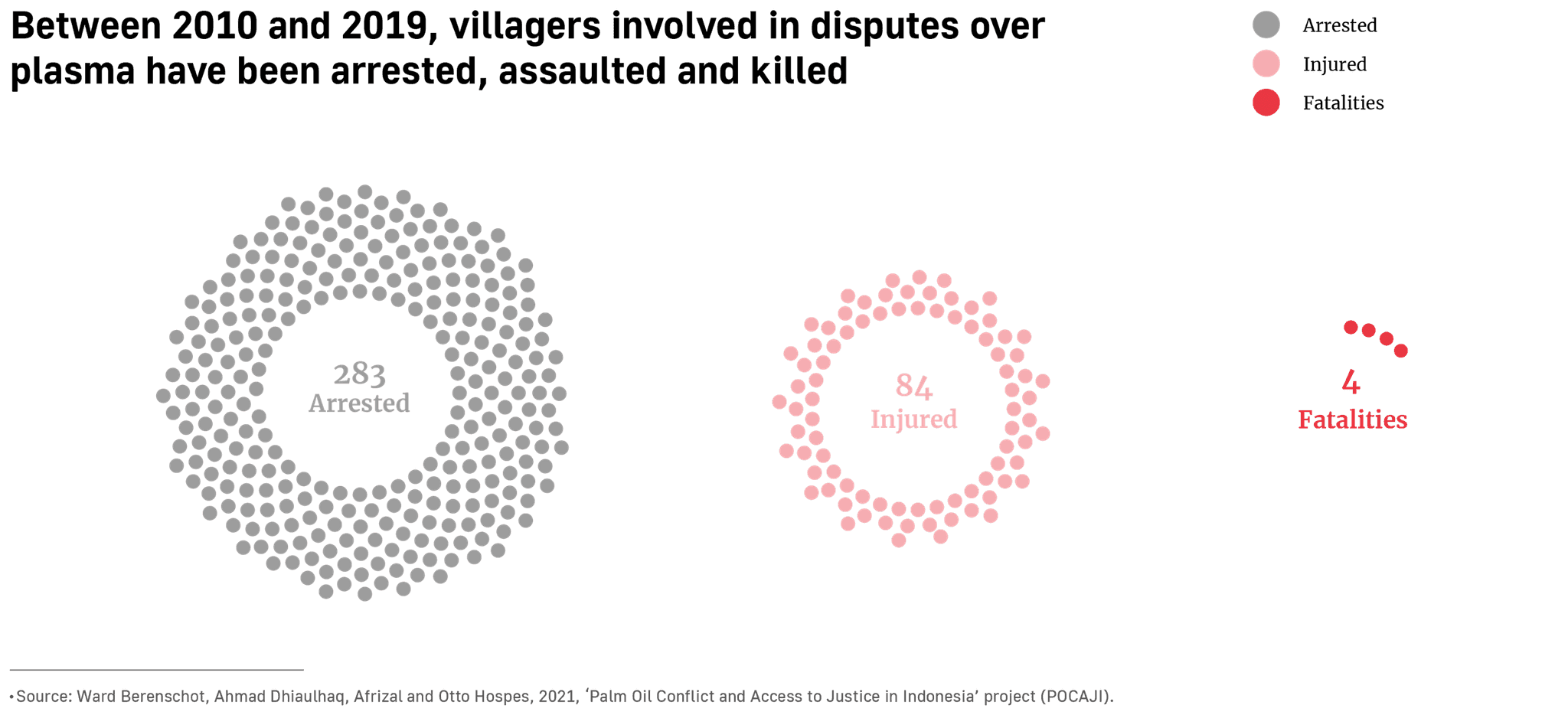

8. Without other recourse, villagers have turned to protests and direct action, but have been persecuted and criminalised as a result

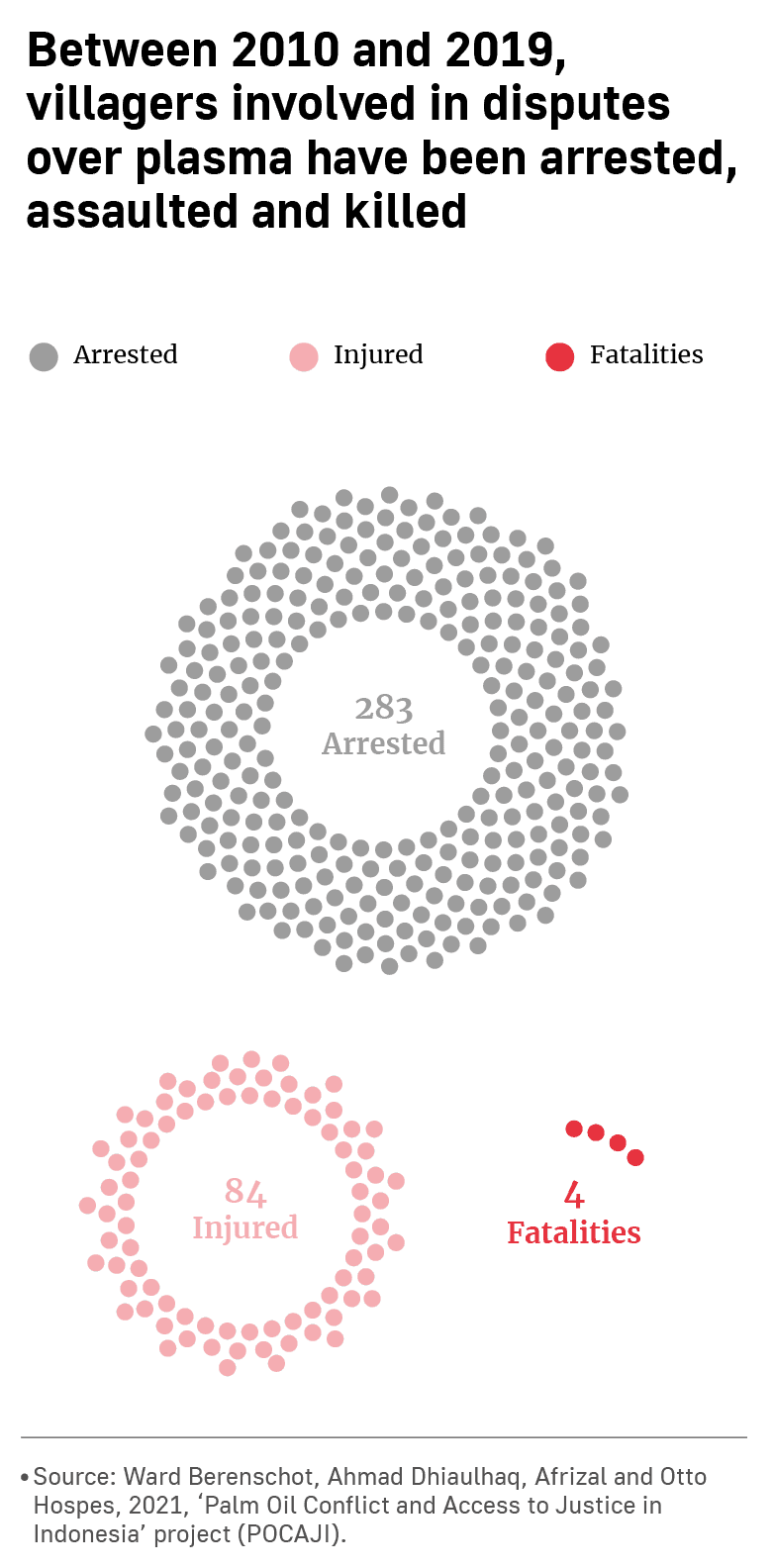

With communities struggling to compel companies to operate transparently — let alone share more profits — many have turned to protest. A recent academic study examining 150 conflicts between communities and palm oil firms found grievances over plasma in 57 percent of the cases. In three quarters of these, villagers had carried out demonstrations. But they faced arrest and even violence when doing so.

In one case we investigated, a villager named Herkulanus Roby took part in a peaceful protest after his community discovered their debt had swelled by more than $3 million. He was arrested and sentenced to a ten-month prison term. More than a decade after giving up his land, he is still waiting for it to generate any profits.

9. An ongoing government audit is examining problems with plasma

Earlier this year the Indonesian government announced an audit of the palm oil industry to address a litany of concerns, including widespread allegations of problems with plasma. Statements by public officials indicate the audit has focused on companies failing to provide plasma - as revealed in an earlier exposé by The Gecko Project. But it is also assessing the problems identified in our latest investigation.

At a parliamentary hearing in the district of West Kutai, in September, legislators said they had asked auditors to investigate cases in their jurisdiction, after discovering communities were facing “enormous” debts and little profit. “If [they] find indications of violations, especially crimes, it is clear they should be prosecuted,” said Ridwai, who leads a committee focusing on the palm oil industry in the district.

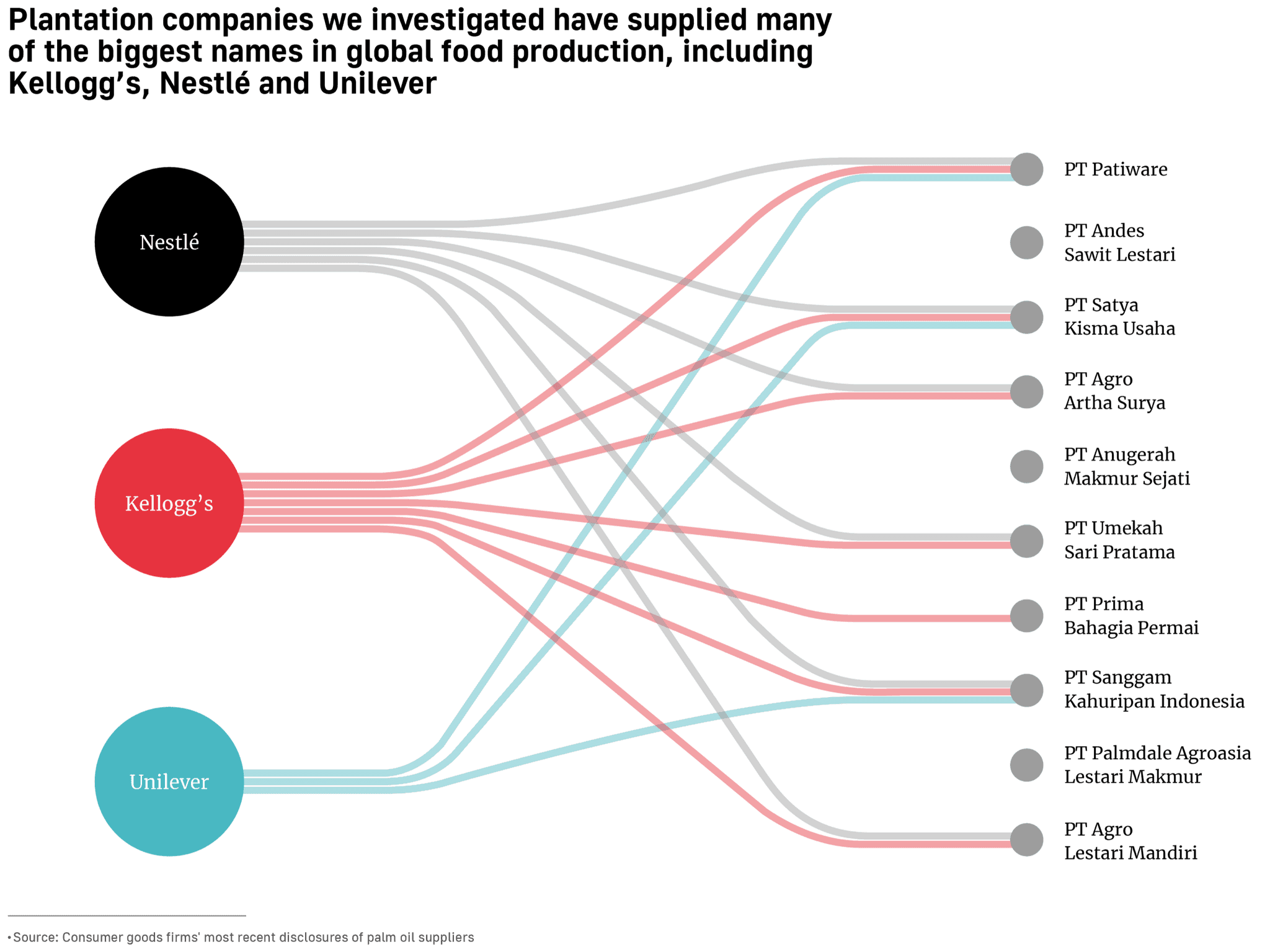

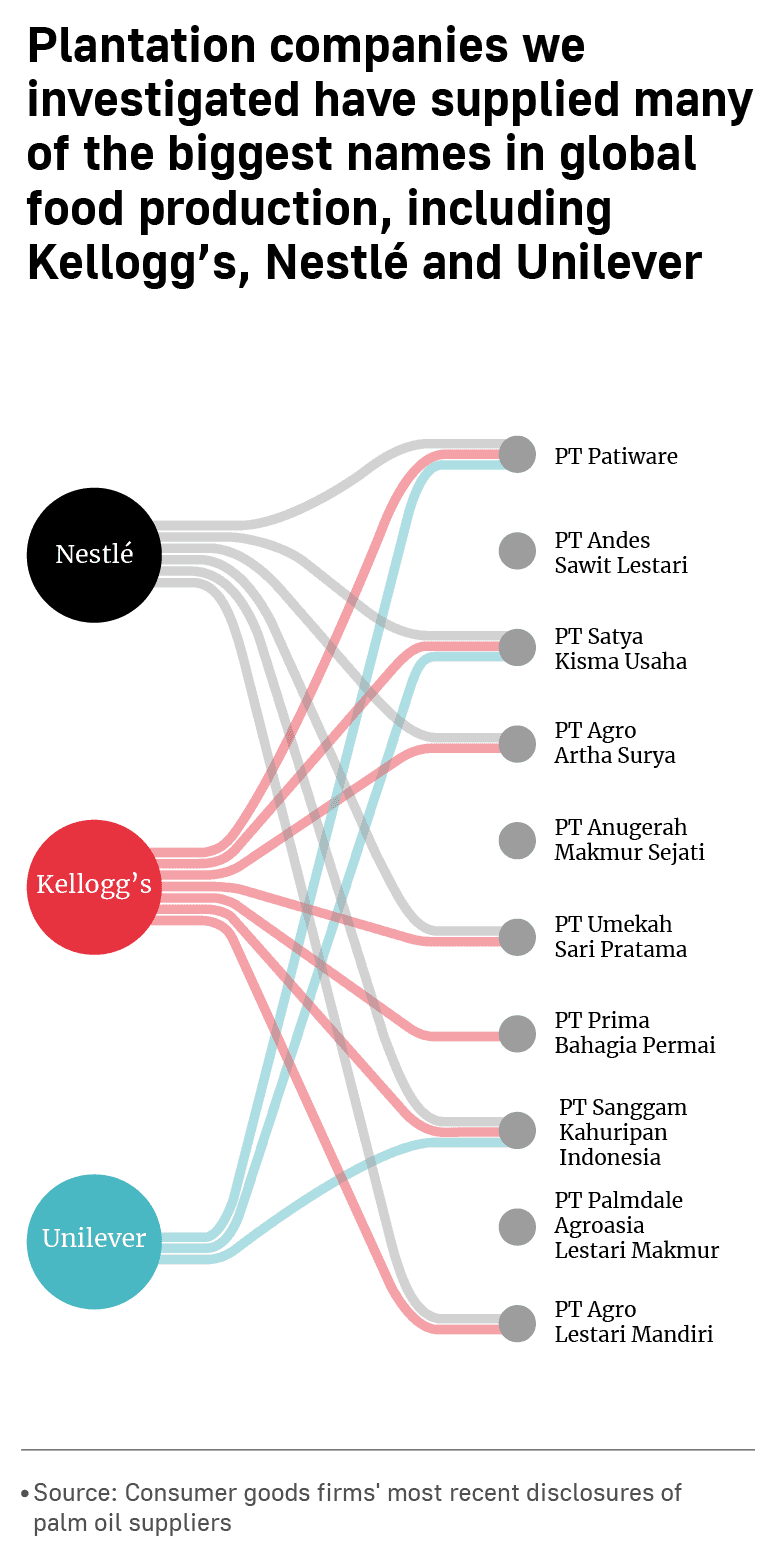

10. Major brands are hoovering up palm oil from plantations where communities have been exploited

We examined public disclosures by three major consumer goods firms, to find out if they were sourcing palm oil from the companies we investigated. The companies — Nestlé, Unilever and Kellogg’s — were all buying from plantations where villagers are making little or nothing from their plasma schemes. All three companies told us they were discussing the issue with their suppliers.

“Large buyer companies of crude palm oil and certified sustainable palm oil have gotten away with too much for too long,” said Piers Gillespie, who spent 16 months studying plasma schemes in Borneo as part of doctoral research. “Because, like it or not, it is absolutely part of their procurement and ESG responsibility to provide more support, training and governance to improve livelihoods and create better outcomes for smallholders.”

“They should be doing a hell of a lot more — and not seek to look the other way or avoid the challenges that the sector’s growth and their demand for the product has created.”

Read more

Read the full, in-depth investigation or read it in PDF format (5MB).