Earlier this week, The Gecko Project, BBC News and Mongabay released a joint investigation into a scheme that was intended to help lift millions of Indonesians out of poverty and cut them in on the spoils of the global palm oil boom, but has instead been plagued by allegations of exploitation and illegality.

Indonesia produces millions of tons of palm oil each year, much of it destined for supermarket shelves in Europe and the U.S., where it goes into everything from frozen pizza to laundry detergent.

When the industry began to take off in Indonesia in the 1980s, communities were supposed to benefit by getting a share of large-scale plantations, a portion known as “plasma.” Initially the government encouraged and incentivised this through policies, and it became routine for companies to promise villagers a share of their plantation, sometimes as much as 80 per cent. From 2007, it became a legal requirement for companies to share a fifth of any new plantation with communities.

In our field reporting on the palm oil industry in recent years, from Sumatra to Sulawesi, we frequently came across allegations that companies had failed to meet both promises and legal obligations. But there had been no systematic attempt to find out how big this problem was, or what impact it was having on communities. We set out to fill that void.

Here are six takeaways from the investigation:

1. Communities are likely being deprived of hundreds of millions of dollars every year

Our analysis of government data suggests companies have failed to provide hundreds of thousands of hectares of legally required plasma to Indonesian communities, costing them hundreds of millions of dollars each year in lost profits. In Central Kalimantan province alone, we estimated, villagers are collectively losing more than $90 million each year.

2. Disputes over plasma pervade the industry and have become a major source of unrest

Over the past decade, at least 155 palm oil companies have been accused of failing to provide plasma, according to a database we compiled of local media articles, academic papers, NGO reports, and other publicly available sources. These include subsidiaries of almost every major palm oil conglomerate operating in the Southeast Asian country.

As a result, dozens if not hundreds of rural communities have turned to protest or other forms of direct action, marching in the streets, massing outside government offices, blockading roads and occupying plantations. These incidents have taken place at a rate of more than one a month over the past five years. Many villagers involved in such actions have faced violence at the hands of police or been sentenced to prison time.

3. Government intervention in plasma disputes has been limited and mostly ineffective

Regional government approaches to resolving plasma disputes have tended toward informal mediation between companies and communities, but research suggests this typically fails, a conclusion backed by our investigation.

While public officials sometimes threaten punitive action against companies over plasma disputes, very rarely do they follow through, we found, allowing conflicts to fester for years or even decades.

4. An audit by Jakarta appears to have made little progress on plasma

In 2018, President Joko Widodo launched a national audit of the palm oil industry. Among other things, it was supposed to check whether companies were complying with plasma regulations and, where necessary, “accelerate” the provision of smallholdings. Four years on, however, the administration appears to have made little progress, and it remains unclear whether the review has led to any action on plasma.

“We are still collecting comprehensive information” on plasma, Surya Tjandra, deputy minister at the National Land Agency, which is coordinating the audit, told us. “There really isn’t much.”

5. Indonesia’s largest palm oil producer has failed to provide legally required plasma in several plantations

While Golden Agri-Resources has stated publicly that almost 21% of its total planted area is plasma, the reality is more complex.

The conglomerate’s plasma, we found, is disproportionately concentrated in just five of its 54 subsidiaries. These are older plantations dating back to the 1990s and early 2000s, when it was not uncommon for companies to allocate 70% of their plantations as plasma.

Golden Agri has acknowledged publicly or in response to our questions that it has yet to provide all of the plasma required by law in eight subsidiaries. Even where it has provided plasma, we found, some communities have had to wait well over a decade for the smallholdings to materialise. In response to our findings, the company said it is committed to complying with plasma regulations and this is a “work in progress.”

6. Palm oil tainted by plasma disputes is flowing into the supply chains of major brands

While many of the world’s largest consumer goods firms have promised to root out deforestation, land grabbing, labour abuses and “exploitation” from their palm oil supply chains, they appear to have a blind spot when it comes to plasma.

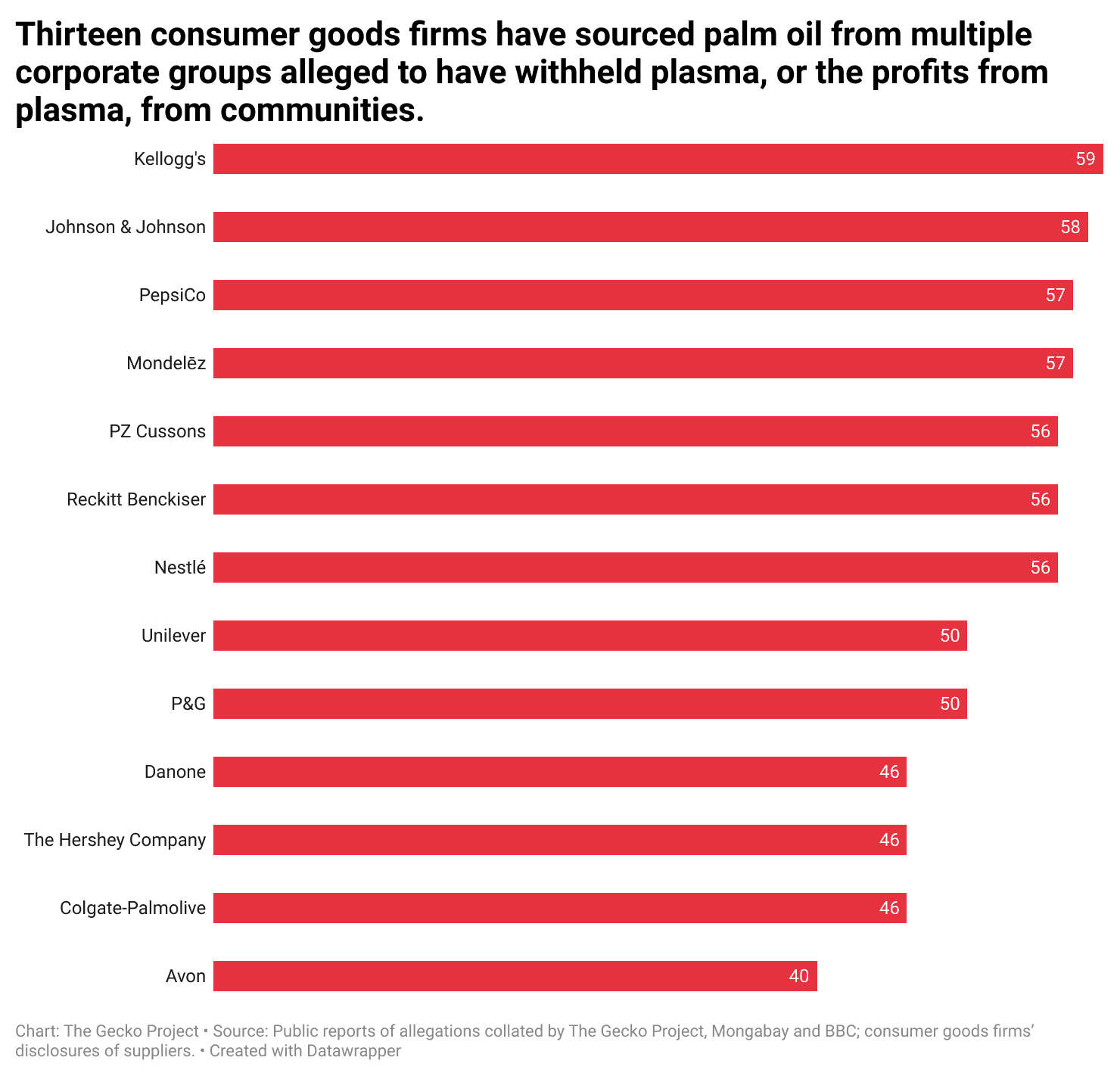

We found that more than a dozen such companies, including Nestlé, Kellogg’s, Unilever, Johnson & Johnson, and PepsiCo, have sourced palm oil from producers alleged to have withheld plasma, or the profits from plasma, from Indonesian communities over the past eight years.

All of these companies have sourced palm oil — according to their most recent disclosures — from a Golden Agri plantation that has failed to provide plasma for more than 13 years, despite being required to as a condition of its license.

In response to a summary of our findings, the buyers pointed to their existing policies aimed at protecting human rights and eliminating "exploitation" from their supply chains.

Some noted that they required their suppliers to comply with the law. They said they engage with their suppliers when potential violations of these policies are brought to their attention, and would do so for the cases identified in our article.

For a complete list of their responses, visit this page.