- Indonesia’s plasma scheme was designed to cut villagers in on the profits from the palm oil boom. But a decade after giving up their land, some are earning less than a dollar a day and still paying off vast debts.

- As plantations rapidly expanded, communities were tied into opaque, decades-long contracts that gave companies expansive control over their land and finances.

- Some of these contracts may be illegal, according to a leading government watchdog, which has investigated at least 20 cases.

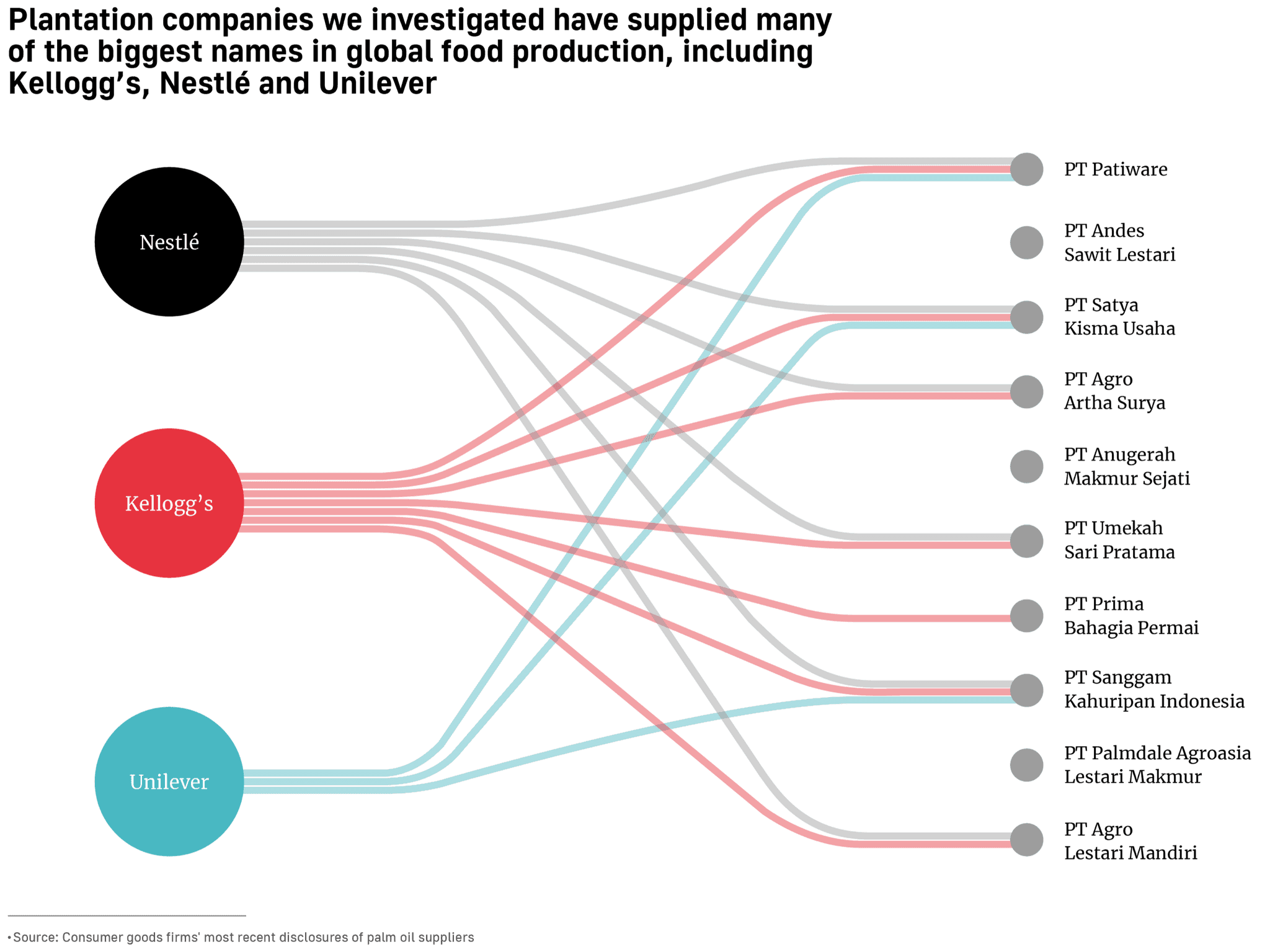

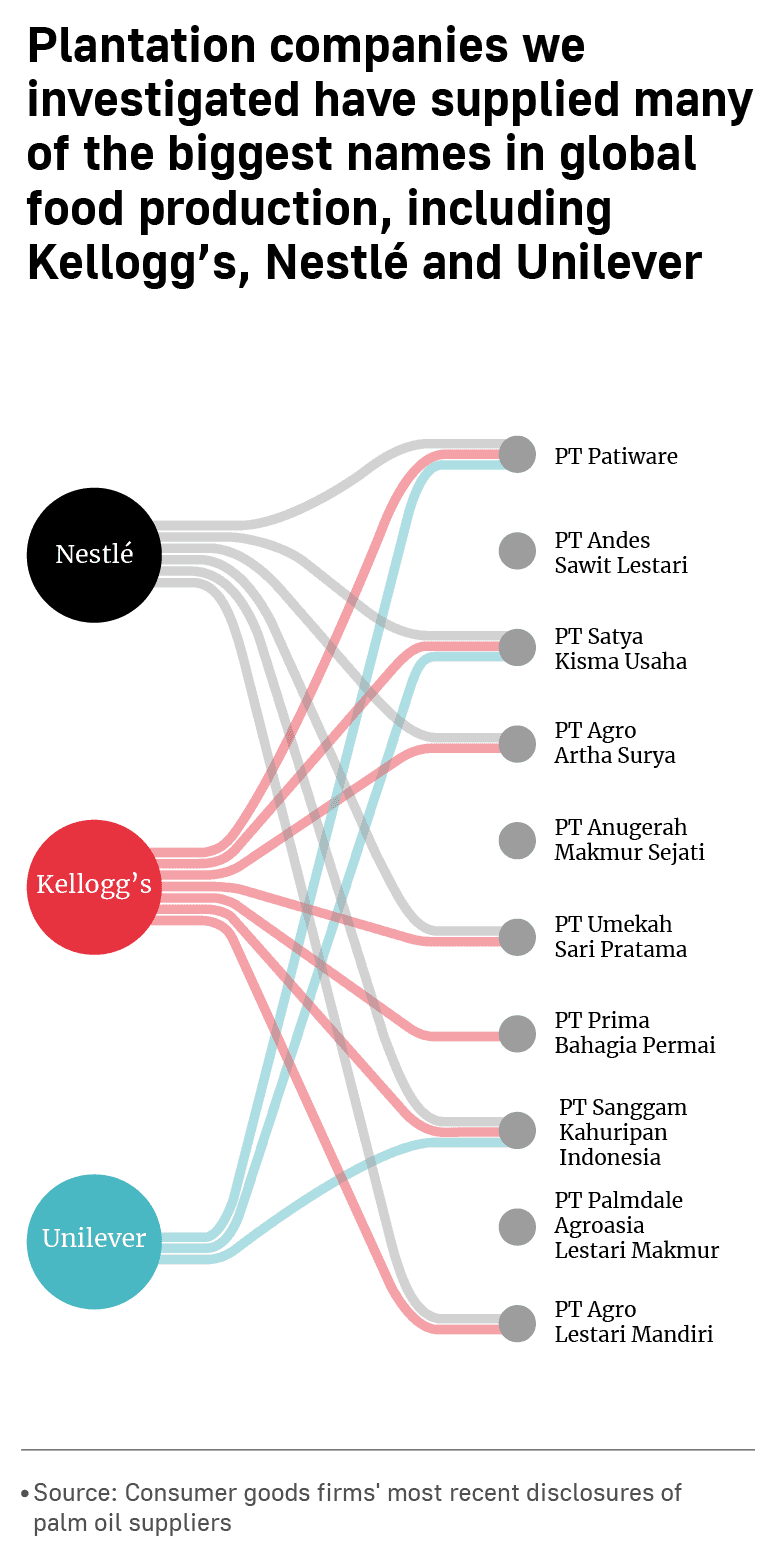

- Palm oil from plantations where communities are trapped in exploitative schemes is flowing into the supply chains of firms like Nestlé, Unilever and Kellogg’s.

This article is the product of a collaborative investigation between The Gecko Project, Mongabay and BBC News. Read a PDF version (5MB) here

Sit back, do nothing and watch the money roll in.

That was the promise made to villagers across Indonesia as they were asked to give up control of their land to corporations in exchange for a share in the profits from oil palm plantations.

But for some communities, it was little more than a mirage. More than a decade later they are earning less than a dollar a day — and find themselves submerged in millions of dollars of debt.

“We don't eat bones any more, we eat water,” said Rifai, a villager from the island of Sumatra. “Everything goes to the company.”

Since the 1970s, palm oil has offered communities in Indonesia a route out of poverty. As global demand grew for the commodity — to produce a dizzying array of products, from soap to chocolate to biofuels — plantations sprung up across the country. The nation became the world’s largest producer, sending millions of tonnes each year to Europe and the US and generating billions of dollars in profits.

The Indonesian government sought to ensure villagers would benefit by encouraging companies to give them a slice of their plantations. In the early years, they were handed a physical plot of land to tend - known as “plasma”. They harvested fruit and sold it to corporate-run mills, the first step in a supply chain that stretched from tropical islands to supermarket shelves.

In the mid-2000s, as the industry experienced its most rapid phase of growth, it became a legal requirement for privately-owned firms to provide a fifth of their plantations as plasma. But at the same time a new model became dominant. Instead of providing communities with their own plots, the corporations would manage the entire plantation and pay them the profits from their portion.

Under this system, villagers formed cooperatives that set up legal “partnerships” with plantation firms. In theory, the system offered them the opportunity to benefit from the technical expertise of the private sector. But it also turned them from farmers who cultivated their own land, to passive, minor partners in large plantations operated by corporations.

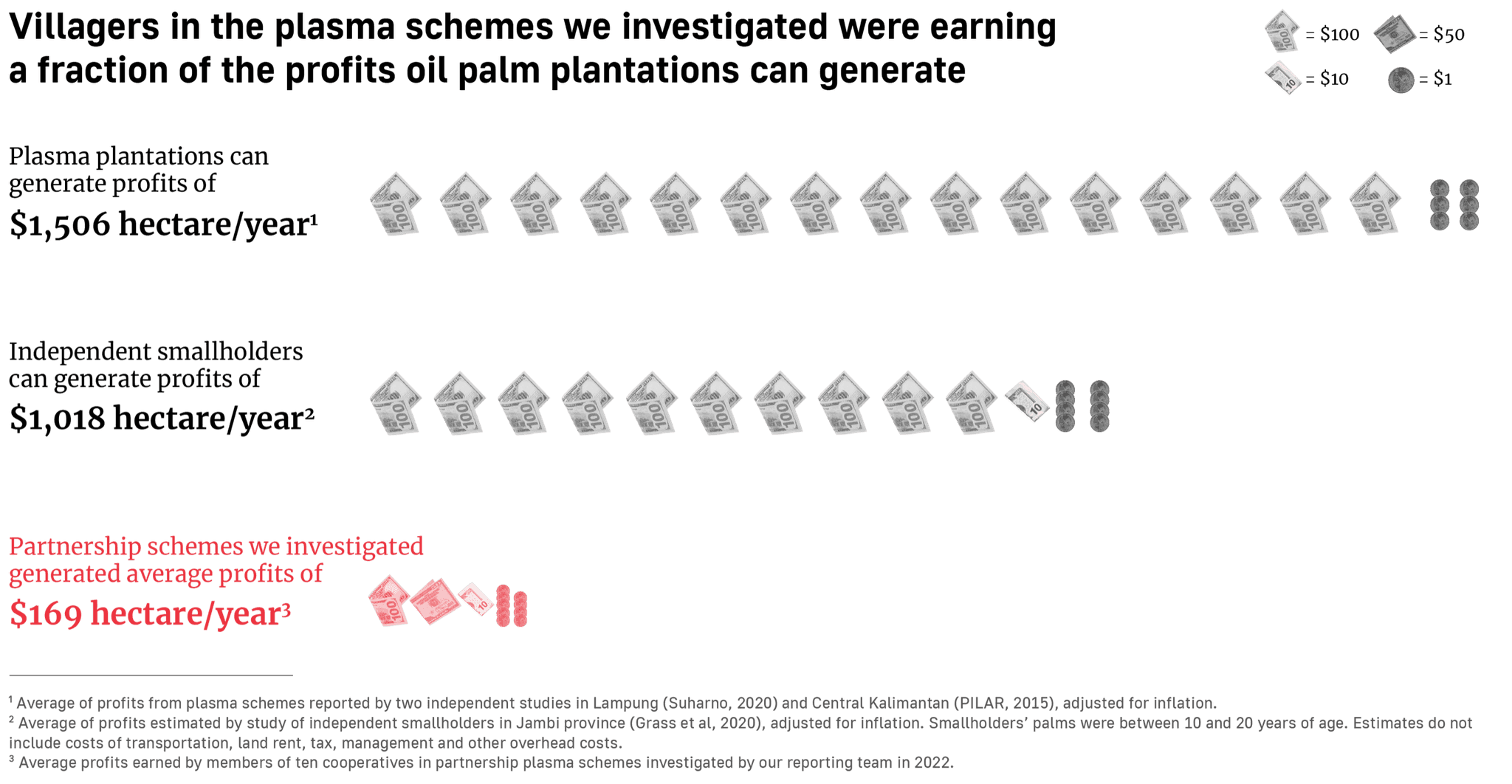

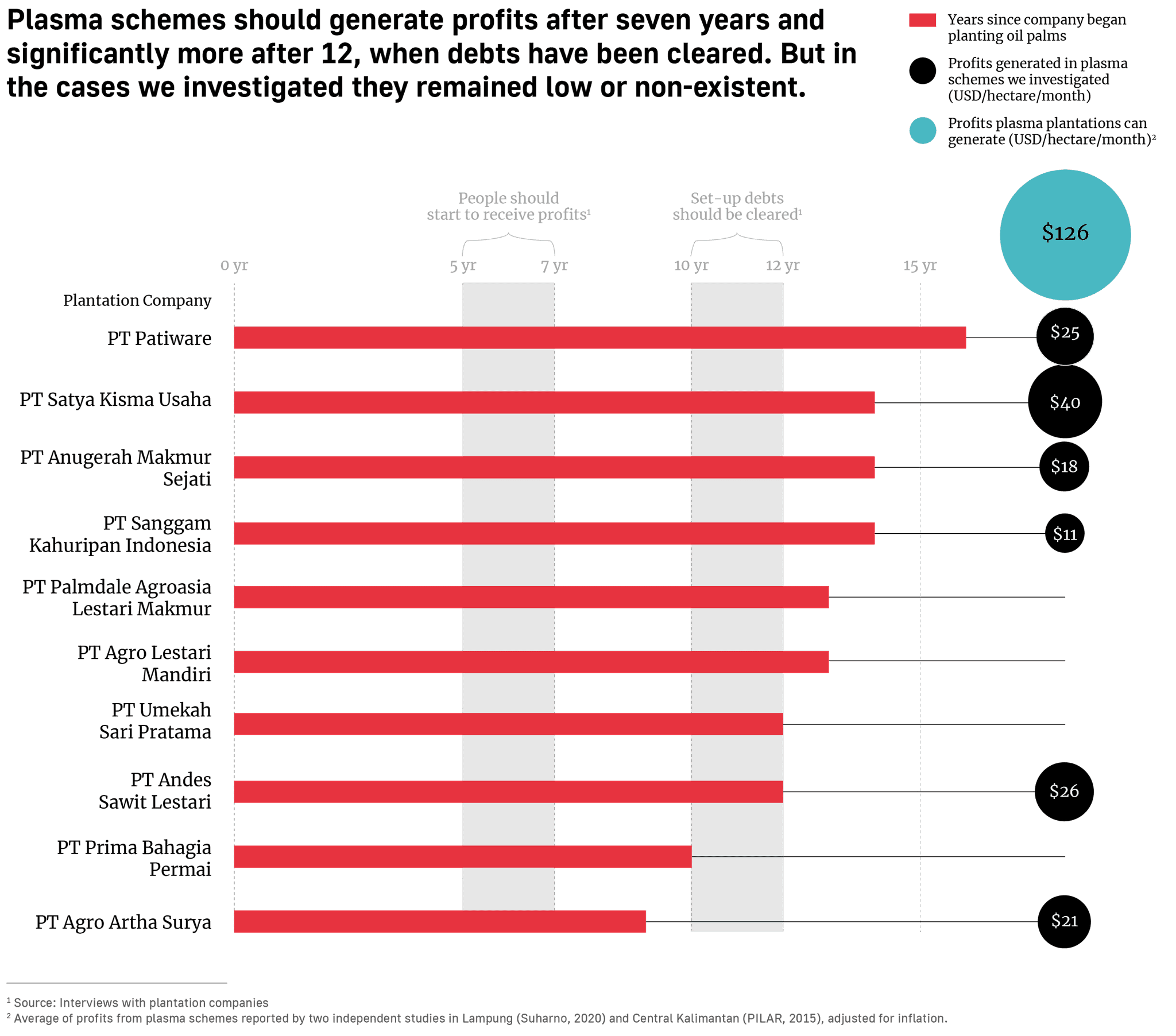

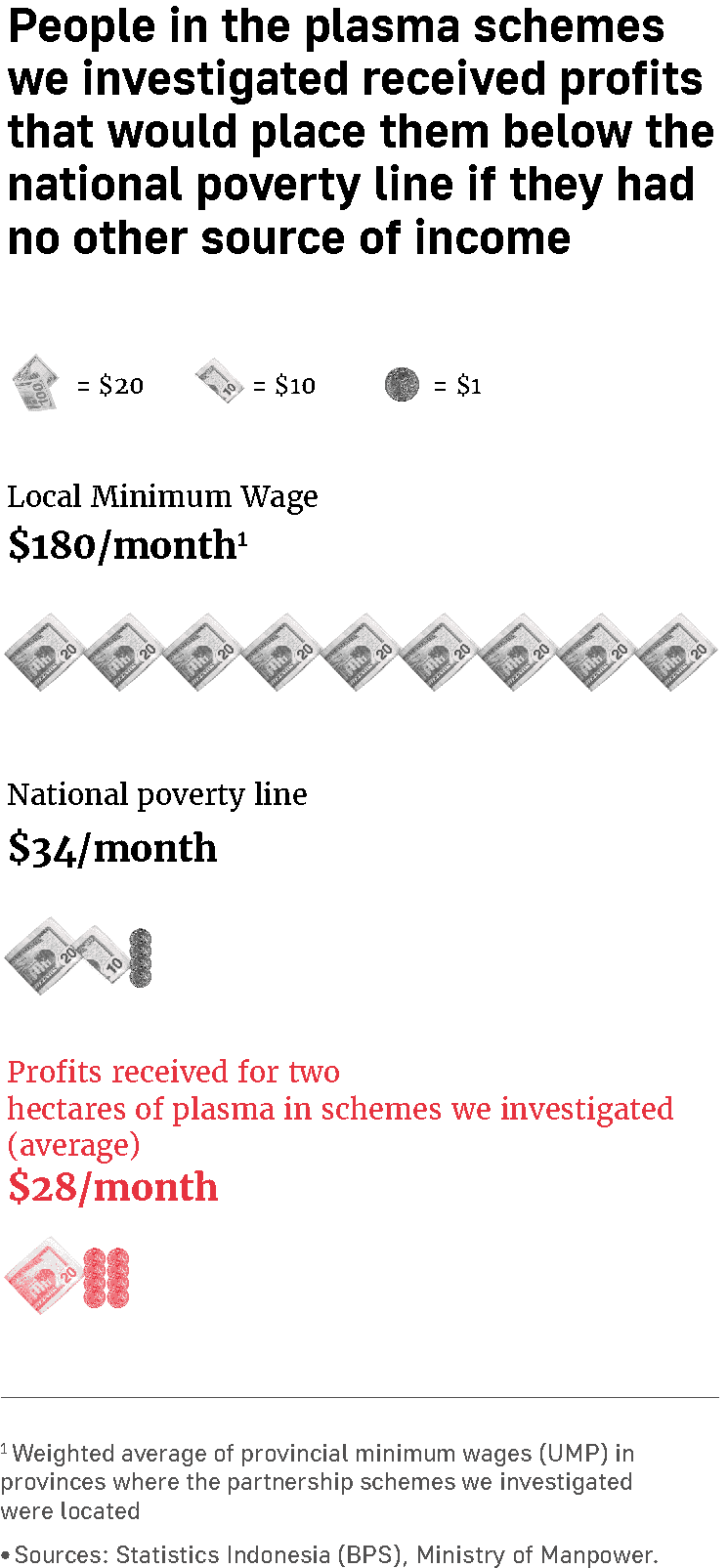

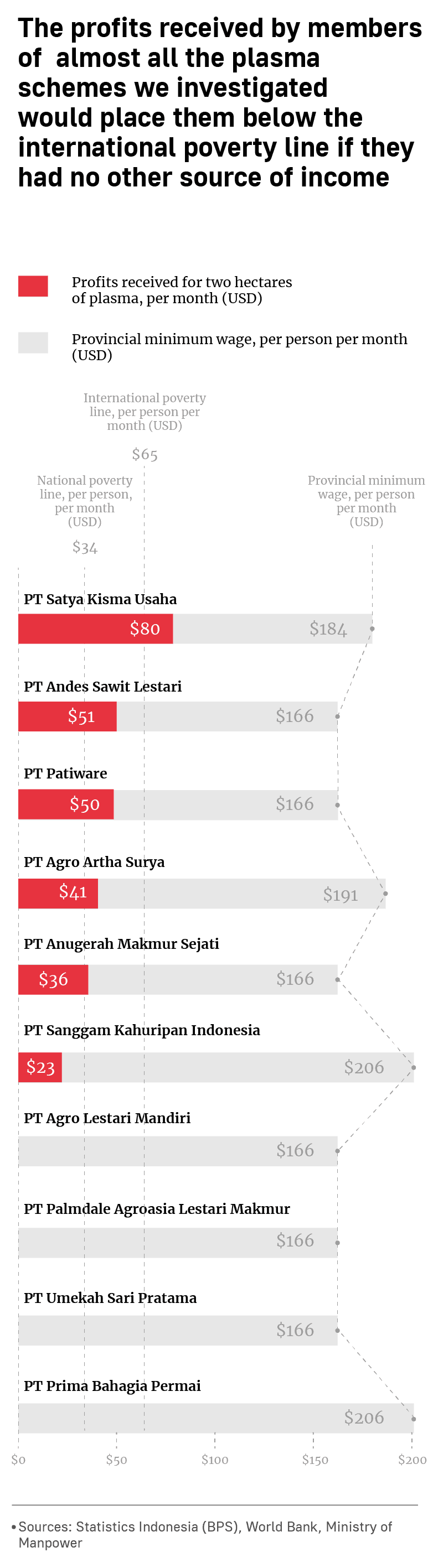

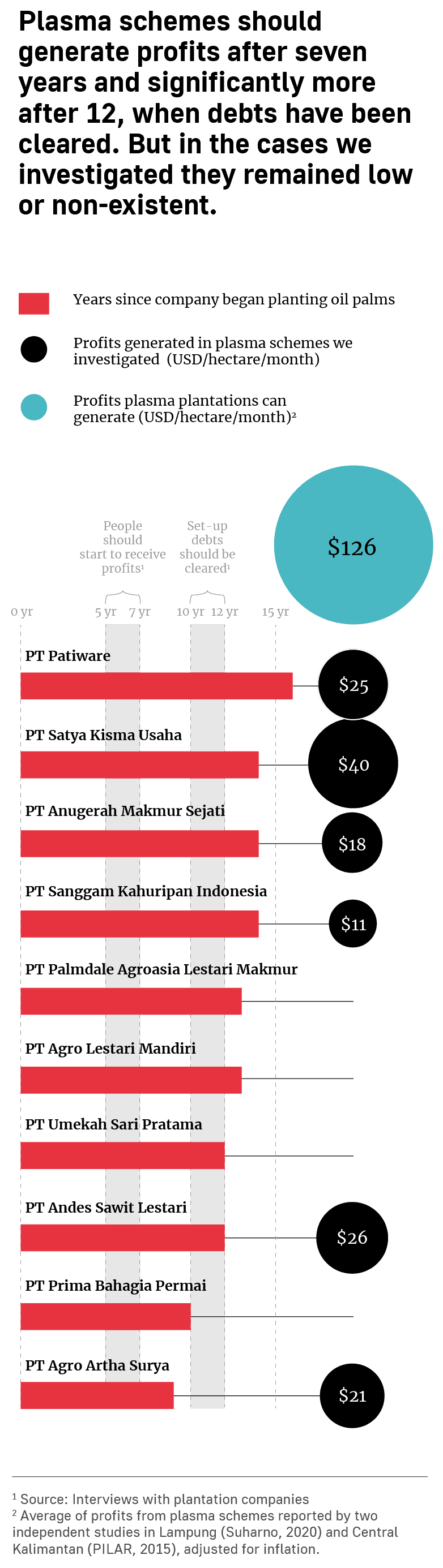

The Gecko Project — together with Mongabay and BBC News — obtained data on the profits received by communities in ten partnerships set up by oil palm firms, collectively involving more than 4,000 people. While plasma plantations can generate profits of more than $1,500 a year for a hectare of land, according to independent studies, in these cases villagers were earning around a tenth of that.

Seduced by the prospect of plantations that could bring economic development to remote villages, they were instead being paid less than a dollar a day, a fraction of the minimum wage and below the international poverty line.

Some were earning nothing at all, years after the plantations should have become profitable.

“What’s surprising is that we didn’t get anything. Not even one rupiah from that company in ten years,” said Martinus, a farmer from West Kalimantan. He had resorted to borrowing money from family members to fund his son’s education, after waiting in vain for the palm oil firm to pay him any profits. “They deceived us,” he said.

Our dive into this model began as part of a broader collaborative investigation examining problems with the Indonesian plasma system. In May we revealed that many companies were failing to provide plasma required by law, depriving communities of potentially hundreds of millions of dollars each year.

But in the course of the investigation, we also frequently encountered allegations that even where the plasma apparently did exist, communities were earning little or even nothing. Our analysis of reports from the Indonesian media, activist groups and academics turned up more than 70 cases in which such allegations had been levelled in recent years.

To understand why, we sent reporters to interview communities that had entered into partnerships with 12 palm oil firms, including subsidiaries of two of the world’s biggest agribusinesses. We reviewed court records, contracts, corporate and government data, and interviewed dozens of government officials and experts who have carried out extensive research on agricultural development in the global south.

Our investigation found that communities were signing contracts that gave private companies extensive control over their land and finances for three or more decades. This included giving companies the rights to manage multi-million-dollar loans, used to finance the set-up costs of the plantations.

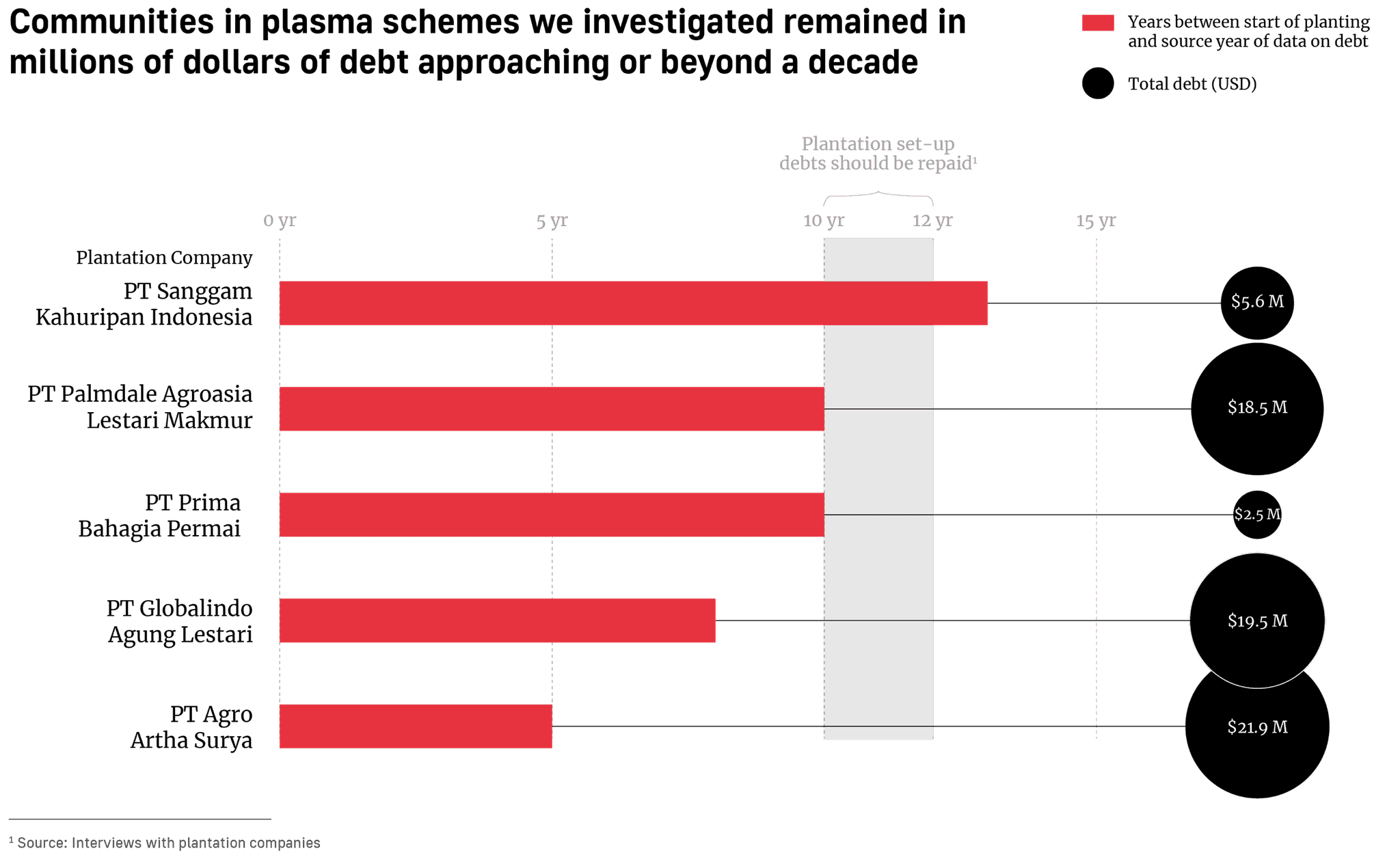

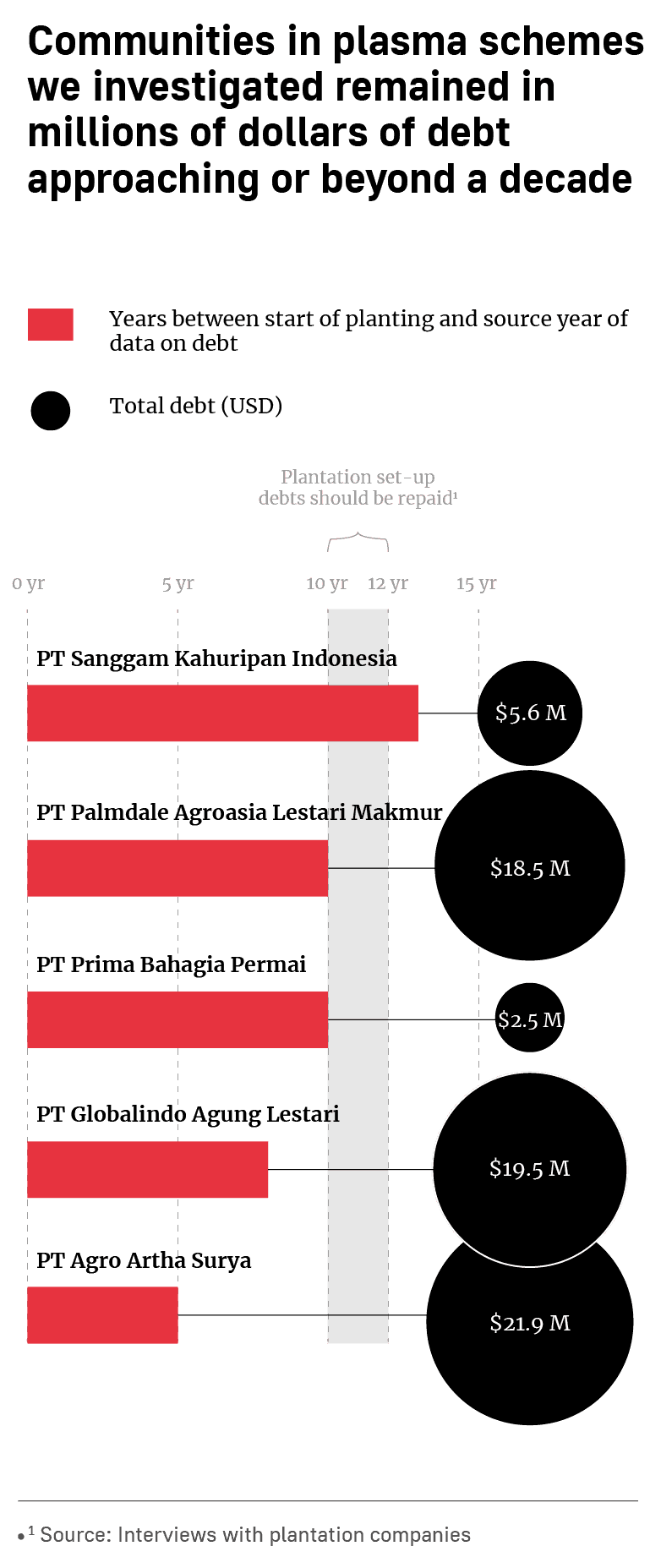

To pay down those debts, and eventually see a profit, the communities were reliant on companies developing and maintaining the plantation properly. But communities we visited had debts ranging from $2.5 million to $18.5 million, a decade after the plantations were established.

With debts accruing interest at an annual rate of 10 percent or more, some villagers questioned whether they would ever pay them off, let alone receive a profit.

“Before this plantation came, we had never been indebted to anyone for anything,” Siana, a mother of three from Kapuas Hulu, on the island of Borneo, told a researcher studying plasma schemes. “Every time I receive the debt letter from the bank, I think to myself, ‘We are doomed’. Imagine receiving a letter of debt when you never see the money.”

Many of the people we interviewed struggled to determine why they were receiving limited or no profits. In case after case, people who had signed up to partnerships said they were unable to access basic information — from the status of their loans to the location of their portion of the plantation — that would enable them to hold companies to account.

Experts who reviewed five contracts that tied villagers into these partnerships commented that they lacked transparency and stacked the odds against communities. Peter Batt, an agribusiness consultant who has analysed similar contracts for the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, described them as "grossly unfair".

“These contracts are very, very much in the favour of the company," he added.

In response to our questions, the plantation companies we investigated insisted that they operated fairly, transparently and within the law. But our investigation found companies can exploit the opacity in partnership schemes to manage plantations in ways that benefit them at the expense of villagers. We encountered repeated allegations that companies were doing so in the cases we examined.

A damning 2020 report by the Indonesian government’s anti-monopoly agency, known as the KPPU, found that plasma partnerships had created “financial efficiency” for companies, while piling debts onto villagers that suppressed their profits. It found that partnerships made an insignificant contribution to farmers’ incomes because of the “large number of cuts” companies applied to their revenues.

In the past four years the KPPU has investigated at least 20 plasma partnerships on the grounds they may be illegal, violating a 2008 law that prohibits companies from “controlling” smaller parties in partnerships, and is taking on a growing number of cases each year.

But Guntur Saragih, the deputy head of the agency, told us it had half the budget it needed to investigate the situation comprehensively. It is only able to examine a fraction of the partnerships that have proliferated across Indonesia in the past decade and a half, potentially locking hundreds of thousands of families into contracts that will last for a generation.

In the absence of an effective government solution, observers with a close understanding of the problems with the partnership system told us the global companies buying palm oil also need to act. Several major consumer goods firms have committed to supporting Indonesian smallholders, to ensure they are able to benefit from the trade in palm oil. But the companies we investigated have supplied many of the biggest names in global food production, including Kellogg’s, Nestlé and Unilever.

“Large buyer companies of crude palm oil and certified sustainable palm oil have gotten away with too much for too long,” said Piers Gillespie, who spent 16 months studying plasma schemes in Borneo as part of doctoral research. “Because, like it or not, it is absolutely part of their procurement and ESG responsibility to provide more support, training and governance to improve livelihoods and create better outcomes for smallholders.”

“They should be doing a hell of a lot more — and not seek to look the other way or avoid the challenges that the sector’s growth and their demand for the product has created.”

The promise was very convincing

When a plantation company arrived in the village of Teluk Bakung in the late 2000s, Maurus Rita Dihales, who goes by Rita, believed it would help his community.

Teluk Bakung is made up of a series of hamlets whose residents were subsistence farmers. They also generated cash income by harvesting rubber and working in plantations. Though it straddled the main road running across Indonesian Borneo and stood just an hour’s drive from the capital of West Kalimantan province, it remained under-developed. Large areas of the village had no access to mains electricity.

Then in his mid-30s, Rita believed it was a place in need of “serious investors”.

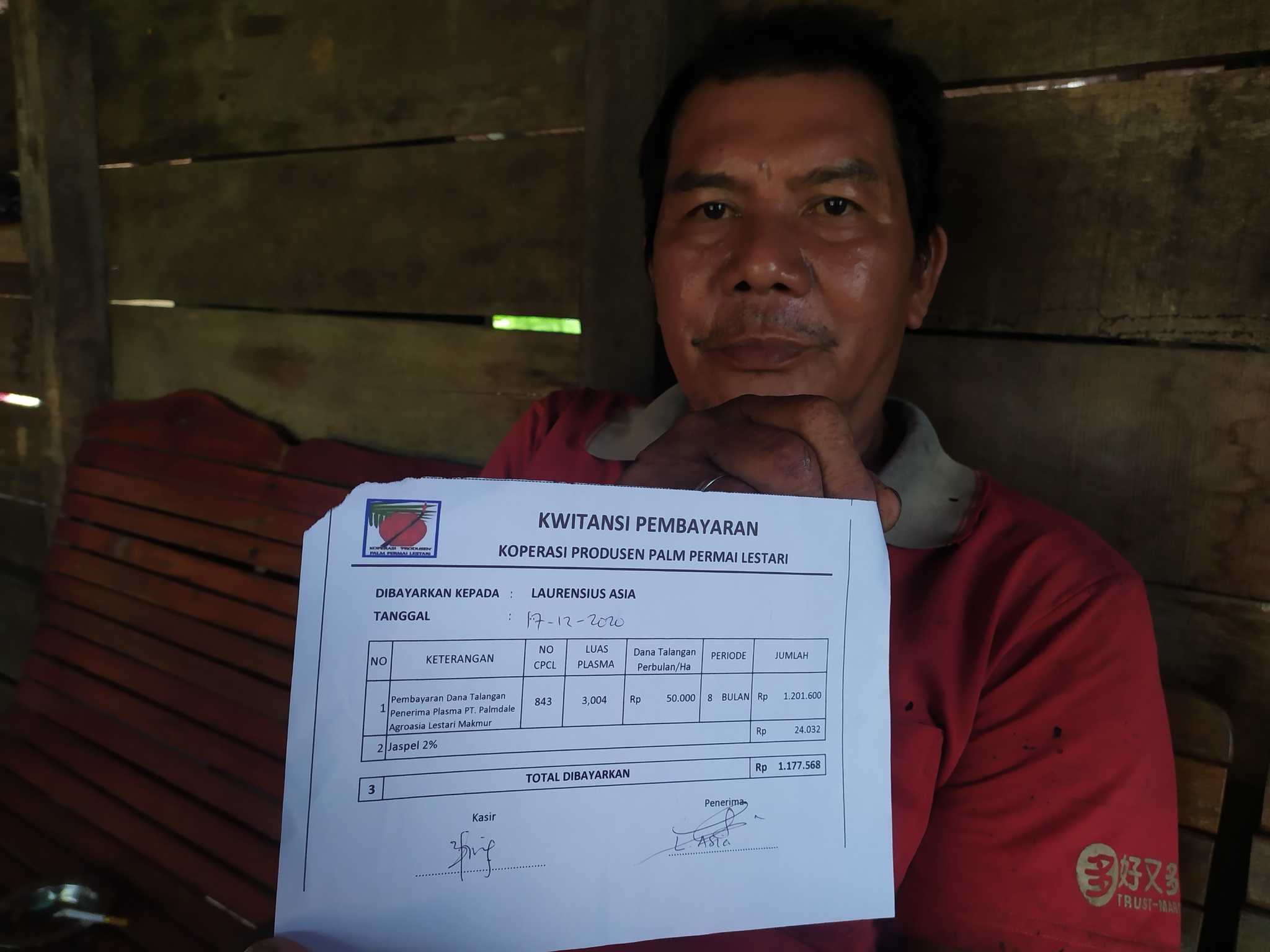

The company, PT Palmdale Agroasia Lestari Makmur, told Teluk Bakung’s residents it would bring jobs to the village and their own share of the oil palm plantation, in the form of plasma. Rita hoped to use profits from his share to fund the education of his two children.

“The promise was very convincing,” he told us more than a decade later. In February 2010, he signed a simple deal with Palmdale, giving the firm control of 72 hectares of land. Palmdale would profit from 70 percent of it, and Rita from the remaining 30 percent. In all, more than 900 people would join Palmdale’s plasma scheme.

By the late 2000s, plantation companies were fanning out rapidly across what would become Indonesia’s palm oil heartlands. As they sought to convince communities to give up their land, plasma was a key part of the pitch.

Marcus Colchester, an anthropologist and activist who has advocated for the rights of indigenous people in Indonesia for four decades, said companies would seek to convince villagers by showing them successful, older plasma projects on the island of Sumatra.

“This is very common — community leaders will be taken to Riau to be shown the scheme there,” he said. “‘Look how wealthy everybody is here. This is what you can look forward to in Kalimantan’. And they go back having had a lovely time in a hotel and they sign away the village land.”

Villagers we interviewed who received specific details of the potential financial benefits of partnership schemes were told they would receive between 1.3 million and 1.8 million rupiah a month for each hectare of plasma. This could equate to between $2,982 and $3,677 a year, for the average person with a two-hectare plot. Most did not remember specific figures, but recounted bold promises of “prosperity” or “big income”.

“If you’re going to get so many millions [of rupiah] every month into your bank accounts, and you don't have to do anything, it all sounds very attractive,” said Tania Li, an anthropology professor at the University of Toronto who has extensively studied Indonesian smallholders. “But it's a scam.”

Signing up to plasma partnerships came with a cost. The villagers were required to give up their land and get a fraction of it back — most would be used by the corporations for their own portion of the plantation.

Community representatives were also required to take out bank loans to finance the set-up costs, which could reach $4,000 per hectare or more. With each villager afforded two or more hectares, and several hundred folded into each scheme, villagers could collectively incur debts stretching into millions of dollars. Their land would be put up as collateral for the loans.

The precise terms of each plasma partnership were laid out in contracts struck between plantation firms and villagers, collectively represented by a cooperative. These contracts would govern the land and finances of entire villages for at least 25 years. But communities were provided with little or no support in the negotiations, according to government sources.

Officials from ten plantation agencies told us they took a broadly hands-off approach, in most cases, leaving villagers to agree to the contracts themselves. A 2014 government review found that negotiations pitted companies with a “legal department expert in making cooperation agreements” against villagers who had “generally” been educated to high school level and did not understand “the consequences or legal risks” of the deals they were entering into.

“The main risk in how plasma schemes are implemented is how these negotiations work out between a very unequal set of partners,” said John McCarthy, a professor at the Australian National University who has carried out extensive research on the Indonesian palm oil sector.

Five partnership contracts we analysed as part of our investigation required plasma cooperatives to take out a loan to finance the set-up costs of the plasma. In one case the loan would be “jointly managed”, but in the others the cooperatives transferred control of the money to companies. The companies then acquired broad discretion over how the loans were spent, with only one including formal checks by the cooperative.

Opacity begins with access to contracts

Plasma partnership contracts are rarely made public and often difficult to obtain. "In general, farmers do not have a copy of their contract," said the academic Zahari Zen, who has studied the palm oil sector for more than 15 years and advised the North Sumatra provincial government on the subject. Piers Gillespie, the researcher, found that the majority of the cooperatives he researched in West Kalimantan no longer had copies of the contracts they had entered into.

We were able to obtain contracts for only three of the 12 plasma partnership schemes we investigated. We obtained two contracts, from other sources, that were not among the schemes we visited. All five contracts were signed between 2010 and 2016. We shared these five contracts with seven experts on rural development in the global south, or the oil palm sector specifically, for comment.

By the time the trees were producing fruit, four of the five contracts also gave the companies outright authority to calculate the overheads of running the plantation and deduct them from the cooperatives’ revenues. That included the costs of fertiliser and harvesting and transporting fruit. But it also included a range of other cuts that would go straight to the company. One took a five percent cut of the loan taken out by the cooperative; another took five percent of any revenues even before it had made any profit.

“A lot of these terms give the company complete control,” said Darryl Vhugen, a lawyer and consultant on responsible investment who reviewed key clauses from the contracts we obtained.

Experts who reviewed the contracts at our request pointed to the opacity the contracts created as a fundamental flaw. They afforded communities limited rights to scrutinise how their loans were being spent and how the companies were calculating costs and profits. An academic whose research focuses on smallholders, who did not want to be named, said that the “huge lack of transparency” was the “baseline issue”.

Several experts noted that the contracts also enabled the companies to profit from what the plasma produced, if things went well. But if it was not profitable, it was the villagers who would have to deal with potentially crippling debts. “From the company's perspective, it's all profit, no risk,” said Peter Batt, the agribusiness consultant. “And that's what I think is really fundamentally wrong with the way in which these contracts are written.”

Three of the companies we investigated — Cargill, Kuala Lumpur Kepong and KPN Plantations — insisted their legal agreements with cooperatives, which were not among those we obtained, had been witnessed or “endorsed” by the government and were in compliance with the law. Cargill said it was committed to ensuring its agreements with villagers are “clearly defined, documented, and legally established”, and KPN Plantations that the agreements were “fully understood by all parties involved”.

Genting Plantations, whose contract we did analyse, wrote that the agreement had been “vetted” by two government agencies and the cooperative. The bank insisted Genting act as a “proxy” for the cooperative, it wrote, because it was a guarantor for the loan. “Banks want to ensure that the loan is able to be repaid and [the company] is held responsible for the loan as well,” it said.

“Things can become a bit of a black box and either very legitimate or prone to abuse, depending upon the ethics and the transparency of the company itself."

While we were only able to obtain five contracts, the conditions they establish — particularly the control they afford companies and lack of transparency — have consistently been identified in plasma schemes by researchers, activists and even the Indonesian government anti-monopoly commission.

“Things can become a bit of a black box,” said Gary Paoli, director of the sustainable development consultancy Daemeter, who has carried out a series of studies on Indonesian smallholders over the past decade, “and either very legitimate or prone to abuse, depending upon the ethics and the transparency of the company itself."

All we got was dust

By 2017, Rita was growing frustrated. Seven years had passed since he had ceded his land to Palmdale. Oil palms stretched for thousands of hectares around Teluk Bakung. Trucks laden with fruit were passing through the village, but the villagers had yet to see any profits.

“All we got was dust,” he said.

The community was also slipping deeper into debt. Since 2014, Rita said, their loan had grown by almost $4m and now totalled more than $14m. The villagers had made several attempts, through both the cooperative and the district government, to pressure Palmdale to explain why they were getting nothing. But the company was stonewalling them.

Early one morning in April that year, his patience running out, Rita stopped a Palmdale truck loaded with five tons of palm fruit in front of his house. He confronted the driver, demanding to know if the fruit had been grown on his land. He would keep the truck, he insisted, until a company official came to explain where it had come from.

The truck driver did call Palmdale’s manager, but he in turn reported Rita to the police. Rita was arrested and, four months later, convicted of threatening behaviour. He was sentenced to a year in prison. “While I was in prison, all we could do was contemplate,” Rita told us. “All this time we’d relied on the regional government [to help us]. It turns out it was hopeless.”

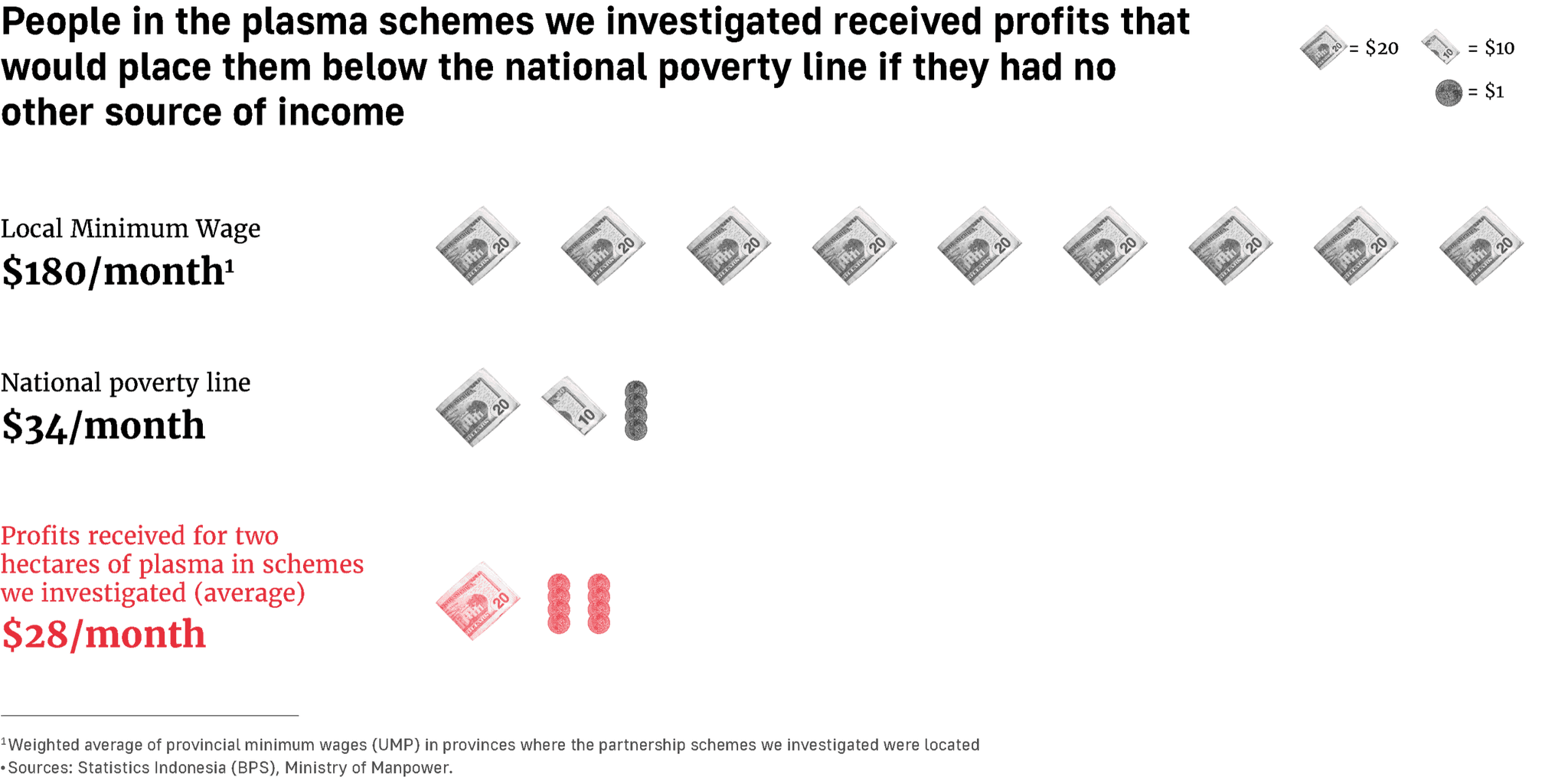

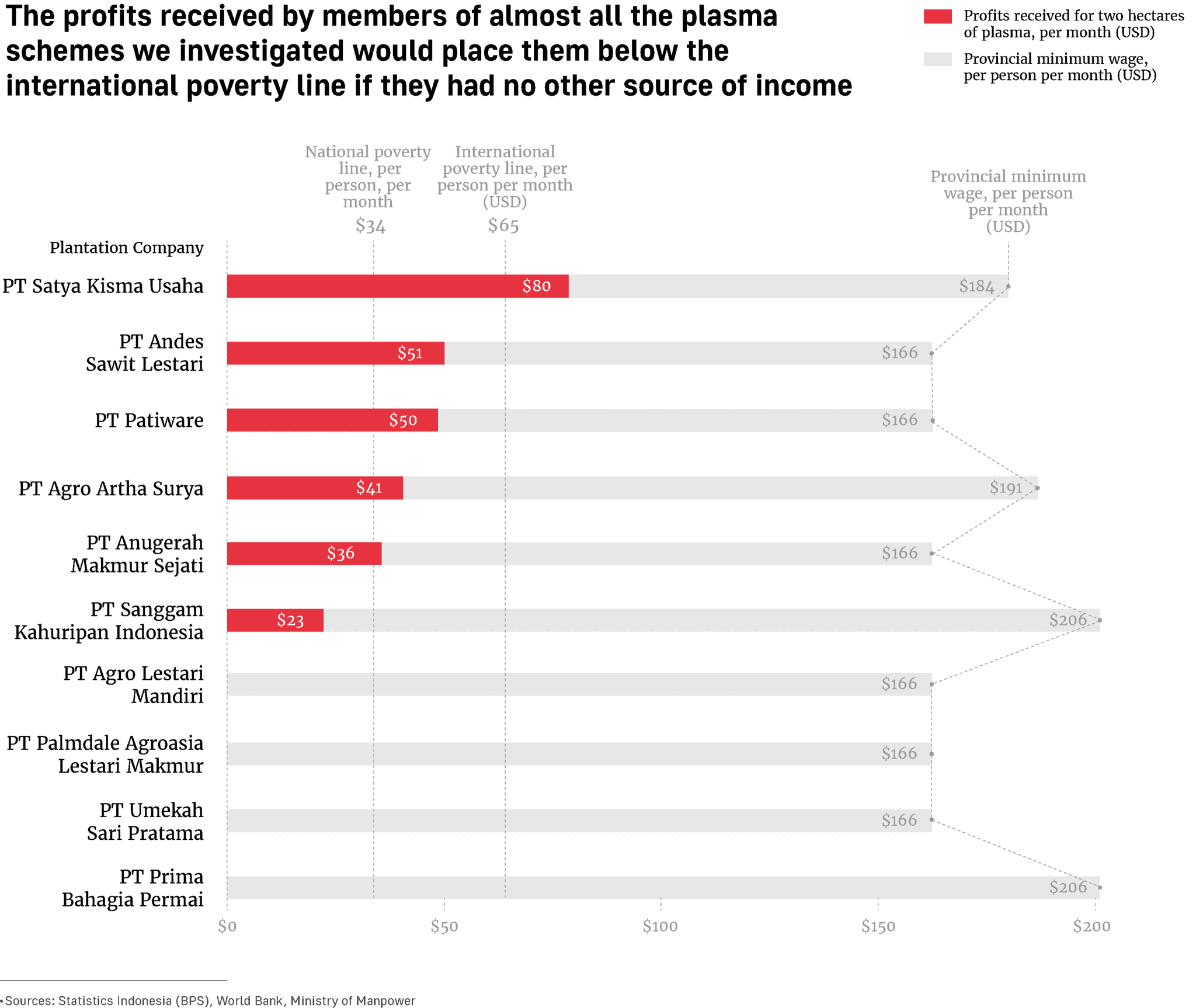

Palmdale was one of four cases we investigated where communities earned nothing from their plasma. But the others fared little better. On average, across the ten companies for which we obtained reliable data, people were receiving monthly payments of $14 per hectare.

In the communities we visited, households typically had around two hectares of plasma. With these payments, they would receive less, on average, than the poverty line set by the government and only 16 percent of the local minimum wage.

For people who retained some of their land or other sources of income, plasma could be a bonus. But for those who gave up all of their land, according to Tania Li, not receiving profits was a “catastrophe”. While studying plasma schemes, she found people living at “basically the poverty line”.

“It’s a terrible deal,” she said. “If you're somebody whose land has now been swallowed up by a corporation, and this dividend is all you have to live on, it matters hugely whether that amount is sufficient, and how it compares to what you would have had from an actual smallholding.”

The companies we investigated

The Gecko Project, Mongabay and the BBC sent reporters to communities, spread across five provinces, that had entered into partnerships with 12 palm oil firms. We identified these communities on the basis of media or NGO reports alleging that communities had not received plasma, or the profits from plasma.

Six of these 12 plantations were in West Kalimantan province, with three in North Kalimantan, and one each in Central Kalimantan, Gorontalo and Jambi provinces.

| Company name | Parent company |

|---|---|

| PT Patiware | KPN Plantation |

| PT Agro Lestari Mandiri | Golden Agri-Resources |

| PT Sanggam Kahuripan Indonesia | Dhanistha Surya Nusantara (owned by Makin Group until 2017) |

| PT Satya Kisma Usaha | Golden Agri-Resources |

| PT Anugerah Makmur Sejati | Evershine Asset Corporation |

| PT Palmdale Agroasia Lestari Makmur | Honor Ace Enterprises (owned by Gozco Plantations until 2017) |

| PT Umekah Sari Pratama | First Resources |

| PT Andes Sawit Lestari | Cargill |

| PT Globalindo Agung Lestari | Genting Plantations |

| PT Prima Bahagia Permai | Kuala Lumpur Kepong (owned by IJM Plantations until 2021) |

| PT Agro Artha Surya | Inti Agri Resources |

In ten cases, we were able to obtain sufficient data to draw conclusions about the profits cooperative members were receiving. In five cases, we were able to obtain information about the level of debt held by the cooperative.

Allegations of similar problems extended far beyond the communities we visited. A recent academic study examining 150 conflicts between communities and palm oil firms found grievances over plasma in 57 percent of the cases. In “many, if not most”, the communities were “disappointed” by the profits they were receiving. Our own scan of public reports over the past five years found communities across 17 provinces claiming they were receiving very limited or no profits from their plasma, with public complaints increasing in frequency over that period.

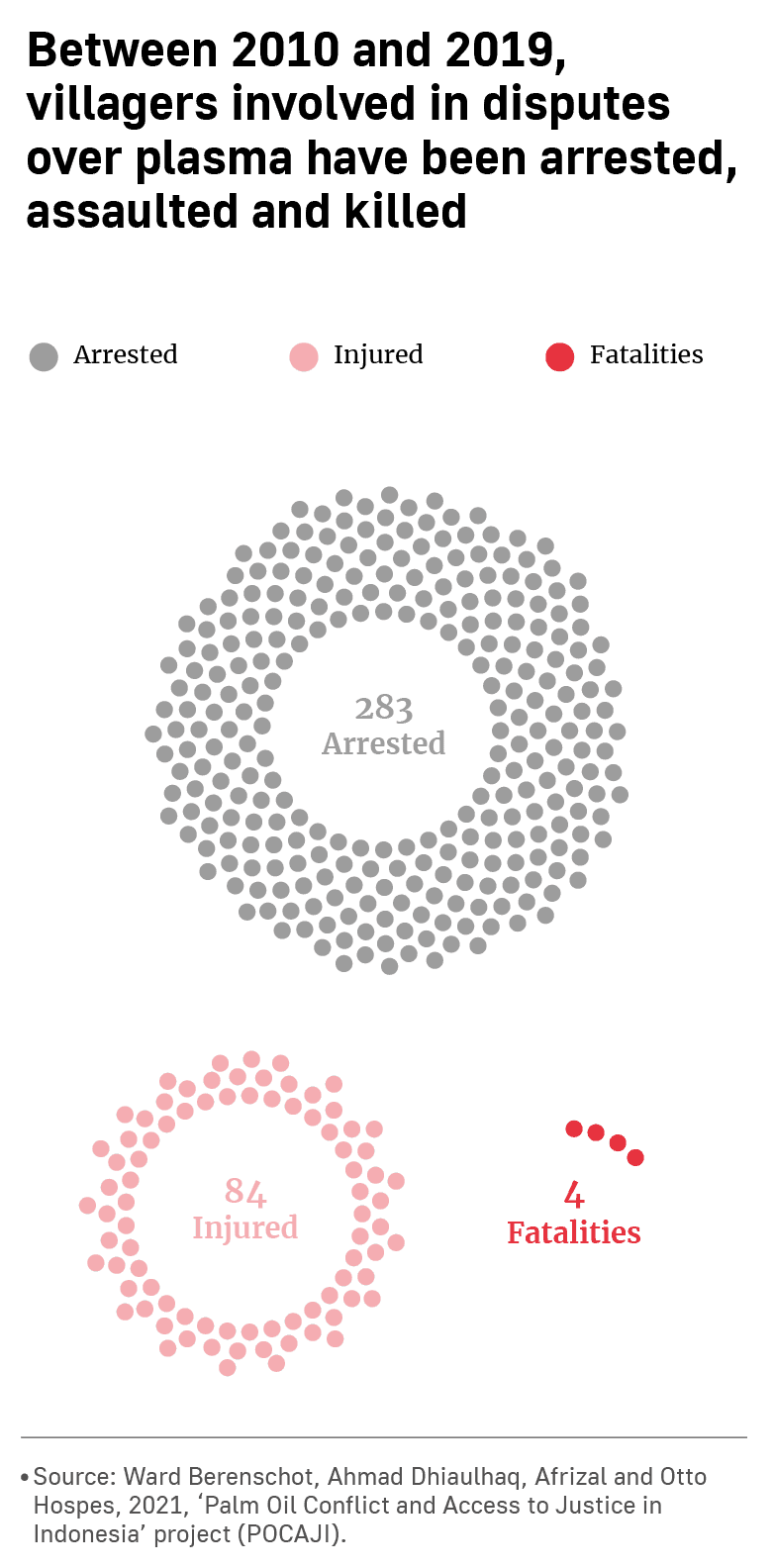

Rita’s decision to take direct action was not unusual. The academic study found that villagers had carried out demonstrations in 76 percent of cases; we found communities protesting in 33 cases.

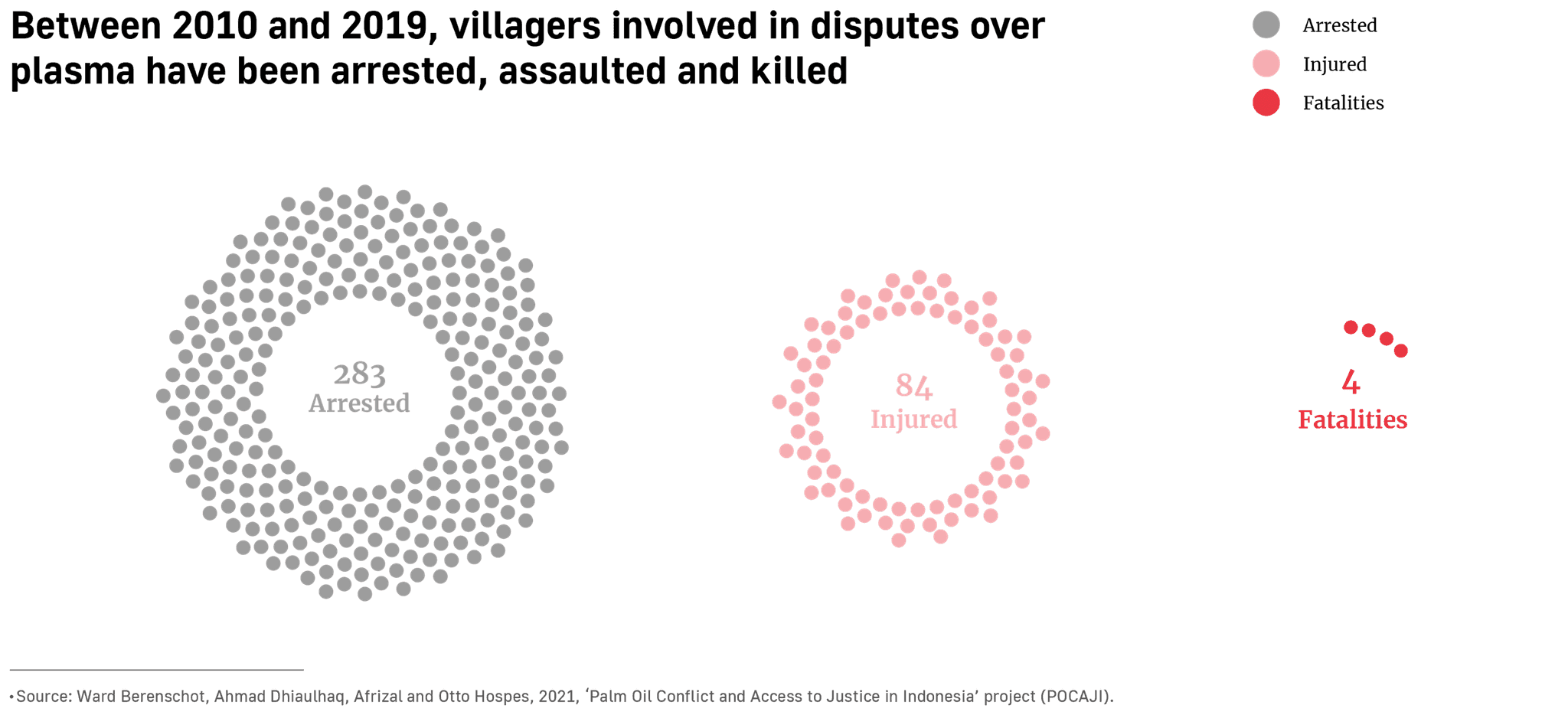

The response from the authorities and company security guards could be brutal. Villagers were subject to violence or, like Rita in Teluk Bakung, arrested. In total, the study found 283 people were arrested, 84 people injured and four people died in disputes involving plasma.

Companies told us complaints arose because communities were expecting to receive payments before plantations became profitable. “We are dealing with rural communities with high expectations of immediate returns, and narrow understandings of all other requirements,” one corporation wrote in response to our questions.

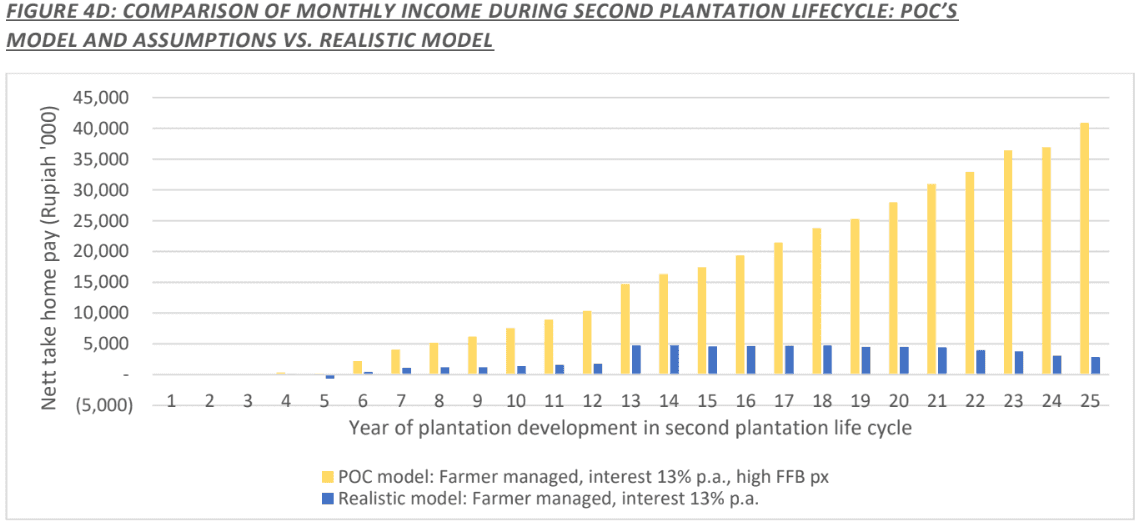

Industry observers and companies told us that communities should expect to receive some profits between five and seven years after planting. Loans should normally be fully paid off after 10 to 12 years, according to the companies we interviewed, at which point the profits would significantly increase.

But palm oil is not a risk-free investment. Land fires, fluctuating palm oil prices and excessive heat or rainfall could all hit revenues, according to Susanto Yang, an executive at Golden Agri-Resources, Indonesia’s largest palm oil producer and parent company of two of our case studies. This, he said, would extend the period it would take to pay down the debt.

“There are factors beyond our control,” he said in an interview. “What happens If there are unfavourable conditions? If prices fall, inevitably it will take longer.”

Our research suggested that if villagers had inflated expectations or limited understanding of the financial benefits of plasma, it may have been caused by the way the schemes were explained at the outset. We found three cases in which villagers claimed they were not told they would have to take on any debt.

“They said they would pay for all operational costs, no tax involved, but [there was] not a single mention of debt,” Siana, from West Kalimantan, told a researcher studying how the palm oil industry had impacted indigenous women.

In other cases, people were told they would receive far more than they eventually did. In the Sumatran province of Jambi, a team formed by a Golden Agri-Resources subsidiary to convince villagers to join a plasma scheme reportedly told them they would receive $300 each month or more. More than 12 years later the scheme was paying out less than a fifth of that, according to villagers we interviewed.

In Gorontalo, on the island of Sulawesi, cooperative managers and villagers said the company PT Agro Artha Surya told them they would earn $125 per hectare every month from a partnership. Cooperative documents show that around nine years later they were receiving just $21, on average — a fraction of what they were promised.

Piers Gillespie, who studied plasma schemes in West Kalimantan province, noted that firms can take a bullish approach while trying to convince villagers to sign up. “Often, what happens is that the plantation company very much over-promises the benefits that you can get from palm oil,” he said. “By the time the harvest is coming in, the promises that have been given to the local community just don't add up.”

According to one insider, Golden Agri may have deliberately fostered a false sense of how profitable plasma would be. In a 2020 academic thesis, Edwind Satyabrata, who has worked as an executive for Golden Agri since 2008, reviewed a financial model his employer had developed, estimating the future profits for members of a plasma scheme in Riau province, Sumatra. He found they had projected an “astronomical increase in income each year”.

But these projections were based on multiple “erroneous assumptions”, he wrote, some of which were “unsupported even by historical data”. He estimated that landowners would receive “significantly” less than Golden Agri projected.

Satyabrata wrote that it was “unclear as to why” such flawed figures had been produced. “Perhaps,” he speculated, “the [company] simply wanted to have a model that would show great success for the farmers, so that there would be no need to face the realities of the farmers’ issues, and thus absolve themselves from the responsibility of having to deal with the issues.”

Golden Agri did not respond to requests to comment on this allegation.

But inflated expectations do not fully explain the discontent of the farmers in the partnerships we investigated. In the eight cases in which planting had started 12 or more years ago, people were earning less than a dollar a day, on average. In seven of those cases, the profits would place them below the international poverty line if they had no other source of income. By this point, the palms should have reached peak productivity and the debts should mostly, or all, have been cleared.

Small-scale farmers who plant palm oil without the support of companies are theoretically at a disadvantage to those involved in corporate-run plasma schemes, lacking access to finance and technical expertise. But an economist who has studied these independent smallholders in Sumatra said that it would be “implausible” for them to earn “zero profit” from a ten-year old plantation.

Our analysis of data published in a 2020 study shows that between 10 and 20 years after planting, independent smallholders in Jambi province were earning, on average, $1,018 per hectare — six times the average profits in the cases we investigated.

Retno Kusumaningtyas, a researcher who has studied the financing of the palm oil sector, said that it would take “very extreme conditions” for a plantation to generate no profit after ten years. The plasma may have been developed improperly, using low quality seeds, or planted in acidic or swampy soils, she speculated. Or, she said, “someone is basically lying to you.”

Someone is lying to you

A white drone hovered above a plantation on the north-east coast of Borneo, one day in 2017. Its four rotors buzzing, it flew over rows of oil palms managed by a company, PT Sanggam Kahuripan Indonesia. Then, it came to a scrubby, barren patch of land: the plasma.

Eight years after the company began planting the plasma, the residents of Salimbatu village, in Bulungan district, were receiving the equivalent of $2.50 a month, according to Sahran, the cooperative’s secretary. “We had given up hope,” he told us.

The local plantation agency had tried to check the plasma before, according to Astrid Puspitasari, who was then working for the NGO Sawit Watch as part of the team piloting the drone. But, she said, the company had planted healthy palms along the road used by the government monitoring team.

“They didn’t see the real thing, only the camouflage,” she added.

The drone’s aerial image revealed in stark visual terms the contrast between the unkept plasma and the more verdant portion of the plantation benefiting the company.

Around the time that the drone mapping took place, the company behind the plantation - the Makin Group - offloaded it to another investor. Tan Tian Sang, the managing director of the new owner, confirmed Sawit Watch’s account. Over email, he described the plasma area as “completely neglected” and in the condition of a “secondary jungle”.

Makin Group, the company’s original owner, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The case in Bulungan points to a flaw in the partnership model. Villagers rely on companies to maintain the plasma efficiently, to ensure that it will produce enough fruit to pay down the loan taken out in their name and pay out profits.

But Zahari Zen, the academic and government adviser, has written that there has long been “a temptation and indeed a tendency” for companies to prioritise their own portion of plantations at the expense of plasma. The companies’ own plantations are “after all the ‘profit core’ of their operation,” he noted.

According to villagers and experts who have studied the sector, companies can neglect plasma plantations in multiple ways, all of which can suppress the profits received by communities.

Companies can manage plasma in ways that suppress profits

In partnership schemes, companies can, in practice, place the plasma where they see fit within their licensed area. According to a report by the nonprofits Forest Peoples Programme and Sawit Watch, "prime lands tend to be taken for [the company], while plasma lands are often developed far from settlements."

These areas can have less fertile soils. They can also be hilly or more challenging to access, increasing maintenance costs and making harvesting more expensive. In West Kalimantan, Piers Gillespie noted, one company he studied appeared to be failing to harvest areas of the plasma plantation that were difficult to reach. In three of the cases we visited, villagers said companies had failed to maintain access roads to the plasma plantations.

Once plantations are operating, communities and experts said, some companies fail to maintain the trees or plantation infrastructure. Zahari Zen, the academic, said that he had seen companies provide plasma plantations with only 70 percent of the fertiliser they used for their own plantations.

Genting Plantations, one of the companies that told us it agreed the location of the plasma with the cooperative, insisted that "most of the time" this resulted in the villagers getting the more productive land.

Officials in three plantation agencies said in interviews that they had seen companies fail to maintain plasma plantations properly. Samsul Kamar, head of the plantation office of Rokan Hulu district, in the Sumatran province of Riau, said that when they do so, “the result is an increase in debt, not income,” for villagers.

Local plantation agencies are responsible for assessing whether companies are managing plantations to government-set standards. But our interviews showed the scope and quality of this monitoring varied widely, with some agencies relying solely on reports from companies that included only basic details. Several officials said they lacked the resources to monitor every plantation.

Golden Agri-Resources: Partnership problems in Indonesia’s largest palm oil producer

PT Kartika Prima Cipta, a Golden Agri subsidiary, provided plasma using a partnership model to villagers in West Kalimantan's Kapuas Hulu district. According to two nonprofits, the Forest Peoples Programme and TuK Indonesia, who carried out research in 2013, villagers alleged that the company located the plasma in a hilly area far away from its mill, making it less profitable than the company's own estates because of the higher overheads needed to maintain and harvest the plantations.

PT Satya Kisma Usaha, a Golden Agri subsidiary, signed a contract with a plasma cooperative in Tebo district, Jambi province, in 2009. According to Fahmi, a customary leader in Muara Kilis village, the company has prioritised maintaining its own plantation over the plasma.

He said that the company had located the plasma in a hard-to-reach area of its concession and failed to maintain roads leading to it. Because company employees were paid by the weight of palm fruit harvested, Fahmi said, they had less incentive to harvest fruit from the plasma. As a result, according to the plasma cooperative's treasurer Abdul Kodir Jailani, "The fruit goes rotten and doesn't get picked up."

Susanto Yang, the Golden Agri executive, said that in the firm's plantations, "both [the company's plantations] and the plasma are built the same way. There is no difference. No stepson, no golden child. We have the same plantation and maintenance management."

In the absence of government oversight, it is largely the role of cooperative management — usually comprising a handful of individuals from the village — to hold companies to account.

Experts said the five contracts we obtained did not clearly stipulate what information companies were required to provide to cooperatives. One noted that most of the contracts did not require independent audits of companies’ spending, which they said could prevent villagers from identifying company mismanagement or overcharging.

In seven of the communities we visited, villagers said they struggled to get answers from cooperative managers as to why their profits were so low. In some cases, they alleged that the cooperative managers were failing to pass information on to them or even embezzling profits.

But some cooperative leaders said they could not answer people’s questions because they did not understand the financial information that companies gave them. Internal documents from one cooperative, in Central Kalimantan, showed that it asked a company to explain the meaning of the English word “outstanding” in the financial statements it received. Other cooperative managers said that companies withheld information from them, on topics ranging from the plantation’s production to its operational costs.

Susanto Yang told us that Golden Agri’s West Kalimantan-based subsidiaries, which he oversees, meets with cooperative managers regularly throughout the year. “That's where we report what happened, what the production results were, what the costs were, our future plans,” he said. “Everything is stated in these meetings, and we report it transparently.”

But in one Golden Agri-owned plantation we visited in Jambi province, PT Satya Kisma Usaha, three senior members of the cooperative said that they did not know the size of their debt. “The problem is in Satya Kisma Usaha,” said Mustafa Kamal, the chairman of the cooperative’s advisory body.

Gary Paoli, the consultancy firm director, said that cooperatives with “real leadership, courage and confidence” could demand transparency from companies. “But they can also be co-opted by companies and become one part of the mechanism for abuse,” he added.

While Palmdale was spending millions of dollars in loans issued to the community, in Teluk Bakung, the cooperative barely functioned. Court records show that it failed to hold a single annual meeting for its members in five years, during the critical period when the plasma was ostensibly being planted.

In multiple cases — including in Rita’s village, Teluk Bakung — there was so little transparency that villagers didn’t even know where the plasma was. Their plots were somewhere, unspecified, in the sea of a corporate-run plantation.

“All they have is a piece of paper,” said Astrid Puspitasari, the former Sawit Watch activist.

Only three of the companies we investigated, in addition to Golden Agri, responded to requests to comment on the limited profits their plasma schemes were generating. KPN Plantation said the cooperative was still paying off investment costs and that the plasma is also in “marginal soils”, resulting in “below target” productivity. It noted that local villagers can generate additional income as employees in the plantation.

First Resources wrote that the plasma “conversion” had only taken place in 2018, so revenues were still being used to pay off debt and interest. The prevailing regulation stipulates that companies should plant the plasma at the same time as their own portion of the estate. But satellite imagery shows that First Resources began planting in 2010, leaving a lag of several years before they broke ground on the plasma. The company said that it started discussions with communities in 2009, but it “took years” as it was trying to obtain consent properly.

The final company, Cargill, disputed the data we obtained from villagers in its plasma scheme. Our figures indicated they were earning only $306 for two hectares of plasma, a quarter of the local minimum wage, each year. Cargill said they were earning two percent more than the minimum wage, on average, but did not respond to requests to share specific figures.

Four of the companies we investigated, in addition to Golden Agri, disputed the assertion that their plasma schemes lack transparency. Cargill, KPN Plantation, Kuala Lumpur Kepong and First Resources all said in statements that they regularly provided financial information to cooperatives, including how they calculated revenues and the status of their loans. First Resources and Kuala Lumpur Kepong also said that the location of the plasma had been agreed with the cooperatives.

In Bulungan, where the plantation was photographed by drone, the villagers were finally able to expose the company to scrutiny after eventually obtaining a map showing where the plasma was. Tan Tian Sang, who took over management of the company, suggested the former owners may have deliberately withheld the information from the villagers “so that manipulations can be easily carried out”.

Tan Tian’s company, at the behest of the local government, agreed to “rehabilitate” the plasma at its own cost. It was a rare example of a case where a community had obtained irrefutable evidence that a company had neglected plasma, with the support of both an NGO and the local government, and found a receptive audience in the form of a new owner.

While their situation had improved, it still left the villagers far short of where they had hoped to be. Sahran, the secretary of the cooperative, told us that by 2022 each family should have been earning between 3 million to 4 million rupiah each month, around $190 to $250. Instead, they were receiving profits of just $11. “It’s actually still small, compared to what it would be if the plantation was managed well from the beginning,” he said.

Sahran’s cooperative only began paying down its debts in 2022, he said, 13 years after the plasma was first planted. In some partnership schemes, the communities’ debts were not going down, even slowly. They were rising.

Our money has been stolen

One morning in May 2019, hundreds of Teluk Bakung residents marched to Palmdale’s office. Chaining its doors shut, they performed a customary ritual known as pamabakng, traditionally deployed when grave disputes have arisen.

“Our money has been stolen,” read one banner they pasted on the building, alongside a picture of a bag of cash.

A new investor had bought the plantation two years earlier, then added another $3.4 million to the cooperative's debt without the villagers’ knowledge. By 2019, the villagers had discovered that they now owed the bank more than $18 million.

“When something like that happens, chaos ensues,” said Herkulanus Roby, a man from Teluk Bakung now in his early 30s, who was among the protesters. Then a foreman on Palmdale’s plantation, he had also handed over his land to Palmdale.

As a company employee, he told us, he should not have joined the protests. “But on the other hand, as a plasma farmer, I had to fight for my rights,” he said.

The villagers had been afforded a rare glimpse of the state of their debts. Most of the people we interviewed could not get details of how much their communities owed, or when it was expected to be paid back. Those that did found they were still in the millions of dollars, approaching or even beyond the decade mark.

One factor that can contribute to debts remaining stubbornly high is that, as in Teluk Bakung, companies retain the ability to pile on more debt.

In at least three of the communities we visited, companies were paying communities small sums of money, between 12 and 13 years after they started planting. But these were not profits. They were known as “bailouts”, paid out while the plasma remained unprofitable, then added to communities’ existing debts.

Susanto Yang, the Golden Agri executive, said his firm sometimes offers these payments because it is a “responsible company” that wants “people to continue to earn an income even if the cashflow is negative.” He pointed out that Golden Agri does not charge interest on the loans.

Eddy Martono, secretary-general of GAPKI, Indonesia’s largest palm oil industry association, said in an interview that its members issue bailouts in a “very transparent” way. But smallholder groups and villagers said that companies frequently fail to tell communities that bailouts are actually additional loans.

"In many cases, there is no transparency," said Marselinus Andry, head of advocacy at the oil palm smallholders’ union, known as SPKS. "The farmers get a shock when they realise they’re being charged for a new loan, on top of their existing debt.”

The Palmdale case showed that companies could also, in practice, take out more debt in the name of the cooperative. We could find no evidence that Palmdale was entitled to do so according to its contract, and the company did not respond to multiple requests to comment for this article. But it was not the only case we found where this had happened. In 2015, the Supreme Court ruled that the plantation company PT Tunjuk Langit Sejahtera had illegally obtained an additional $11.6m loan in the name of a plasma cooperative, without its consent.

The root cause of the sky-high debts may just be a system that fails to protect villagers from incompetence or misfortune. Some of the experts who reviewed the partnership contracts noted that whatever happened — whether the plantation was mismanaged, there were fluctuations in palm oil prices, or even natural disasters — the cooperatives would be expected to bear the cost. One, who was not authorised to speak on the record by their employer, noted that land fires — a perennial occurrence in Indonesia — posed a serious threat to any plantation. But the contracts included no protections against this risk.

"If there is a disease outbreak or large fire,” they said, “whose plantation will the company save first? Its own, from which it derives more profit and will have to fully pay to replant? Or the plasma, which is less profitable and will be paid by cooperatives anyway?”

"In many cases, there is no transparency. The farmers get a shock when they realise they’re being charged for a new loan, on top of their existing debt."

Genting Plantations, one of the few cases in which we obtained debt data, said in a statement that the debt remaining high was not an indication the plantation had not been “well managed”. It wrote that it was dependent on the productivity of the plantation, which was in turn dependent on “uncontrollable factors such as weather, flood, social matter etc. [sic].” As the guarantor of the loan, it noted, it would also impact the company if the plantation was badly managed.

After the protest in Teluk Bakung, the police arrested Roby and two other villagers. In court, the company claimed that the protesters’ closure of its office had cost it 33 billion rupiah, around $3.6m. A district court sentenced all three to prison, with Roby handed a ten-month term.

A year after he left prison, Roby was still locked into his contract with Palmdale. His arrest and incarceration had a chilling effect on his ability to press the company.

“We can’t take any more action in case we get tangled up in criminal acts again,” he said. “The situation is even more fatal.”

We’re taking our protests to the courts

In August last year, the Supreme Court in Jakarta — Indonesia's highest court — handed Rita an important victory. Some four years earlier, while languishing in jail for stopping Palmdale’s truck, he struck upon the idea of suing the company.

The premise of the suit was simple. Rita had signed a contract handing over his land to Palmdale, in exchange for the profits it would generate, but the community had received nothing but “bailout” payments that added to their debt.

The case was first heard in 2017, in the district court in Mempawah - the same court that had jailed Rita months earlier. Four other people from Teluk Bakung joined the suit. The villagers testified that Palmdale rebuffed their efforts to find out where their plots were. The court heard that the cooperative, set up to represent the interests of the farmers, failed to hold an annual meeting in five years.

Palmdale’s manager told the court that in 2015 and 2016 the firm had transferred profits amounting to approximately $0.50 and $4 per farmer for the entire year, respectively. Since then, he claimed, it had run at a loss.

But the judges, in their ruling, criticised the firm for a “lack of transparency” over what the plantation was actually producing. They held that Palmdale had defaulted on its contracts with the villagers and declared them void.

“It turns out that someone was listening to our prayers, us little people,” Rita told us.

Watch BBC Indonesia’s film about the Teluk Bakung case:

Palmdale appealed the ruling through ever higher courts. The case finally arrived at the Supreme Court where, on August 10th, the judges rejected Palmdale’s call for a judicial review. After more than ten years, Rita was finally free of the burden the partnership placed on him. “I didn’t want to pass my problems with the company on to my family,” he said.

But the case involved just a handful of the villagers in Teluk Bakung. More than 900 villagers remained locked into the partnership with Palmdale. Others viewed the judicial system as out of their reach.

“We also want to do what Rita did, but are we strong enough?” said Roby, who had been jailed for protesting against Palmdale. “We can see that Rita's case took years. And it costs a lot to fight against a company.”

For villagers unable to access justice through civil courts, there is an alternative — the Indonesia Competition Commission, known as the KPPU. For the last four years, the KPPU has been investigating whether some plasma partnerships violate a 2008 law that prohibits large businesses from “controlling” smaller partners. “Dozens of investigations are underway,” Guntur Saragih, the commission’s deputy head, told us in an interview.

According to a legal expert who gave evidence at a KPPU hearing in 2022, a company is likely to be legally “controlling” a plasma cooperative if, among other things, the cooperative has no access to information about the plasma’s location or development costs.

After investigating cases reported by communities, or those it identifies itself, the commission can issue written warnings encouraging companies to “change their behaviour”, according to Guntur. Some companies have responded by providing cooperatives with information about the location of the plasma and improving their financial transparency, he said.

If these efforts fail, the KPPU can haul a company in front of a council of its commissioners. If they decide a company has broken the law, the KPPU can issue a fine of up to 10 billion rupiah (approximately $650,000) or order other government agencies to revoke its licence.

A recent KPPU investigation found that plantation firm PT Bulungan Citra Agro Persada had been illegally controlling a plasma cooperative through a partnership scheme. After repeatedly ignoring the KPPU’s requests to resolve the situation by, for example, sharing financial information with the cooperative, PT Bulungan faced the commission for a formal hearing this June.

The commission ultimately ruled that it was no longer acting illegally because, just two months before the hearing, the company had terminated its contract with the cooperative and handed the plasma to the villagers to manage themselves.

Still, the KPPU identified multiple flaws in the way the scheme was run that mirror those in the partnerships we investigated. The cooperative did not know where the plasma was located or understand the costs involved in developing it. The cooperative chairman testified that he didn’t know how to read financial reports from the company “due to limited education” and had received no training to help him do so.

Like the partnership contracts we examined, PT Bulungan’s contract gave the company full authority to manage the plantation and its finances — an indication that a company may be controlling a cooperative, according to the judgement.

The KPPU said it would follow up on the findings from our investigation.

How do the cases we investigated link to markets?

We examined public disclosures by three of the world’s largest consumer goods firms to identify whether they had sourced palm oil from the cases we investigated. Eight of the ten plantations for which we obtained data on profits received by cooperative members have supplied one or more of these consumer goods firms.

We wrote to the three consumer goods firms named in this article, outlining the allegations against the companies in their supply chains.

Kellogg's said it has followed up with its suppliers and has been "assessing actions" it can take to "further support the resolution" of problems with plasma in its supply chain.

Nestlé said it requires its suppliers to comply with the law, works with them to "improve social and environmental practices" and is helping them "make progress on the requirements specific to plasma palm plantations."

Unilever wrote that it requires suppliers to comply with the law. The company said that it has "reached out" to Golden Agri "to better understand the allegations and challenges in meeting the government regulation on plasma provision."

In the wake of our first article on plasma, in May, the national government announced a major audit of the palm oil sector. This was driven by multiple concerns, including a recent scandal over companies evading export restrictions, but the exploitation of smallholders was among them.

According to their public statements, officials are examining companies that have failed to provide plasma at all. They also appear to be setting their sights on problems that are emerging through partnership schemes. At a parliamentary hearing in the district of West Kutai, in September, legislators said they had asked auditors to investigate cases in their jurisdiction, after discovering communities were facing “enormous” debts and little profit. “If [they] find indications of violations, especially crimes, it is clear they should be prosecuted,” said Ridwai, who leads a committee focusing on the palm oil industry in the district.

For some villagers, whatever comes out of the audit will likely arrive too late. They have given up hope of receiving any money, and simply sold off their share of the plasma in the hope of ridding themselves of the burden. “They become workers for the company,” said Albertus Wawan, a cooperative manager from West Kalimantan. “It’s really sad. Working on their own land, on the plot of land that they just sold.”

In Teluk Bakung, the hopes of a brighter future a plantation firm created, more than a decade ago, have dimmed. Rita, who became head of the village in 2019, said people seek work outside the village. It suffers from flooding, which one activist group has attributed to the plantations around it.

The Supreme Court decision has left Rita in a strange limbo. While his agreement with the company has been cancelled, its palms still stand on his land. He and his co-plaintiffs still wait for the land to be formally handed back, more than a year after the final ruling.

When he gets his land back, he may use it to cultivate his own oil palms. “If I plant oil palms, it won’t be tied to a company,” he told us. “Not using this ‘cooperation’ method, lying to each other.”

The plaintiffs had demanded 50 billion rupiah in compensation, around $3.6 million. But this was turned down by the judges on the grounds that they had not provided any calculations indicating how they arrived at the figure. It left them with nothing to show for their years in the partnership.

Still, the ruling gave Rita a renewed faith in the possibility of justice, and the Indonesian judicial system.

“As village head, I’ve said we’re not playing around with demonstrations anymore,” he said. “We’re taking our protests to the courts.”

Reporting team

The Gecko Project

Margareth Aritonang, Tom Johnson, Safrin La Batu, Ian Morse, Gilang Parahita, Leoni Susanto, Rio Tuasikal, Tom Walker.

Mongabay

Ari Anggara, Jaka Hendra Baittri, Elviza Diana, Philip Jacobson, Yusie Marie, Aseanty Pahlevi, Yitno Suprapto, Suryadi, Taufik Wijaya.

Independent

Eko Nurcahyono, Sarjan Lahay, Boris Pasaribu, Fatahur Rahman, Petrus Suwito, Masrani Tran.

BBC News

Aghnia Adzkia, Astudestra Ajengrastri, Rebecca Henschke, Muhammad Irham, Haryo Wirawan.

Graphics

Thibi (charts) DataWrapper (maps)

Illustration

Chuan Ming Ong.