- The Indonesian government stripped back rules protecting the environment to expedite a plan to ramp up food production.

- A firm run by allies of the Minister of Defence has positioned itself to profit from the programme and is seeking $2 billion in investment.

- Analysts say numerous rules have been broken and there are huge conflicts of interest at play, as the government sets its sights on the forests of Papua.

When the Indonesian government announced ambitious plans to ramp up domestic food production as the pandemic set in last June, officials claimed that it would not lead to “environmental destruction”.

Instead, as COVID-19 threw the world’s supply chains into disarray, officials would ward off the threat of an impending food crisis by boosting crop yields and promoting modern, environmentally sensitive farming techniques.

But within five months, workers acting under the instructions of the Ministry of Defence had fired up their chainsaws to cut down orangutan habitat in Borneo and replace it with a giant plantation.

The story behind this plantation reveals how the ministry has exploited regulations that were drafted hastily during the pandemic, stripping away environmental safeguards and opening up vast new areas of land for agriculture.

An investigation by The Gecko Project and Tempo discovered that the ministry moved so fast that it failed to comply even with these scaled-back rules, potentially illegally clearing hundreds of hectares of rainforest.

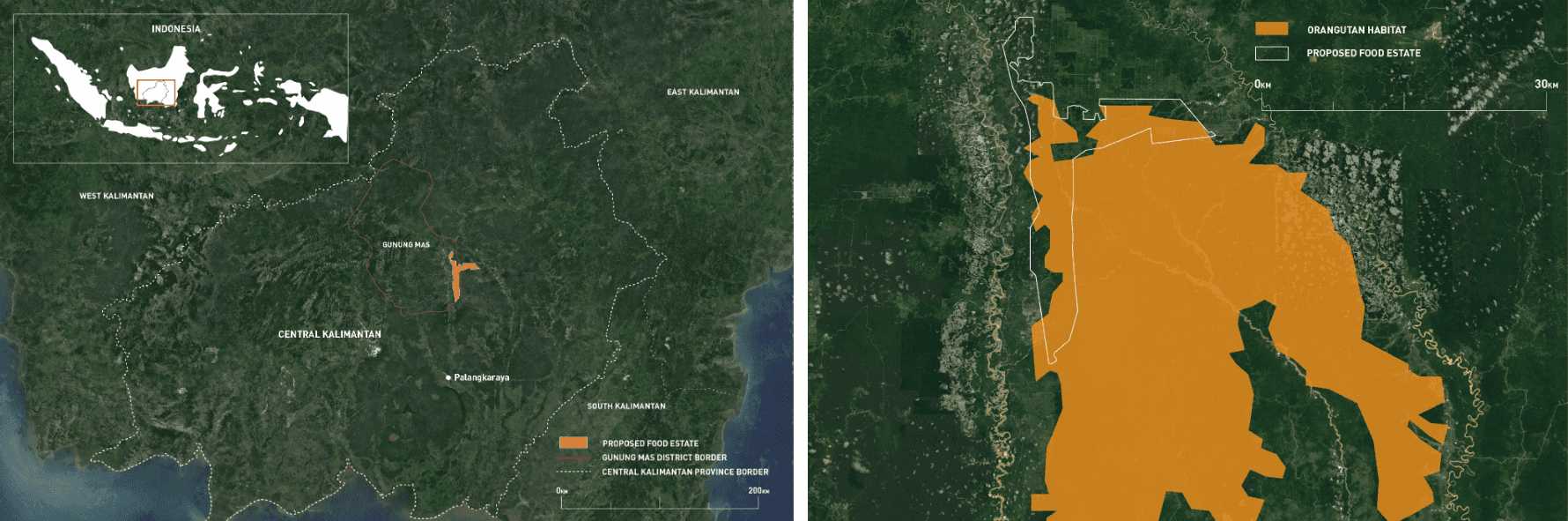

The plantation in Borneo, which could take over 32,000 hectares of land that for now is still mostly rainforest, represents just a fraction of the ministry’s ambitions. After Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto was handed a central role in the “food estate” programme, his officials drew up plans to plant more than one million hectares of cassava, a root vegetable, across the country.

The investigation also discovered evidence that the Ministry of Defence is attempting to steer food estate projects, which are potentially worth billions of dollars, to a company with no discernible track record in developing plantations. The company, PT Agro Industri Nasional, or Agrinas, is staffed by individuals from Prabowo’s inner circle.

Agrinas is owned by a non-profit foundation also controlled by Prabowo, with the support of a string of retired and serving top-ranking military officers. Analysts have questioned whether the ownership structure is legal, because it appears to violate rules that are meant to ensure such foundations serve charitable purposes.

They also say Prabowo’s close relationships with Agrinas’s executives and board members generate serious conflicts of interest.

Agrinas and the Ministry of Defence deny partnering on the food estate programme. Despite these denials, we found that Agrinas has sought $2 billion in investment from a foreign government by referencing its privileged access to the programme and connections to Prabowo.

Our investigation also found that the defence ministry is now moving ahead with its plan to develop further plantations in Papua, a biodiversity hotspot in the east of the country that holds part of the largest tract of intact rainforest in Asia.

The ministry’s efforts there are being led by a retired naval officer, who says the labour on plantations will be provided by young Papuans recruited into a newly-formed reserve military corps. Soldiers have already been deployed in support of the programme in Borneo.

The involvement of the military in Papua raises serious concerns, critics say, because the military has a track record of committing human rights abuses against the region’s indigenous population in the interests of advancing natural resource extraction and plantation projects.

The ministry has already presented plans to plant rice and cassava on thousands of hectares of forest and indigenous land in Merauke, a highly militarised district in the furthest eastern reaches of the country. But it has failed to share these plans with the people that they most affect. Local Papuan communities, whose legal rights have been eroded by the new regulations, remain in the dark.

“We’re racing against time”

President Joko Widodo, known as Jokowi, launched Indonesia’s food estate program on the back of warnings of an impending global food crisis as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The spread of the virus could be “catastrophic” for millions of people across the world living on the cusp of hunger, the chief economist at the World Food Programme said in April 2020.

UN bodies asserted that the problem was not how much food was being produced. Rather, the danger was that food might not get to where it was needed, as supply chains were gummed up by border restrictions and workers were forced to stay at home, and it could become too expensive for families hit hard by the economic slowdown.

But reducing Indonesia’s reliance on food imports by producing more domestically is a perennial obsession of the nation’s political class, one that arose as a topic of debate in the last two presidential elections. Jokowi instructed his ministers to deliver on this ambition and address the impending pandemic-driven crisis by growing more staple foods such as rice.

The licensing process for agricultural plantations was lengthy. Companies were required to get approval from numerous government agencies, consult with local communities and carry out environmental impact assessments. Large areas of land and forest were off-limits to agriculture, to protect watersheds and maintain forest cover.

Officials in the capital, Jakarta, got to work designing regulations that would cut through the bureaucracy. As the new rules began to emerge, observers suspected the government was prioritising speed over legal principles and the environment.

For Adrianus Eryan, a legal researcher at the Indonesian Center for Environmental Law, or ICEL, the first sign was an environment ministry “operational plan” that he found online in mid-2020. The document outlined plans to turn vast swathes of land in four provinces into “food estates”.

Normally, Adrianus said, such guidance would come after regulations were released. There was no legal basis to enact the changes the ministry had laid out. “This was a bit strange, because it was backwards,” he added.

When the first food estate regulation was enacted in October 2020, it revealed the potential scale of the changes. The new regulation handed the government the ability to use potentially millions of hectares of land previously unavailable for food plantations, including areas designated as protected forests.

“This was a bit strange, because it was backwards”

The regulation allowed the government to implement these changes with few checks and balances. It demanded a suite of documents, including management plans and environmental permits. But most of these can be produced after land is opened up. Rezoning areas for the food estate only requires a “commitment” to complete them.

The principal requirement is for officials to carry out a strategic environmental assessment, known by its Indonesian acronym as KLHS. The assessments are lengthy analyses that involve extensive public consultation and are used to inform long-term planning.

But the regulation also allows for a “rapid” KLHS, a format that was developed for use in emergency situations. This format relies on the judgement of experts over empirical evidence, according to an ICEL analysis. ICEL found that rapid KLHS “tend to be speculative and leave a lot of room for uncertainty”, and questioned the justification for their use in the food estate programme.

Walhi, a national green group, called the rapid assessment “baseless” and urged the ministry to repeal the entire regulation. This July, the regulation was updated, but there were few substantive changes.

Yeka Hendra Fatika, a member of the national Ombudsman, which monitors how the government delivers public services, said that even a year after the programme was announced it remained unclear who was running it and how it would be financed. The lack of formal planning created the “potential for maladministration”, he added.

Within two months of the first food estate regulation being issued, the fears of a global food crisis had waned, according to a World Bank analysis published in December 2020. Countries had started exporting crops again and the trade in most staple foods was expected to increase for the first time in four years.

“The structural problems can’t be solved by large-scale land clearing”

The problems for poor Indonesian families, according to the World Bank, were high food prices, caused by a range of issues including processing and transport costs, and limited access to nutritious foods like fruit and vegetables. The food estate programme, which principally targeted production of rice and cassava, would not directly address either problem.

“The structural problems can’t be solved by large-scale land clearing,” said Bhima Yudhistira, an economist and director of the Center of Economic and Law Studies.

In its December 2020 analysis, the World Bank cautioned that the success of the food estate would depend, in part, on “the management of environmental and social risks”. By then, however, the government had begun to cut back the social and environmental safeguards that might slow it down.

In an interview this September, Moeldoko, Jokowi’s chief of staff, said the legislative process was justified by the urgency of the “food crisis”.

“We are racing against time,” he told us. “If the intention is to serve the people, the safety of the people is the highest law.”

“Many safeguards ignored”

Much of the early attention on the food estate programme focussed on plans to intensify rice production in a region of peat swamps in the south of Borneo. Critics noted quickly that it revived a notoriously disastrous plan in the same location, two decades earlier, that had led to the swamps being drained, generating vast greenhouse gas emissions but very little rice.

The Ministry of Environment and Forestry was keen to allay concerns that the new programme would also result in environmental damage. It would instead focus on the rehabilitation of protected areas that had been illegally deforested, as well as agroforestry, which weaves crops through forests without clearing them.

“Another key concern for us is to ensure that no Bornean orangutan habitat is targeted,” said Siti Nurbaya Bakar, the environment and forestry minister.

But president Jokowi had also handed responsibility for the programme to his Minister of Defence and former election rival, Prabowo Subianto. In the same month that Jokowi toured the peatlands in southern Borneo, military officers and defence ministry officials were meeting with the local government 150 kilometres north, in a district called Gunung Mas.

There, indigenous Dayak communities live along broad rivers that meander south from the mountains in the centre of the island, through rainforests and on to the Java Sea. The ministry set its sights on a stretch of wilderness east of the Kahayan River, where locals gather food, rubber and wood.

“It’s all wrong. The community is pushing us for answers”

In interviews with our reporters, village leaders recounted meetings with ministry officials and a senior military officer in July, just one month after the food estate was launched. The visitors from Jakarta had explained their intention to establish a plantation to help secure Indonesia’s food needs. But the details remained vague. The villagers weren’t told where the project would be, or when it would start.

Within a few weeks, Prabowo submitted a request to the environment ministry to establish a food estate nearly half the size of Jakarta, the capital city, in Gunung Mas. At the time, no regulation had yet described what a food estate area was, much less how it could be created.

Overlaying the borders of the proposed site with satellite imagery reveals that the majority was rainforest at the time the proposal was made. According to assessments endorsed by the Indonesian government, most of the area is orangutan habitat.

“At the beginning, they didn’t tell us that it would be as large as 30,000 hectares,” said Mine Yantri, a village head who joined the meetings in July. “We couldn’t really oppose a government programme.”

The clearing began in mid-November, when the food estate regulation was just three weeks old.

Though they had been involved in some early meetings, the communities living in nearby villages still had little information. Sigo, an indigenous leader from Tewai Baru village, was on a routine trip to gather wood when he found his path blocked by soldiers guarding the land. Villagers began accusing community leaders like Sigo of selling off their land behind their backs.

“It’s all wrong,” Sigo said. “The community is pushing us for answers.”

The defence ministry did not hold its first public consultation for a strategic environmental assessment — required to rezone the land — until February, three months later. By that point, more than 600 hectares had already been cleared.

A presentation given to a parliamentary hearing in March 2021 indicated that the ministry had still not yet met the conditions needed to rezone the land. The land was categorised as ‘permanent production forest’. Under a long-standing principle of Indonesian forestry law, such areas cannot be converted to agricultural plantations.

Adrianus, from ICEL, said the sequence of events indicated that there was “likely a violation” of the law. “With this food estate there have been many safeguards ignored,” he added. “The KLHS was ignored, the community was not involved, the process was designed behind closed doors.”

The Ministry of Defence told us it had started land clearing by making use of a 2018 regulation that allows, in emergencies, the “borrowing” of land zoned for other uses without changing its status. It said they had then “made adjustments” when the 2020 food estate regulation was enacted. The clearing was “based on instructions from Jokowi during a cabinet meeting.”

“The process was designed behind closed doors”

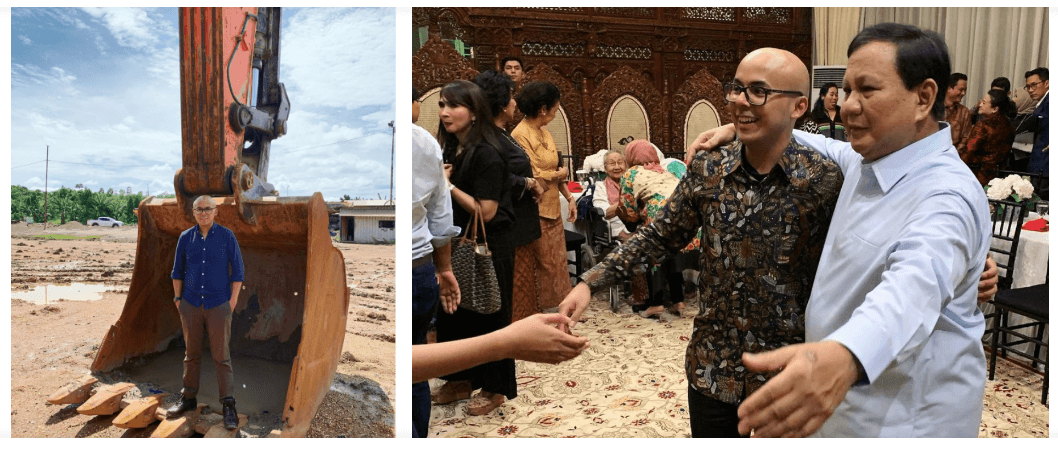

When our reporter visited the site this August it was guarded by soldiers. Moeldoko, Jokowi’s chief of staff, told us the use of active duty soldiers was justified by the 2004 National Army law.

That law requires approval from the national parliament for their deployment, but we could find no record it had been given. Two security analysts told us the deployment was likely a violation of the law.

Despite the large amount of forest already cleared, by August this year only around 30 hectares of cassava had been planted. Our reporter found stalks that were wilted and yellow. Many appeared to have died.

Prabowo’s ambition is to plant more than a million hectares of cassava, using the root vegetable as a substitute for wheat as part of efforts to reduce Indonesia’s reliance on imports. The defence ministry also believes the crop can be used for a range of other products unrelated to food, from biofuels to pharmaceuticals.

But cassava plantations are not easy to establish, according to Reinhardt Howeler, a scientist who spent decades researching the crop. Smallholders produce most of the world’s supply, he said, and most plantations larger than a few hundred hectares are so labour-intensive that they are not economical. A 32,000 hectare cassava plantation would be the largest Howeler has heard of by a factor of at least five.

Professor Achmad Subagio, a cassava expert who was working on the ministry’s project in Gunung Mas but hadn’t visited the site since February, said that cassava requires intensive care for four months after planting. “If there is no maintenance fund, they will be skinny for sure,” he added.

In its haste, the ministry had cleared the rainforest before it had the budget to establish its plantation. Almost a year after it started cutting trees, it said it was “still waiting for the regulatory process and the budget” for the programme.

Return of the Jedi

By January this year, the protagonists of the food estate programme were looking outside Indonesia for ways to bankroll their ambitions.

A firm called Agrinas was pitching for the South Korean government to invest in the project, according to a document our reporters found. The figures were eye-watering: Agrinas was seeking almost $300 million for the Gunung Mas plantation alone.

Agrinas stated in the pitch that it was owned by the Ministry of Defence and reported directly to Prabowo. It said it aimed to become the world’s largest “end-to-end” producer of cassava flour, with one million hectares of plantations and 34 factories across Indonesia.

Curiously, for a project intended to help feed Indonesians, Agrinas also proposed that the investment could “improve South Korea’s food security”.

In response to our questions, both Agrinas and the Ministry of Defence denied that they had partnered on the food estate programme. Agrinas denied pitching to the Korean government but did not answer questions about the investment document.

Our investigation found evidence, however, that Agrinas has been involved almost from the moment the programme was launched. While the precise parameters of that involvement are unclear, the evidence suggests the company is central to the Ministry of Defence’s aspiration to develop more than one million hectares of land.

This could allow Agrinas to benefit from billions of dollars in revenues, in its own analysis. We found that the firm’s ownership structure effectively gives control and oversight of the company to Prabowo and a coterie of his political allies. Many of them share an affiliation to Prabowo’s political party and some also have positions within government.

Muhamad Haripin, a Jakarta-based defence and security analyst, described the overlaps as “a death triangle”.

“The processes involving business, private and public interests are blurred,” he said. “Everything goes through that one door. People can quickly change their clothes, acting as if serving public interests while in fact they are serving the interests of their own groups.”

Agrinas was set up by a charitable foundation whose purpose, until recently, was to help retired and serving soldiers with housing and education. That focus began to shift in April 2020, when a retired general named Musa Bangun became head of the board of directors and Agrinas was incorporated. Musa Bangun also holds a senior role in Prabowo’s political party.

At the start of 2021, legal documents show the foundation was renamed the Development of Potential Defence Resources Foundation. Its remit was expanded to include “organising business activities” and supporting the government “in the field of national defence”. A string of new military figures joined the board, including the current head of the armed forces and Prabowo.

“People can quickly change their clothes, acting as if they’re serving public interests while in fact they are serving the interests of their own groups.”

Foundations can hold equity in private companies, but must abide by strict rules in doing so. Those rules appear to have been broken in this case.

According to a 2001 law, a foundation’s shares in a company can’t amount to more than 25 percent of the foundation’s total assets. The Development of Potential Defence Resources Foundation’s shares in Agrinas represent almost half of its stated assets, according to an internal document we obtained.

Leadership positions in Agrinas are filled by members of Gerindra, the political party headed by Prabowo. They include several people from his inner circle. Rauf Purnama, a businessman in his late 70s and the CEO of Agrinas, ran for legislative office as a Gerindra candidate in 2019 while working on Prabowo’s presidential campaign as an expert adviser.

Deputy CEO Dirgayuza Setiawan, now in his early 30s, began working for Prabowo soon after graduating from an Australian university. He served as his lead speechwriter, and told The Jakarta Post in 2014 that his father had been Prabowo’s personal doctor.

During Prabowo’s presidential run in 2014, he reportedly referred to Dirgayuza as one of his three “Jedi knights”: young, foreign-educated Indonesians who had forged personal connections to the retired general. The other two, Sudaryono and Sugiono, are commissioners of Agrinas, roles that require them to provide oversight of the directors who manage the company on a day-to-day basis.

Sugiono is also now a member of the national parliament and sits on the commission that oversees the defence ministry’s budget, despite Indonesian law prohibiting politicians from taking jobs related to their legislative duties.

“It’s clear the conflict of interest there is huge,” said Ronald Rofiandri, a legal analyst from the Center for Indonesian Law and Policy Studies.

In response to our questions, Agrinas said that Sugiono had resigned from his positions in the company. Public records accessed on 1 October show he remained listed as a commissioner.

Agrinas became mired in controversy within three months of its incorporation.

In July 2020, Tempo reported that fisheries minister Edhy Prabowo — himself a Gerindra politician — had lifted a ban on exporting lobster larvae and issued licenses to four companies with connections to Gerindra. Agrinas, which had no discernible experience in the lobster or export industries, was among them.

The scandal forced Edhy to resign, and by November he had been arrested by Indonesia’s anti-graft enforcement agency, the Corruption Eradication Commission, known as the KPK. This July he was convicted of taking Rp. 25.7 billion ($1.8 million) in bribes to lift the export ban, and sentenced to five years in prison.

Agrinas, however, was not charged by the KPK. As the case against Edhy was unfolding, the firm was helping to get the Ministry of Defence cassava plantation underway.

“It’s clear the conflict of interest there is huge”

Sources in Gunung Mas, site of the cassava plantation, placed Agrinas together with the ministry there in 2020. Jaya Samaya Monong, the district head, said that Agrinas and the ministry were working as “partners”. A lieutenant colonel working on the project described the company as the “managers” of the plantation.

The investment proposal for the South Korean government also credits Agrinas with developing the Gunung Mas plantation. “We are on our way to deliver [sic] our first factory and plantation in Central Kalimantan with full endorsement from the President,” it states, above a map showing the boundaries of the project.

Metadata in the document shows that its author is deputy CEO Dirgayuza.

Yetty Komalasari Dewi, an associate law professor at the University of Indonesia, questioned how Agrinas could represent the defence ministry when its legal structure meant that profits would not automatically flow back to the state.

“The ministry is part of the government,” she said. “So why doesn’t it instead set up a state-owned enterprise? Sorry, for me this is fatal.”

“Sorry, for me this is fatal”

When asked what Agrinas’ role was in the food estate programme, the ministry wrote that it “has never appointed a private partner to handle CLS,” referring to its programme to build up food reserves. Agrinas wrote: “Until now Agrinas has never been a program partner for the Food Estate at the Ministry of Defence.”

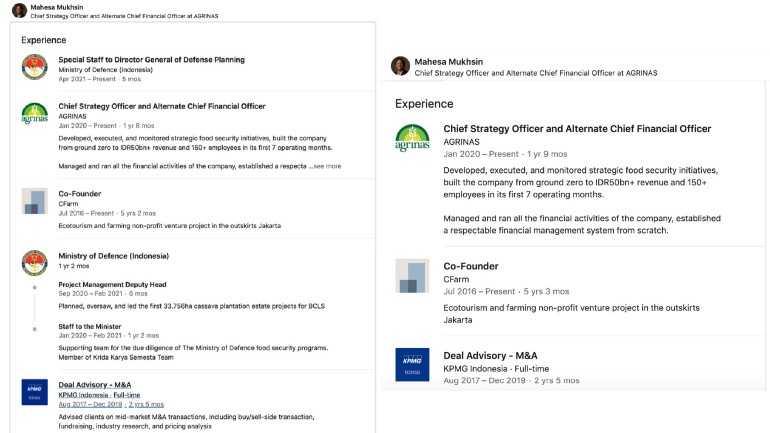

Whatever the structure of the relationship, we also found evidence that Agrinas staff have concurrently worked on the food estate project for the Ministry of Defence.

Chief among these individuals was Mahesa Mukhsin, who joined the firm soon after completing an MBA at Oxford University. As well as being Agrinas’ chief strategy officer since January 2020, Mahesa claimed on LinkedIn that while in a senior role at the ministry at the same time, he “[p]lanned, oversaw and led” the development of its first cassava plantation.

After we submitted questions to Agrinas, Mahesa deleted all references to his role at the Ministry of Defence on his LinkedIn profile.

Rauf, Dirgayuza, Sugiono and Mahesa did not respond to requests for an interview or comment on a detailed list of our findings.

The military’s involvement in the private sector is not new. Through Indonesia’s three-decade military dictatorship, companies allowed the military to take shares in exchange for protection, with the officers “just siphoning off money”, said Jacqui Baker, a political scientist at Murdoch University.

Research by Human Rights Watch found that by the early 2000s the military’s interests spanned “the full range of the economy”, from banking to golf courses. Controlling its businesses through foundations set up by the government for social purposes was a method of choice. It allowed them to operate independently of government while also benefiting from state funds.

“Given Indonesia’s history of military businesses this sets off a huge number of red flags”

In 2006 a former head of the military told parliament that even when they were led by retired officers, “practically speaking…the military command feels they own the foundation.”

The practice was tolerated to help the military pay for itself, according to Transparency International. But it was plagued with corruption, enabling senior commanders to control illegal logging and amass vast fortunes by soliciting bribes. In 2004, a law instructed the government to take over or close down companies owned directly or indirectly by the military within five years.

“Given Indonesia’s history of military businesses,” Baker said, Agrinas’s ownership structure “sets off a huge number of red flags.”

The question of why Agrinas was given — or claimed — such a central role in the project is difficult to answer. Around the time the food estate was announced, it set up a flashy website that laid out a bold ambition to become “the leading integrated agribusiness, bioenergy, and conservation company in the Asia Pacific Region.”

But its track record during its short lifespan speaks of a company flailing around for an identity. It has presented itself as a conservation organisation that can help generate and sell carbon credits through conservation projects that reduce deforestation, while simultaneously engaging in a project to cut down forest in Gunung Mas.

Its Facebook page promotes its own brand of rice and luxury hampers, and it sells frozen lobsters on Tokopedia, a popular online shop. In July 2020, an Agrinas employee sought to hawk nutmeg, pepper and cloves on behalf of the firm on a Chinese trading board.

What’s clear is that cassava plantations are central to its ambitions. It has planted cassava at its research site on the outskirts of Jakarta, wants to develop cassava plantations and processing factories across five islands, and promotes its own brand of instant noodles made from the root vegetable.

In a July 2020 opinion article published on a news website, Agrinas director of marketing Harryadin Mahardika wrote that cassava “could become a new prima donna that spurs economic growth from agrobusiness as in the booming palm oil industry in the early 1980s.”

“There are many other competitive advantages that can be explored to strengthen the government’s food security programs,” he added. “The key lies in the solidarity of all parties involved, under one command, namely Prabowo Subianto’s.”

“What does it have to do with the military?”

By August this year, the Ministry of Defence had found more land for the food estate programme. This time it was in Papua, in the far east of Indonesia, a region replete with savannas and rainforests, home to curious creatures like the tree kangaroo and birds of paradise.

Since at least September 2020, Muhaimin, a retired navy officer, had been travelling across Papua to meet district governments, working under orders from Prabowo — he claimed — to get new plantations going.

In Nabire, a coastal district in the northwest, he said the army would clear the land, then hand it over to Agrinas for planting. “It will be a collaboration between the regional government and the Ministry of Defence, represented by PT Agrinas,” he said. In Asmat, a district of peat swamps in the south, Muhaimin told officials that young Papuans could be recruited into “Komcad”, a newly-formed military reserve corps, and work the ministry’s cassava and rice fields.

At a Zoom meeting with military officers and local officials on 12 August, Muhaimin unveiled the results of a strategic environmental assessment that had been carried out for two rice and cassava plantations in a district called Merauke. Though Papua holds more plant diversity than any other island on the planet, the assessment recommended the clearance of more than 18,000 hectares of rainforest.

The assessment did come with some warnings. The project could lead to river pollution and land conflicts. Some 15,000 hectares of the land, it estimated, belongs to local communities.

According to a record of the meeting we obtained, Muhaimin told the attendees that the proponents of the project hadn’t yet met with the communities who would be affected by it, due to the pandemic. The communities were not invited to the virtual meeting, either.

Now that the assessment is complete, the decision to rezone the land rests with the Ministry of Environment and Forestry. Muhaimin told us Agrinas would be involved in the project “if it goes smoothly”. He declined to offer more details.

For local activists, the prospect of soldiers descending into the indigenous territories of Papua to develop plantations has ominous precedents.

For decades the region has been highly militarised, ostensibly in response to a simmering Papuan independence movement. But the army and police have also been used to suppress opposition from communities to corporate-led projects that threaten their land and rainforests.

“There are many cases in which the military has carried out violence against indigenous Papuans,” said Aiesh Rumbekwan, an activist from the Papua arm of the environmental group Walhi. “There’s trauma there.”

Observers have documented extensive human rights abuses inflicted on indigenous Papuans by the military, including kidnapping, torture and extrajudicial killings. Between 2018 and 2020, Amnesty International documented 47 suspected unlawful killings by security forces in the region.

“When it comes to land acquisition, if the military is involved with companies, the community can’t say anything,” said Franky Samperante, the director of the non-profit organisation Pusaka, who has worked extensively with Papuan communities to help protect their rights. “They can’t speak.”

As a result of persistent government efforts to promote industrial-scale agriculture in the region, some sugar, palm oil and timber firms have gained a foothold. The government has promoted these plantations as a means of bringing economic development to a part of the country with little infrastructure and low levels of education. But research has shown that the developments can have a perverse effect.

Academics, non-profit organisations and a previous investigation by The Gecko Project, have found that plantations have reduced the food security of some Papuans, by destroying the rainforests and wild sago groves people rely on for subsistence and livelihoods. Communities living around food plantations have become reliant on handouts from companies and the government, and have been forced to adopt less nutrient-rich diets.

Under the food estate programme what legal safeguards did exist have been reduced, and the military is now directly involved in the plantations. To Aiesh, these features are likely to exacerbate, not curtail, the problems.

“It’s just a land grab under the guise of food security,” he said. “The food estate is about agriculture. What does it have to do with the military?”

To see other articles plus films and photos from The Gecko Project as they come out, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube. Sign up to our mailing list here. The Gecko Project stories are available in Bahasa Indonesia at our Indonesian site here.

4th November 2021: This article originally stated that Indonesian foundations are limited to owning at most 25 percent of a company. The law actually states that the shares in any company cannot exceed 25 percent of the foundation’s assets. The article has been corrected.