- Royal Golden Eagle, one of the world’s largest producers of pulp and paper, made a high-profile commitment to keep rainforests standing, turning its back on years of unsustainable practices.

- An investigation by The Gecko Project finds that Royal Golden Eagle appears to be behind a string of secretive companies that have been clearing large swathes of orangutan habitat in Borneo.

- The investigation adds to mounting evidence that Royal Golden Eagle, and the super-rich Tanoto family that owns it, are operating a network of “shadow companies” that allow it to evade its own sustainability commitments.

This investigation was published in collaboration with Bloomberg News.

Anderson Tanoto says he wants to bring a millennial sensibility to the family business.

Now in his mid-30s, Anderson is a scion of the Tanotos, an Indonesian business family that owns a sprawling conglomerate named Royal Golden Eagle. RGE, one of the world’s largest producers of wood pulp and paper, sells an array of products to international brands, ranging from palm oil to Unilever and P&G, to viscose to the clothing firm Esprit. Headquartered in Singapore, it has a major presence in Indonesia, where it has a chequered environmental record—something Anderson has pledged to address.

“My generation, 30-something, we have to ask a lot of questions,” he said, at a Bloomberg event in 2022. “Our goal is to really make sustainability widespread.”

Anderson has worked hard to cultivate an image as a young leader of the sustainable business movement. Over the last four years he has hopped from glitzy conference to conference, discussing biodiversity at Davos, conservation at Cop26 and solar panels at the G20 business summit.

Under his leadership, RGE has publicly committed to protecting rainforests in Indonesia, ensuring its continued access to “sustainable” markets — and Anderson’s invitations to the top table at climate summits.

“We have to run our business, but we also have to protect the landscape around us,” he told a rapt audience at a nature documentary premiere in 2021, standing in front of a ten-foot-tall photo of a Sumatran tiger.

But according to people who worked for him, at the same time as he was trumpeting RGE’s sustainable credentials, Anderson was also overseeing another quite different business—a “shadow company” group called Borneo Hijau Lestari (BHL). BHL’s subsidiaries have consistently ranked among Indonesia’s top deforesters for pulp and paper in recent years, destroying swathes of rainforest and the habitat of the critically endangered Bornean orangutan.

Interviews with nine former employees of BHL provide evidence suggesting that RGE – and Anderson Tanoto personally – were controlling the company as its subsidiaries cleared vast swathes of rainforest. The employees’ accounts add to mounting evidence that RGE has sought to circumvent its own sustainability policies – operating one public arm that leaves forest standing, and another secretive arm that is leading the deforestation charts.

In response to a request for comment on the findings from our investigation, RGE denied that BHL and its subsidiaries are owned by, or under the control of, the company or its shareholders.

“RGE does not operate what you have claimed to be a shadow supply chain, and steadfastly upholds sustainability commitments across all companies in the RGE Group, particularly its no deforestation pledge,” it added.

The company declined to comment on the accounts of the former employees, on the grounds that “it would clearly be inappropriate for us to comment on allegations about the plantation activities or actions of other companies we have no ownership or control over or business association with.”

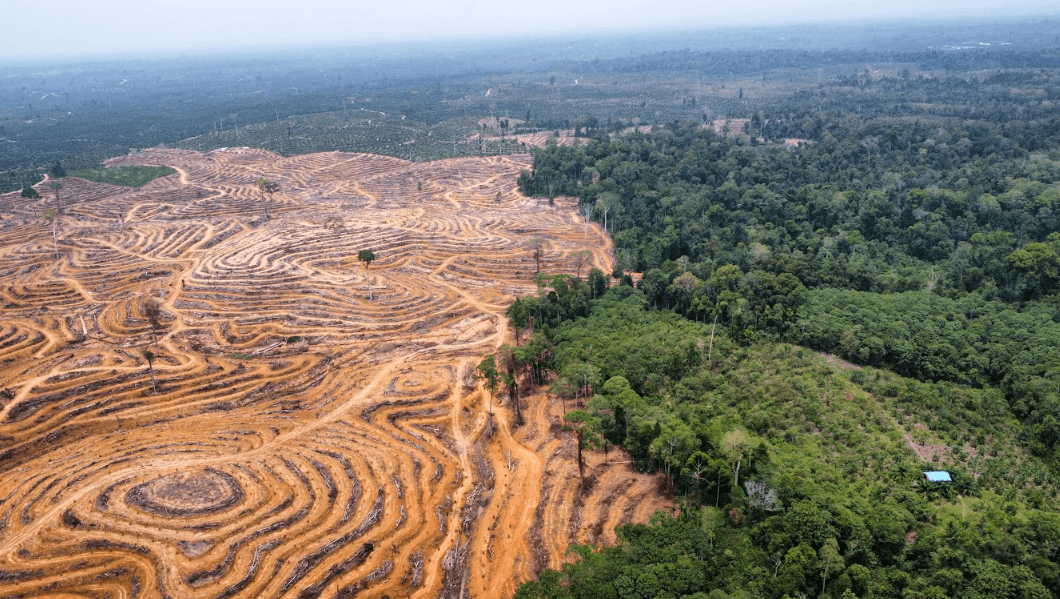

Over the past five years, one company has consistently been near the top of Indonesia’s deforestation league tables. Since 2019, Industrial Forest Plantation (IFP), which operates a timber plantation in the centre of Borneo, has destroyed an area of forest a third of the size of New York City, according to satellite imagery analysis by deforestation monitoring consultancy TheTreeMap.

Industrial Forest Plantation is one of six companies that form the BHL group. BHL has its own logo and website. But its owners make use of offshore secrecy jurisdictions, impeding efforts to determine who they are. The paper trail runs back to the Pacific island nation of Samoa, which allows people to register companies while keeping their identity hidden from prying eyes. BHL did not respond to a request to comment on The Gecko Project’s findings.

“Nobody knows who’s behind companies in Samoa - not even the Indonesian government,” said Syahrul Fitra, a senior forest campaigner at Greenpeace.

A 2021 analysis of corporate records by AidEnvironment found links between BHL and RGE, including that two of the first three directors at BHL’s majority shareholder had held senior positions at RGE. RGE stated at the time that it did not have “any connection” to BHL, which has also been known as Nusantara Fiber.

However, testimony from company insiders seems to suggest clear links between RGE and BHL, and that the two groups shared management personnel and structures.

The Gecko Project interviewed nine people who worked at BHL and its subsidiaries between 2015 and 2024, ranging from junior staff to managers with strategic responsibility for a plantation’s operations. Of the seven that said that they knew the identity of the BHL companies’ real owners, all held the view that they were the Tanoto family.

In the early 2020s, a BHL employee named Asep was working for BHL in a remote lowland area of eastern Borneo when he was asked to prepare for a visit from the company’s owner – who, his manager said, was Anderson.

Two other former BHL employees told The Gecko Project that between 2018 and 2023 they prepared for multiple visits by Anderson. Anderson arrived by helicopter, the employees said. One said his manager told him that Anderson had come to “oversee” the company’s land.

“I thought it was normal,” Asep said. “I mean, we’re talking about the company owner, who has power and capital. Of course he would visit by helicopter.”

“This is really, really strong evidence that RGE and BHL are connected,” said Syahrul, who reviewed The Gecko Project’s findings. “Why else would an RGE boss, a high-level person, come to a concession like that?”

RGE told The Gecko Project that it has “a wide range of formal and informal contact” with companies and individuals across Indonesia, for reasons including supplier due diligence, sharing knowledge and skills, and identifying opportunities for conservation and restoration. It said that it “would be illogical and without basis to infer anything more from any such contact or association beyond standard business conduct.”

Cecep, who spent several years working for BHL in a senior position, said that BHL took pains to cover up its links with RGE, with BHL staff urging employees not to mention the conglomerate on LinkedIn. “We knew that it shouldn't be exposed by the media,” he said. “We understood the consequences.”

Two employees said their managers told them BHL was owned by RGE. Another, when interviewed for a job at BHL, found their interviewer introduced themselves as an RGE employee.

The employees noted that many aspects of BHL and RGE’s operations were kept separate. For example, one employee explained that BHL and RGE companies did not hold regular meetings together. “That’s the system within [RGE],��” he said. “We’re sort of compartmentalised.” But the fact it was a part of the RGE conglomerate was common knowledge, supported by their experiences at the company. “It was kind of obvious,” one recalled.

A range of internal documents, employees said, had headings from RGE companies or had been sent from company offices. “On the top left there’s the RGE logo, and then the [BHL] logo at the top right,” an employee said of one BHL file.

There was also evidence suggesting that RGE staff had some oversight of BHL. One employee said staff from an RGE subsidiary visited from headquarters to “teach us”, while another described seeing a plantation audit conducted against “APRIL’s standards”. APRIL is an RGE group member that runs its Indonesian pulp and paper business.

Three of the staff interviewed by The Gecko Project worked under a BHL director called Andrea Gunawan, with one describing him as a former executive at RGE and the right-hand man of Sukanto Tanoto – RGE’s owner and Anderson’s father. “He was very smart,” one employee said of Andrea. “He is a trusted person [within RGE].” Andrea Gunawan did not respond to a request for comment on our findings.

Official sources also provide some evidence of operational links between BHL and a company associated with the Tanoto family. Between 2018 and 2020, documents submitted to the Ministry of Environment and Forestry show, a plywood mill operated by the company Asia Forestama Raya received natural forest timber from three separate BHL subsidiaries. According to Greenpeace, Sukanto Tanoto part-owned Asia Forestama Raya through a holding company from 2008 until July 2023, when his shares were transferred to a company registered in the British Virgin Islands, a secrecy jurisdiction.

RGE did not respond to this allegation.

For RGE, any association with large-scale deforestation could have serious commercial implications. In 2015, the conglomerate committed to end deforestation across its supply chain following a series of NGO campaigns that had named APRIL Indonesia’s top deforester for pulp.

Responding to our findings, RGE described APRIL as an industry leader on environmental protection, stating that independent audits showed there had been no deforestation anywhere in APRIL’s supply chain since 2015. It said that APRIL regularly monitors deforestation risks across its entire supply chain.

RGE also highlighted APRIL’s commitments to conserve forests, highlighting that the company currently manages 360,000 hectares of conservation forest across Indonesia, including a large-scale project to restore peatlands in Sumatra.

The conglomerate continues to sell products to brands like P&G, Unilever and Esprit - all of which have pledged to eliminate deforestation from their operations.

But RGE is still chasing one mark of recognition that it is a “sustainable” company. In 2013, APRIL was disassociated from the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), a leading – if frequently criticised – sustainability certification body, in the wake of allegations of deforestation in Sumatra by the nonprofits Rainforest Action Network (RAN), WWF Indonesia and Greenpeace. Since then, APRIL has been unable to sell FSC-certified products.

RGE has been working with the FSC to try and regain certification since 2016, it said in a statement. The FSC is currently determining whether to reassociate with APRIL – a step towards certification and access to new, lucrative markets.

This year the FSC published a list of companies it considers part of the RGE group, but did not include BHL. Nonprofits have criticised that decision, claiming that it disregarded evidence of links between RGE and alleged “shadow companies.” In an email, the FSC told The Gecko Project that it now will be conducting an independent external review to assess whether RGE controls a series of entities, including several alleged “shadow companies.”

The FSC defines a company as part of a corporate group if the group “controls” it, taking into account management overlaps, operational links, and whether offshore firms are used to hide ultimate ownership. The FSC’s definition is based on guidelines developed by a coalition of nonprofits called the Accountability Framework Initiative, or AFI.

"It would certainly appear that RGE and BHL are under common control.” Amanda Gore, forensic accountant.

“The Gecko Project's findings provide preliminary evidence under the AFI's framework to suggest that RGE is a controlling entity of BHL,” said Amanda Gore, a forensic accountant who focuses on issues involving both environmental and financial crime in Africa and Asia. "It would certainly appear that RGE and BHL are under common control.” Further investigations, she said, might involve analysing BHL’s ownership and its operational practices.

If RGE is ultimately deemed to control BHL, the conglomerate’s hopes of FSC certification could hit the buffers. According to FSC rules, no company within an FSC-associated corporate group can have deforested land after 2020.

But The Gecko Project found evidence suggesting close links between RGE and other companies that have cleared huge areas of rainforest since then.

In 2021, Industrial Forest Plantation was overtaken in the league table of Indonesia’s leading deforesters by another company: Mayawana Persada. Since then, Mayawana has cut down more than 40,000 hectares of forest, including large areas of orangutan habitat, in the west of Borneo.

“Mayawana Persada and Industrial Forest Plantation have been by far the worst deforesters in Indonesia over the last five years, in any sector,” said David Gaveau, of the deforestation monitoring consultancy TheTreeMap. Mayawana continued to clear rainforest this year in defiance of an Indonesian government order.

Deforestation by Mayawana and Industrial Forest Plantation could spell disaster for Borneo’s rapidly disappearing orangutans. According to AidEnvironment, the two firms’ concessions contain the most forested Bornean orangutan habitat of any industrial tree company in Indonesia. An orangutan presence has been confirmed in areas neighbouring Mayawana’s concession, said Caitlin O'Connell, deputy director of the Gunung Palung Orangutan Conservation Program.

Neither Mayawana or IFP responded to requests for comment.

“If you remove enough forest [in Mayawana’s concession] you might see a pretty rapid decline in the orangutan population,” O'Connell said, explaining that orangutans have been known to kill each other when forced together into smaller areas. “You’re not only removing their resources, you’re also shifting their social dynamics in ways that are potentially very deadly.”

Mayawana’s ultimate owners are also obscured behind companies registered in Samoa and the British Virgin Islands. But in March, a group of nonprofits including Auriga, Environmental Paper Network and RAN published allegations that Mayawana is also “related” to RGE, citing numerous overlaps in staff, as well as management and supply chain connections. Although RGE denied that it has any relationship with Mayawana, The Gecko Project’s interviews lend weight to these allegations.

In the early 2020s, as Mayawana was on its way to becoming Indonesia’s leading deforester, two BHL employees told The Gecko Project that they were sent to work at Mayawana. “Because it was still new, we were invited there to help develop the company’s systems,” one told us, explaining that they were sent to ensure Mayawana was following the same processes as BHL.

Andrea Gunawan, who employees described as a senior executive at BHL, told Greenpeace in 2023 that he now directs operations at Mayawana. One employee said that Andrea had taken multiple BHL employees to Mayawana when he left. “It’s like a train: the carriages would follow wherever the locomotive goes,” they said. Documents submitted to the government show that – like BHL – Mayawana recently provided natural forest timber to Asia Forestama Raya, the company that Greenpeace reported was part-owned by Sukanto Tanoto until last year.

RGE told The Gecko Project that Mayawana Persada “is not under the control or ownership, directly or indirectly, of RGE and/or RGE’s shareholders”. Mayawana did not respond to a request for comment.

More senior BHL employees, who had sight of how the conglomerate was run, said there was an organisational structure that encompassed RGE and its alleged shadow companies. “RGE is a business octopus,” one employee said, describing BHL and Mayawana as part of the company’s Kalimantan “division”.

Two BHL employees said this grouping also included Adindo Hutani Lestari – another company that has cleared thousands of hectares of forest since 2020. The Anti Forest Mafia Coalition, a group of NGOs, has alleged that Adindo is linked to RGE. One BHL employee reported using an internal IT system that allowed them to view plantation data from APRIL’s operating arm RAPP and three other companies: BHL, Mayawana and Adindo. Another said he had been deployed to several of these firms to “learn and teach” systems that the companies had to use.

RGE stated that its organisational structure does not include a “Kalimantan division”. It said that Adindo is a “long-term supplier” to APRIL and added that external assessments have shown that Adindo is compliant with RGE’s sustainability policies. Adindo did not respond to a request for comment, but has previously denied allegations that it has ownership or operational links with RGE or the Tanoto family.

If RGE is deemed to have hidden its links to shadow companies such as IFP and Mayawana, “it would cause massive issues – they would lose access to deforestation-free markets,” said Anna Schoemakers, general director of AidEnvironment.

This year, major palm oil buyers dropped the plantation company First Resources from their supply chain after an investigation by The Gecko Project found extensive evidence suggesting it had secretly controlled shadow companies that have cleared large areas of rainforest. An investigation commissioned by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil or RSPO, an industry body, is ongoing.

As evidence mounts that plantation companies are clearing forests through shadow arms while presenting themselves as “sustainable”, RAN has called for major international firms to investigate shadow company allegations themselves rather than relying on bodies like the RSPO and FSC to do so.

“We're in a time of climate crisis and a biodiversity crisis, and the biggest cases of deforestation in Indonesia are from shadow companies,” said Gemma Tillack, forest policy director at RAN. “We need to see brands developing clearer policies and procedures to address deforestation within corporate groups in their supply chain.”

After it was presented with the findings of our investigation, Unilever, which sources palm oil from a company in the RGE group, said that “these allegations are serious as they are linked to active forest destruction at an alarming scale”. But it had also received a denial from RGE that it owned or controlled BHL, Mayawana or Adindo. Unilever said it had requested that RGE conducts an “independent verification” and that “transparency and continued engagement is in the best interest of all parties.”

Esprit did not respond to a request to comment on The Gecko Project’s findings. P&G said that it does not source wood pulp from tropical rainforests or Indonesia.

RAN is one of a group of nonprofits including Auriga and Greenpeace calling on the FSC to suspend the process of RGE’s reassociation. In response to questions from The Gecko Project, the FSC said that it took shadow company allegations seriously, and that it would commission further reviews of a corporate group “when new information about corporate structures makes this relevant.”

Greenpeace’s Syahrul Fitra called for the Indonesian government to challenge RGE to declare all its connections. “The government needs to take serious action,” he said. “It’s something they can do right now. RGE is trying to cheat the system.”

Read more reporting from The Gecko Project on corporate accountability here.

Join The Gecko Project's mailing list to get updates whenever we publish a new investigation.

Header image: Deforested land in a concession belonging to Industrial Forest Plantation in Kapuas district in Central Kalimantan, in January 2021. By Aidenvironment.